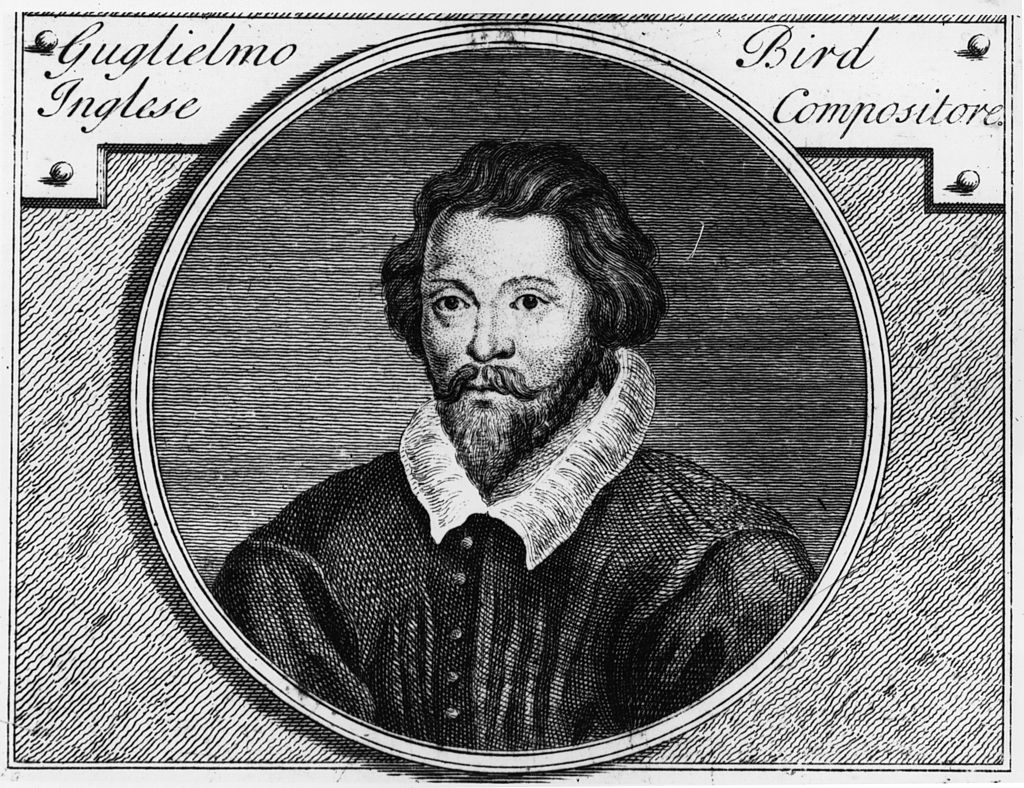

This month marks four centuries since the death of William Byrd, the great Elizabethan composer, and one of the most remarkable composers of the Renaissance. He was a Catholic, certainly from the 1570s, who contrived to weather the religious persecution of the era while working at the heart of Elizabeth I’s court; it may have been the Queen’s favour that saved him from persecution. Indeed the serenity of his motets, composed for performance in recusant houses where both priest and congregation were at risk of death for their Catholic worship, must have constituted a kind of spiritual refuge from the threats all around them.

The Masses he set would have been sung in and for a congregation that could be infiltrated by spies and informers, and they sustained and elevated that worship. One memorable gathering Byrd attended at a country house in 1586 was in the company of Father Henry Garnet (later executed for his part in the Gunpowder Plot) and the martyr priest-poet Father Robert Southwell. Of course, Byrd composed many lovely pieces for Anglican worship too, but many of his motets can best be understood as him interpreting biblical and liturgical texts in a contemporary context and writing laments and petitions on behalf of the persecuted Catholic community.

Byrd’s work is immortal, but it is also a product of a particular time and place. He is a reminder of the potential of art and music in particular to provide an internal place of refuge from persecution and tribulation. The beauty of worship he provided is an eternal riposte to the savagery of a system that killed many priests he knew for the cause of the Faith. We who listen to Byrd’s music in peace and without fear should remind ourselves of the dark days for which it was written, and be thankful for the genius that could respond to adversity with compositions of abiding beauty that can increase our own faith in very different times.

This month marks four centuries since the death of William Byrd, the great Elizabethan composer, and one of the most remarkable composers of the Renaissance. He was a Catholic, certainly from the 1570s, who contrived to weather the religious persecution of the era while working at the heart of Elizabeth I’s court; it may have been the Queen’s favour that saved him from persecution. Indeed the serenity of his motets, composed for performance in recusant houses where both priest and congregation were at risk of death for their Catholic worship, must have constituted a kind of spiritual refuge from the threats all around them.

The Masses he set would have been sung in and for a congregation that could be infiltrated by spies and informers, and they sustained and elevated that worship. One memorable gathering Byrd attended at a country house in 1586 was in the company of Father Henry Garnet (later executed for his part in the Gunpowder Plot) and the martyr priest-poet Father Robert Southwell. Of course, Byrd composed many lovely pieces for Anglican worship too, but many of his motets can best be understood as him interpreting biblical and liturgical texts in a contemporary context and writing laments and petitions on behalf of the persecuted Catholic community.

Byrd’s work is immortal, but it is also a product of a particular time and place. He is a reminder of the potential of art and music in particular to provide an internal place of refuge from persecution and tribulation. The beauty of worship he provided is an eternal riposte to the savagery of a system that killed many priests he knew for the cause of the Faith. We who listen to Byrd’s music in peace and without fear should remind ourselves of the dark days for which it was written, and be thankful for the genius that could respond to adversity with compositions of abiding beauty that can increase our own faith in very different times.