JD Vance is not a big fan of the political Left, despite his humble background. In the view of the Catholic politician that everyone is now talking about after Donald Trump nominated Vance as his running mate for the 2024 US presidential election, the political Left’s approach to poor, working-class communities like the one Vance grew up in is, in his words, “like sympathy for a zoo animal, and I have no use for it”.

Vance’s attempts to understand the self-destructive behavioural patterns that he witnessed in such communities have partly been informed by his study of French Catholic philosopher René Girard (1923-2015), to whose work Vance was introduced by billionaire Silicon Valley entrepreneur Peter Thiel. Vance has credited this exposure to Girard as a major impetus for his conversion to Catholicism.

RELATED: What are we to make of JD Vance, especially his turn to Catholicism?

Girard is best known for his “mimetic theory", which is nothing less than a full-scale attack on the Enlightenment’s core understanding of human beings as free, autonomous individuals capable of making rational decisions. For Girard it is mimetic desire, not reason, that drives our decision making, whereby far from human desire working independently and being entirely subjective, it is derived from the desires of others and hence is mainly responsible for the human condition’s capacity to believe in lies.

This mimesis applies across the whole spectrum of human experience – whether it be our political opinions or aesthetic tastes.

Oscar Wilde understood it when he once commented how “most people are other people". He explained: "Their thoughts are someone else’s opinion, their life a mimicry, their passions a quotation.”

Mimeticbehaviour acts in the manner of a triangular relationship between the subject, the object and a third party (the person or group whose desires are imitated), whereby the subject is pulled towards an object, via the third party, in the belief that the gaining of the object will lead to a transformation of the subject. But if the mimetic desire is frustrated then a sense of deep, existential despair is experienced by the subject, which is why mimetic behaviour leads to violence.

According to Girard, pre-Christian societies used the “scapegoat mechanism” to overcome the violence that is engendered in society by mimeticdesire being thwarted. Girard’s ideas about mimetic desire and its connection with the “scape goat” mechanism hit home with Vance because of his experience of social media and how it "captured so well the psychology of my generation, especially its most privileged inhabitants" as everyone sought someone to blame.

“Mired in the swamp of social media, we identified a scapegoat and digitally punched,” Vance comments. “We were keyboard warriors, uploading on people via Facebook and Twitter, blind to our own problems. We fought over jobs we didn’t actually want while pretending we didn’t fight for them at all. And the end result for me, at least, was that I had lost the language of virtue."

He concludes: "This all had to change. It was time to stop scapegoating and focus on what I could do to improve things.”

In pre-Christian communities beset by violence, an innocent victim would be identified for sacrifice; the sacrifice of that innocent victim ultimately leading to a cathartic experience and a restoration of peace.

Through the Christian revelation, however, of the innocence of the victim, starting with Christ, Christianity brought about an end to the “scapegoat mechanism”.

The Gospels reveal that the "guilt" borne by Christ was actually the psychological projection by the crowd. Christianity is, therefore, argued Girard, the religion to end all religions.

When Christ said: “Think not that I am come to send peace on earth: I came not to send peace, but a sword,” he did so because he knew that an ultimate consequence of the ending of the “scapegoat mechanism” would be increased levels of violence. This was because, despite Christianity’s ending of the “scapegoat mechanism”, mankind’s stubborn inclination to persecute would remain.

So though Christ showed that patterns of violence can only be truly defeated through the exercise of love, Girard points out the intervening problem of how love often masquerades as hypocrisy. This helps explain why so many nowadays persecute in the name of the victim, as opposed to the victim themselves seeking a more justified retribution.

Our desire to persecute remains as strong as ever.

Girard believed that the reason the world has not already collapsed, despite the undercurrents of continuing extreme violence, is because in the modern world we have discovered new ways of channelling that violence: most especially through capitalism and the law.

Capitalism, Girard argued, is a magnet for criminal instinct and a seething mass of violent energy. Capitalist activity is only rendered peaceful because of the activity of the law which brings about peace between disputing parties through negotiation, rather than through catharsis.

Girard urges us not to be fooled by capitalist claims to altruism and “corporate responsibility”. He points out that global trade – especially at the intersection between trade and law – can go very quickly from being a conduit for peace and well-being to being a catalyst for war. By the time Girard died in 2015, he had become especially preoccupied by the prospect of a war, triggered between China and the USA.

Girard believed that the new “church” of science and reason, and held aloft by modernism, actually threatens to drive us all away from science and reason into a new dark age.

Mankind’s ability to connect with truth again, Girard reasoned, will only be possible if it ends its fetishisation of science and learns how to love. Without love there can be no truth, and it will only be through the exercise of love that the chain of violence created by mimetic desire will be broken.

Because of all of this, in Girard’s view, we live in apocalyptic times, and the only viable option now is to withdraw from the world and develop our capacity for love.

If asked to identify specific ways in which Girard’s thought might impact on a Vance vice presidency – and on a possible presidency later on – I would guess as follows.

First, the enablement of localisation and decentralisation within the USA, in order to help communities, such as the ones Vance grew up in, build resilience, in what is likely to be an increasingly chaotic world. It is interesting to note the crypto currency Bitcoin surged in value immediately after the announcement of Vance’s nomination for the vice presidency.

Second, a prioritisation of US defence spending away from Europe to focus on Southeast Asia, in order to secure US markets in the face of increasing Chinese power.

Third, policies that mitigate the negative effects of global capitalism, including the use of tariffs, in order to build American societal resilience in the face of increasing Chinese competitiveness.

Finally, Vance is unlikely to be sympathetic to victim-based, human rights demands, his energies being focussed instead on how to best break the cycle of mimetic violence through the establishment of truly resilient communities.

Communities, that is, that speak the language of love, the language of Christ.

RELATED: Muddled end to Joe Biden’s re-election campaign highlights dysfunction plaguing US politics

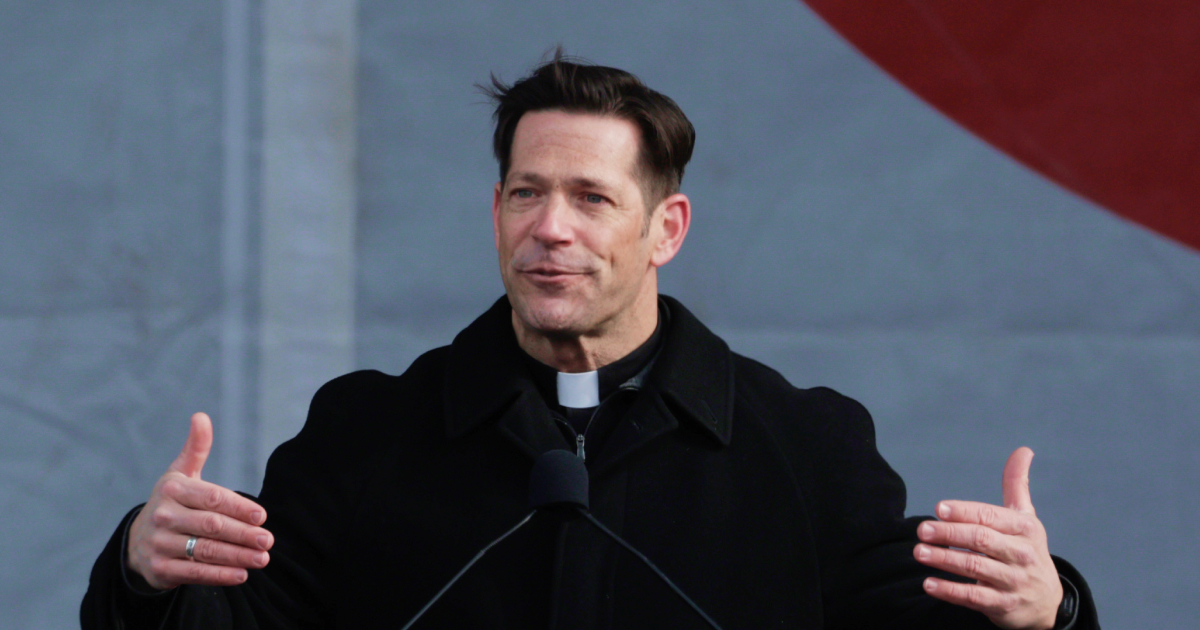

Photo: Republican vice presidential candidate, US Sen. J.D. Vance (R-OH) speaks during a fundraising event at Discovery World in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA, 17 July 2024. The fundraiser was Vance's first since being picked to be the running mate for the Republican's presidential candidate, former US President Donald Trump. (Photo by Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images.)

Mark Jenkins is an independent writer, philosopher and consultant with a focus on the intersection between geopolitics and religion in the twenty first century.

JD Vance is not a big fan of the political Left, despite his humble background. In the view of the Catholic politician that everyone is now talking about after Donald Trump nominated Vance as his running mate for the 2024 US presidential election, the political Left’s approach to poor, working-class communities like the one Vance grew up in is, in his words, “like sympathy for a zoo animal, and I have no use for it”.

Vance’s attempts to understand the self-destructive behavioural patterns that he witnessed in such communities have partly been informed by his study of French Catholic philosopher René Girard (1923-2015), to whose work Vance was introduced by billionaire Silicon Valley entrepreneur Peter Thiel. Vance has credited this exposure to Girard as a major impetus for his conversion to Catholicism.<br><br><strong>RELATED: <a href="https://catholicherald.co.uk/what-are-we-to-make-of-jd-vance-including-his-turn-to-catholicism/?swcfpc=1"><mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color">What are we to make of JD Vance, especially his turn to Catholicism?</mark></a></strong>

Girard is best known for his “mimetic theory", which is nothing less than a full-scale attack on the Enlightenment’s core understanding of human beings as free, autonomous individuals capable of making rational decisions. For Girard it is mimetic desire, not reason, that drives our decision making, whereby far from human desire working independently and being entirely subjective, it is derived from the desires of others and hence is mainly responsible for the human condition’s capacity to believe in lies.

This <em>mimesis </em>applies across the whole spectrum of human experience – whether it be our political opinions or aesthetic tastes.

Oscar Wilde understood it when he once commented how “most people are other people". He explained: "Their thoughts are someone else’s opinion, their life a mimicry, their passions a quotation.”

Mimetic<em> </em>behaviour acts in the manner of a triangular relationship between the subject, the object and a third party (the person or group whose desires are imitated), whereby the subject is pulled towards an object, via the third party, in the belief that the gaining of the object will lead to a transformation of the subject. But if the mimetic desire is frustrated then a sense of deep, existential despair is experienced by the subject, which is why mimetic behaviour leads to violence.

According to Girard, pre-Christian societies used the “scapegoat mechanism” to overcome the violence that is engendered in society by mimetic<em> </em>desire being thwarted. Girard’s ideas about mimetic desire and its connection with the “scape goat” mechanism hit home with Vance because of his experience of social media and how it "captured so well the psychology of my generation, especially its most privileged inhabitants" as everyone sought someone to blame.

“Mired in the swamp of social media, we identified a scapegoat and digitally punched,” Vance comments. “We were keyboard warriors, uploading on people via Facebook and Twitter, blind to our own problems. We fought over jobs we didn’t actually want while pretending we didn’t fight for them at all. And the end result for me, at least, was that I had lost the language of virtue."

He concludes: "This all had to change. It was time to stop scapegoating and focus on what I could do to improve things.”

In pre-Christian communities beset by violence, an innocent victim would be identified for sacrifice; the sacrifice of that innocent victim ultimately leading to a cathartic experience and a restoration of peace.

Through the Christian revelation, however, of the innocence of the victim, starting with Christ, Christianity brought about an end to the “scapegoat mechanism”.

The Gospels reveal that the "guilt" borne by Christ was actually the psychological projection by the crowd. Christianity is, therefore, argued Girard, the religion to end all religions.

When Christ said: “Think not that I am come to send peace on earth: I came not to send peace, but a sword,” he did so because he knew that an ultimate consequence of the ending of the “scapegoat mechanism” would be increased levels of violence. This was because, despite Christianity’s ending of the “scapegoat mechanism”, mankind’s stubborn inclination to persecute would remain.

So though Christ showed that patterns of violence can only be truly defeated through the exercise of love, Girard points out the intervening problem of how love often masquerades as hypocrisy. This helps explain why so many nowadays persecute in the name of the victim, as opposed to the victim themselves seeking a more justified retribution.

Our desire to persecute remains as strong as ever.

Girard believed that the reason the world has not already collapsed, despite the undercurrents of continuing extreme violence, is because in the modern world we have discovered new ways of channelling that violence: most especially through capitalism and the law.

Capitalism, Girard argued, is a magnet for criminal instinct and a seething mass of violent energy. Capitalist activity is only rendered peaceful because of the activity of the law which brings about peace between disputing parties through negotiation, rather than through <em>catharsis</em>.

Girard urges us not to be fooled by capitalist claims to altruism and “corporate responsibility”. He points out that global trade – especially at the intersection between trade and law – can go very quickly from being a conduit for peace and well-being to being a catalyst for war. By the time Girard died in 2015, he had become especially preoccupied by the prospect of a war, triggered between China and the USA.

Girard believed that the new “church” of science and reason, and held aloft by modernism, actually threatens to drive us all away from science and reason into a new dark age.

Mankind’s ability to connect with truth again, Girard reasoned, will only be possible if it ends its fetishisation of science and learns how to love. Without love there can be no truth, and it will only be through the exercise of love that the chain of violence created by mimetic desire will be broken.

Because of all of this, in Girard’s view, we live in apocalyptic times, and the only viable option now is to withdraw from the world and develop our capacity for love.

If asked to identify specific ways in which Girard’s thought might impact on a Vance vice presidency – and on a possible presidency later on – I would guess as follows.

First, the enablement of localisation and decentralisation within the USA, in order to help communities, such as the ones Vance grew up in, build resilience, in what is likely to be an increasingly chaotic world. It is interesting to note the crypto currency Bitcoin surged in value immediately after the announcement of Vance’s nomination for the vice presidency.

Second, a prioritisation of US defence spending away from Europe to focus on Southeast Asia, in order to secure US markets in the face of increasing Chinese power.

Third, policies that mitigate the negative effects of global capitalism, including the use of tariffs, in order to build American societal resilience in the face of increasing Chinese competitiveness.

Finally, Vance is unlikely to be sympathetic to victim-based, human rights demands, his energies being focussed instead on how to best break the cycle of mimetic violence through the establishment of truly resilient communities.

Communities, that is, that speak the language of love, the language of Christ. <br><br><strong>RELATED: <a href="https://catholicherald.co.uk/the-muddled-end-to-joe-bidens-campaign-highlights-problems-plaguing-us-politics/?swcfpc=1"><mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color">Muddled end to Joe Biden’s re-election campaign highlights dysfunction plaguing US politics</mark></a></strong>

<em>Photo: Republican vice presidential candidate, US Sen. J.D. Vance (R-OH) speaks during a fundraising event at Discovery World in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA, 17 July 2024. The fundraiser was Vance's first since being picked to be the running mate for the Republican's presidential candidate, former US President Donald Trump. (Photo by Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images.)</em> <br><br><em>Mark Jenkins is an independent writer, philosopher and consultant with a focus on the intersection between geopolitics and religion in the twenty first century.</em>