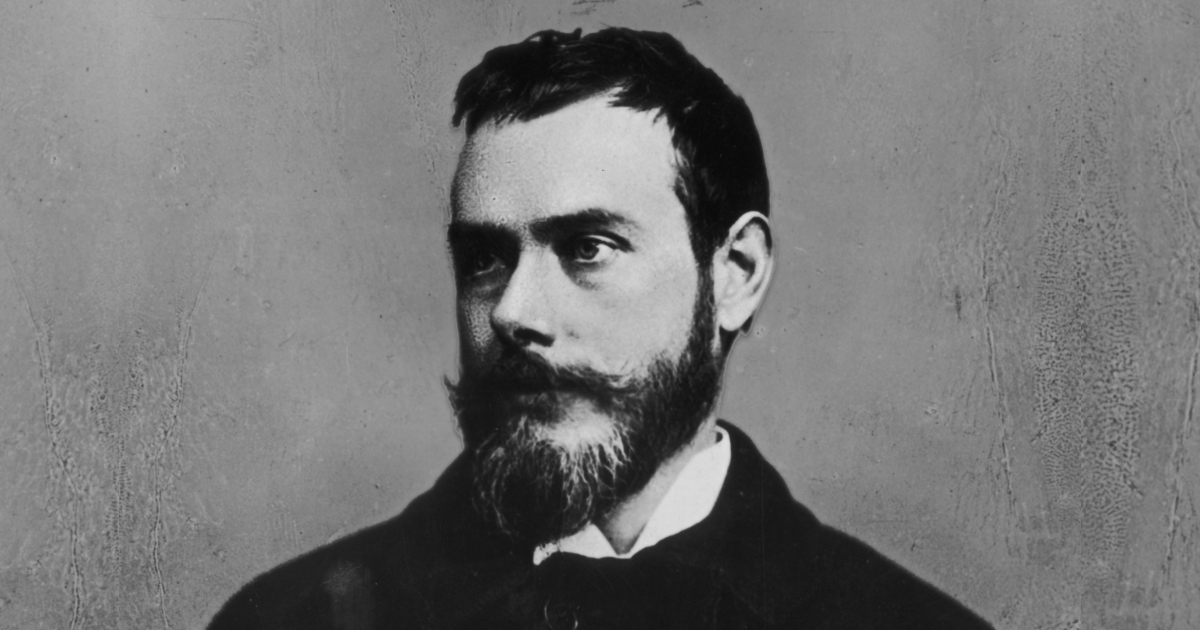

In early 1945, a contributor to the Catholic Herald suggested that the city of Coventry could be named for a medieval Catholic religious house. Professor J. R. R. Tolkien, reading this, and having done his research, wrote in to correct the record and share his thoughts on Catholicism's place in the study of Anglo-Saxon etymology for the 23 February, 1945 issue.

SIR – With reference to the letter of "H.D." on the subject of Coventry, I am at a loss to know how the etymology of any place-name can be pursued "in keeping with Catholic tradition", except by seeking the truth without bias, whether one ends up in a convent or not. But, the consequences of St. Osburg's convent is in any case in no way concerned.

The derivation of the name Oxford from an ancient drovers' ford in the West of the city casts no doubt on the importance of the University of Oxford in the Middle Ages. "H. D." would possibly feel happier if Oxford was called Doncaster, but the history of place names is seldom so simple.

One thing at least has been made clear by the critical study of place names: guessing etymologies from the modern forms is useless. The accidental similarity of covent in Coventry to convent, or to the older form covent (which does survive in Covent Garden), is a good illustration. For this name appears already in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in the form Cofan-treo; whereas the word convent does not appear in English until after A.D. 1200. Its earliest recorded form is Kunvent (i.e. cuvent), "assembly," and though it was frequently applied to that meaning: the application to buildings is modern, and still more recent is the limitation to the houses of religious women.

The Anglo-Saxon word for religious house was mynster and this is, of course, a frequent element on English place names; but most of the names of places where great religious houses later grew up were far older than the religious foundation and so do not refer to it, whether it be Abingdon or Ramsey or Glastonbury, to choose some of the most notable. The case of Malmesbury, which blends the name of its seventh-century Irish founder, Maildub, with that of its most famous abbot, St. Aldhelm, is as rare as it is curious.

The settlement and naming of the Midlands lies far back in English history, and in the main preceded the conversion of the Angles. Indeed, the giving of names often preceded the formulation of the "places", that is of the villages and towns, and so originally denoted isolated swellings, boundary-marks, and local features, near which communities were later formed. Though many old names remain obscure, there is in the case of Coventry no room for reasonable doubt.

The Anglo-Saxon name means "Cofa's tree". It may be observed that a very similar name occurs not far away to the south-east in Daventry. In this case also the earliest spellings point to Dafan-treo, "Dafa's tree", and the fortunate absence of any modern word davent has prevented guess-work.

In Cofa and Dafa we have specimens of an ancient type of English personal name: a simple stem, unlike the more "aristocratic" double-barrelled names familiar in later history, such as Ead-weard or Æthel-red.

But names of the latter type are also found combined with "tree", as, for instance, in Austrey (another Warwickshire place-name) which has suffered more from the wear and tear of time and appears to go back to Eadwulfes treo or "Eadwulf's tree".

Compare also Oswestry and Allestree (Æthelheard's tree). The name Cofa appears in other place-names in other parts, Covington, Covenham, and Cobham: but these names are the only records that these long-forgotten "coves," these farmer-settlers, have left on the pages of history to-day.

Interest in place names is almost universal, but it would appear that much less widespread is the knowledge of how much work has been done in this field in recent years, especially by the late Sir Allen Mawer, and by Professor Stenton of Reading, and by Swedish scholar Ellert Ekwell, to name only the most eminent.

There is an English Place-Name Society, and its volumes still appear fairly regularly. Most public libraries are members and subscribers and possess its publications, amongst them the Gulston Library, Coventry if it is not destroyed. I refer any of your readers to Volume x (Northamptonshire for Daventry), volume xiii (Warwickshire), and volume i (i) (Introduction especially chapter iii, on the English Element): and also to Stenton's great work Anglo-Saxon England, which appeared in 1943.

This article originally appeared in the 23 February, 1945 issue of the Catholic Herald. To subscribe to our award-winning, thought-provoking magazine and have independent and high-calibre counter-cultural Catholic journalism delivered to your door anywhere in the world click here.

<em>In early 1945, a contributor to the Catholic Herald suggested that the city of Coventry could be named for a medieval Catholic religious house. Professor J. R. R. Tolkien, reading this, and having done his research, wrote in to correct the record and share his thoughts on Catholicism's place in the study of Anglo-Saxon etymology for the 23 February, 1945 issue.</em>

SIR – With reference to the letter of "H.D." on the subject of <em>Coventry</em>, I am at a loss to know how the etymology of any place-name can be pursued "in keeping with Catholic tradition", except by seeking the truth without bias, whether one ends up in a convent or not. But, the consequences of St. Osburg's convent is in any case in no way concerned.

The derivation of the name <em>Oxford</em> from an ancient drovers' ford in the West of the city casts no doubt on the importance of the University of Oxford in the Middle Ages. "H. D." would possibly feel happier if Oxford was called Doncaster, but the history of place names is seldom so simple.

One thing at least has been made clear by the critical study of place names: guessing etymologies from the modern forms is useless. The accidental similarity of <em>covent</em> in Coventry to <em>convent</em>, or to the older form <em>covent</em> (which does survive in Covent Garden), is a good illustration. For this name appears already in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in the form <em>Cofan-treo</em>; whereas the word convent does not appear in English until after A.D. 1200. Its earliest recorded form is <em>Kunvent</em> (i.e. <em>cuvent</em>), "assembly," and though it was frequently applied to that meaning: the application to buildings is modern, and still more recent is the limitation to the houses of religious women.

The Anglo-Saxon word for religious house was <em>mynster</em> and this is, of course, a frequent element on English place names; but most of the names of places where great religious houses later grew up were far older than the religious foundation and so do not refer to it, whether it be Abingdon or Ramsey or Glastonbury, to choose some of the most notable. The case of <em>Malmesbury</em>, which blends the name of its seventh-century Irish founder, Maildub, with that of its most famous abbot, St. Aldhelm, is as rare as it is curious.

The settlement and naming of the Midlands lies far back in English history, and in the main preceded the conversion of the Angles. Indeed, the giving of names often preceded the formulation of the "places", that is of the villages and towns, and so originally denoted isolated swellings, boundary-marks, and local features, near which communities were later formed. Though many old names remain obscure, there is in the case of Coventry no room for reasonable doubt.

The Anglo-Saxon name means "Cofa's tree". It may be observed that a very similar name occurs not far away to the south-east in <em>Daventry</em>. In this case also the earliest spellings point to <em>Dafan-treo</em>, "Dafa's tree", and the fortunate absence of any modern word <em>davent</em> has prevented guess-work.

In <em>Cofa</em> and <em>Dafa</em> we have specimens of an ancient type of English personal name: a simple stem, unlike the more "aristocratic" double-barrelled names familiar in later history, such as <em>Ead-weard </em>or <em>Æthel-red</em>.

But names of the latter type are also found combined with "tree", as, for instance, in <em>Austrey</em> (another Warwickshire place-name) which has suffered more from the wear and tear of time and appears to go back to <em>Eadwulfes treo </em>or "Eadwulf's tree".

Compare also <em>Oswestry</em> and <em>Allestree</em> (Æthelheard's tree). The name Cofa appears in other place-names in other parts, Covington, Covenham, and Cobham: but these names are the only records that these long-forgotten "coves," these farmer-settlers, have left on the pages of history to-day.

Interest in place names is almost universal, but it would appear that much less widespread is the knowledge of how much work has been done in this field in recent years, especially by the late Sir Allen Mawer, and by Professor Stenton of Reading, and by Swedish scholar Ellert Ekwell, to name only the most eminent.

There is an <em>English Place-Name Society</em>, and its volumes still appear fairly regularly. Most public libraries are members and subscribers and possess its publications, amongst them the Gulston Library, Coventry if it is not destroyed. I refer any of your readers to Volume x (Northamptonshire for Daventry), volume xiii (Warwickshire), and volume i (i) (Introduction especially chapter iii, on the English Element): and also to Stenton's great work Anglo-Saxon England, which appeared in 1943.

<strong><strong>This article originally appeared in the 23 February, 1945 issue of the <em>Catholic Herald</em>. To subscribe to our award-winning, thought-provoking magazine and have independent and high-calibre counter-cultural Catholic journalism delivered to your door anywhere in the world click</strong> <a href="https://catholicherald.co.uk/easter-24/?swcfpc=1"><mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color">here</mark></a>.</strong>