Where are we, four years on? None of the promises that were repeated so loudly during 2020 and 2021 have come to fruition: neither the New Normal – a new age of safety and perfect management of the hazards that beset humans – nor the longed-for “back to normal”.

The Covid Era has been followed, instead, by a plethora of crises. All of us are dealing with higher prices and many of us have been pushed into a lower standard of living. The news suggests that intractable conflicts in far-away places may yet come to our doors. The tax take is of World War II proportions, but public services are being cut ever further. Potholes and roadworks are everywhere; it sometimes seems as if the fabric of modern Britain is disintegrating.

Underlying the all-too-perceptible economic, social and political crises is a spiritual and psychological crisis that has been long in the making. It's linked to the breakdown of institutional religion, to the passing of the old and the space that opens up before the new comes into being. But if we pay attention to the spiritual foundations of this crisis – which are intimately linked to the psychological – it presents a meaning-making opportunity beyond compare.

For now, though, it looks as if the government has taken the population's compliance with the Covid restrictions as license to introduce more and more rules governing everyday life. The most obvious are the restrictions on the movement of vehicles in towns and cities which levy charges on those who can least afford them. Behind the scenes, unnamed figures are about to agree a raft of new measures to give the World Health Organisation new powers in the event of health or climate-related crises. And all the while there's the creep-creep of digital incursion into our lives, from the police's use of facial recognition to <a href="https://www.mirror.co.uk/money/dwp-bank-snooping-powers-could-32717747"><mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color">government plans to surveil our bank accounts</mark></a>.

On the social level, cherished values and longstanding identities are up for grabs. Fixed poles of human existence, such as difference between men and women, are suddenly on the move. Any feelings of excitement that might accompany rapid social change if it arose organically are quashed by the culture of suppression that accompanies them. Major institutions cancel talks by writers and thinkers. People lose their jobs for expressing an “incorrect” opinion. New laws, such as <a href="https://catholicherald.co.uk/where-is-churchs-outcry-on-nightmarish-nature-of-scotlands-new-thought-crime-law/"><mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color">Scotland's new Hate Crime and Public Order Act</mark></a>, criminalise the making of certain statements about religion, sex or gender.

Even without the heavy hand of the law, open discussion is difficult since so much of public debate now consists of binary oppositions and tribal affiliations, with name-calling and crude slurring tactics taking the place of reasoned discussion.

For many, all this is as hard to understand as it is impossible to ignore. People are getting on with their lives as best they can, expressing their bemusement at what's going on around them with phrases such as “it's a funny time”. The expression of a vague hope that things will somehow resolve themselves tends to follow this brief acknowledgement; there's little sense that any conscious decision-making or purposeful action is called for.

But here's the thing. The period of ongoing crisis and uncertainty that began in 2020 was not an exception or an anomaly, but an expression of Western culture. It's an expression of a direction we've been going in for some time as a society based on scientific materialism in which we increasingly rely on the industrial, the global and the technological to meet our needs.

In the wake of the Covid crisis, we're heading faster than ever, towards a future which – if the promises are to be believed – will involve less suffering and more convenience, less effort and more gratification. It will also involve more automation and less agency, more machine and less human. Ultimately the broad spectrum of developments that fall under the heading of “<a href="https://catholicherald.co.uk/the-cult-of-sexual-transitioning-and-disembodied-transhumanism-is-a-misguided-quest-for-eternity-in-denial-of-the-incarnation/"><mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color">transhumanism</mark></a>” heralds the triumph of the material over the spiritual.

Almost fifteen years ago, I got curious about how others were responding to this time of transition and went in search of individuals and communities who, against a backdrop of growing secularisation, were looking for ways of believing and belonging. Out of a large territory of varied beliefs, I chose three traditions which arguably most represented the alternative faithscape of contemporary Britain: contemplative Christianity, neo-paganism and mystical Islam.

Research into the first of these took me to Holy Trinity, a start-up Benedictine monastery composed of three nuns and a dog founded by the late Dame Catherine Wybourne after her painful break from Stanbrook Abbey. I interviewed a hermit of four decades' standing in the Romanesque complex he'd built on top of a Northumberland hill. Brother Harold Palmer denied the life he was living was solitary because he was perpetually “in communion with the angels and the saints”.

The courage and creativity of these two people, like that of others I met researching <em>The Secret Life of God</em>, was extraordinary. Instead of following the default trend of their society, they were forging a new path prompted by an inner life of the spirit. They were attempting to bring the religious impulse into a new physical form, expressed in buildings, relationships and a particular way of life. Looking back, it seems to me they were responding, in a pro-active and positive way, to an earlier stage of our current crisis.

Crisis. It's a word I'm using a lot and, despite having consulted a thesaurus, I can't find another as pertinent. Maybe that's to do with the etymology of the term which, from the Latinised form of its Greek root, means “decisive point in a disease or situation, a turning point which leads to either recovery or death”. Even more helpfully, its Proto-Indo-European root “krei”, meaning “to sieve” or “distinguish”, points to the idea of making a decision as a result of a trial.

So here we are, in the Britain of the 2020s, in a crisis that won't go away of its own accord. The outward signs are the tough stuff – the things that aren't working, the authorities' attempts at top-down control, and the onward march of a new technology we've barely begun to understand.

To access this opportunity, we have to get beyond our <em>crisis of avoidance</em>. We need to start looking at the world that's grown up around us with realistic eyes, face the harsh truths it presents us with, and begin a process of inquiry and reflection. Readiness to question and explore will lead us to the discernment buried in the word “crisis” – and ultimately to clarity about which paths to reject and which to choose.

This is how spiritual and social evolution comes about. We don't need to be as overtly pioneering as Dame Catherine and Brother Harold; we just have to be prepared to venture beyond established boundaries in our own lives. It's a journey that could make heroes of all of us.

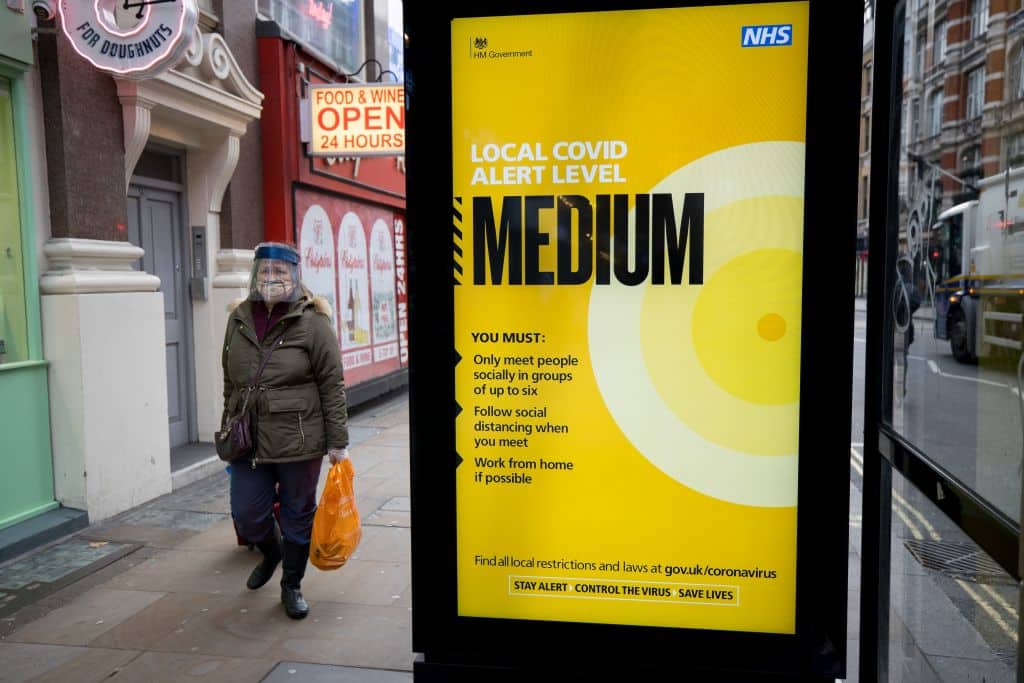

<em>Alex Klaushofer is a journalist and the author of '</em><a href="https://www.amazon.co.uk/Secret-Life-God-journey-through/dp/099332360X/ref=sr_1_6?crid=3KJMA3B4B0WE1&dib=eyJ2IjoiMSJ9.-yN19U3SY4-t2fdDGoDJIH6pt12qDLR4ql5591grQzbG_-MtLcdt5mJPCStxem6y031dMZFsstu-KH8kqAqYt-L_8FIZ8W7G52DNVhST1gw.tI3y6BAx4bivi5hk9GmB8oi1UeyTnY4Zrujlf2BFsaQ&dib_tag=se&keywords=alex+klaushofer&qid=1715180593&sprefix=alex+klaushofer,aps,75&sr=8-6"><em><mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color">The Secret Life of God: A journey through Britain</mark></em></a><em>'. She writes about the changing times </em><a href="https://alexklaushofer.substack.com/"><em><mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color">on Substack at Ways of Seeing</mark></em></a><em>.</em><br><br><em>Photo: A pedestrian walks past a NHS sign displaying Covid-related guidelines at a bus-stop shelter in the West End of London, England, 14 October 2020. At the time, Prime Minister Boris Johnson said a new UK-wide lockdown would be a 'disaster' but refused to rule it out as some demanded another 'temporary shutdown to stop the spread' of Covid. (Photo by Tolga Akmen / AFP) (Photo by TOLGA AKMEN/AFP via Getty Images.)</em>