Her Royal Highness the Duchess of Kent, who died on 4 September aged 92, was the first senior member of the British royal family to convert to Catholicism since Princess Ena of Battenberg – a granddaughter of Queen Victoria through Princess Beatrice – married the Spanish Alonso XIII in 1906.

As his wife only became a Catholic 33 years after their wedding, the Duke of Kent retained his place in the line of succession, unaffected by the Royal Marriages Act of 1772. In 2001, their son Lord Nicholas Windsor also converted; their grandchildren Lord Downpatrick and Lady Marina Windsor followed in 2003 and 2008. This time round, then, on 16 September, the sacred rites of a royal funeral fell to the Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster.

How odd it was not to see the members of the Chapter of Westminster Abbey escorting the King and other members of the Royal Family to their seats, but rather the Chaplains of the Cathedral, in their grey-and-purple cappae. How strange, under the Duchess's coronet and cypher, to read the legend "Requiem Mass". How curious, almost to the point of disjuncture, to see the backs of familiar heads filling the front of a foreign nave – less foreign, at least, to the members of the House of Kent.

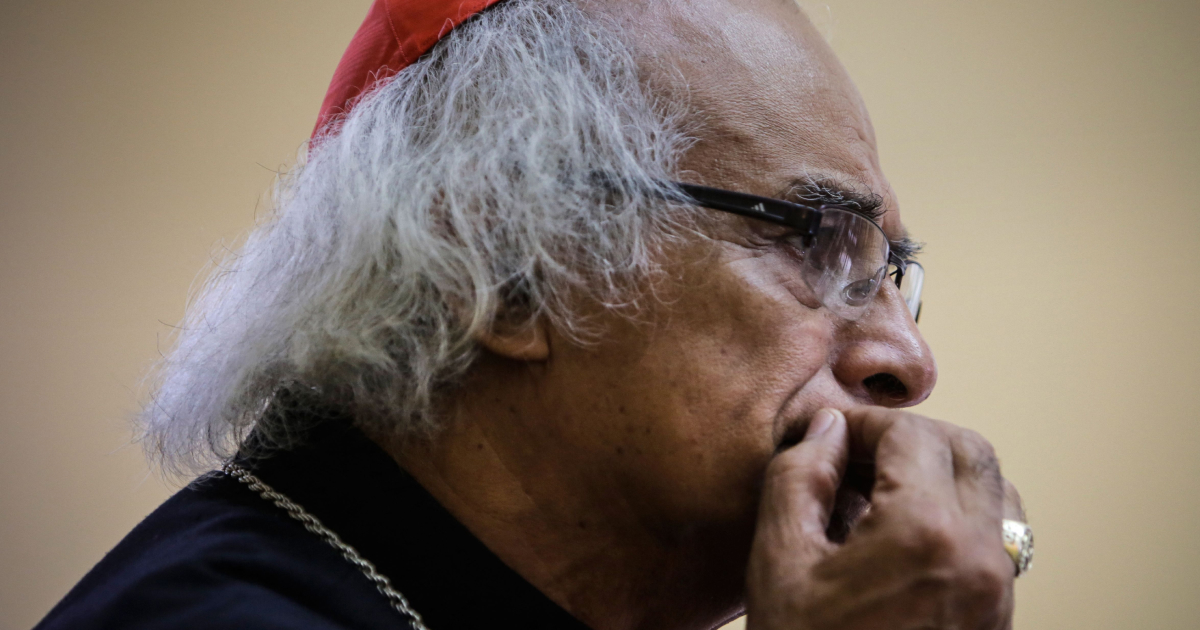

How historic, too, to see the paws of lions or passant guardant clutching a coffin on a precarious catafalque while Cardinal Nichols celebrated Mass at the high altar of his cathedral, accompanied by concelebrating clergy in very simple vestments. Some might think that it was a missed opportunity to showcase aesthetic prowess; others may well reflect that had the break with Rome not taken place then it would have simply been business as usual at Westminster Abbey, with no one any the wiser. Certainly the Dean of Windsor would have joined the procession, as he did, but not in the rochet and chimere of a Reformed prelate.

There are now few royal funerals to which the Pope sends messages, thanks to a paucity of crowned heads and a proliferation of Protestantism among those that remain. After the diplomatic niceties, however, Pope Leo opened his treasury of grace. "I readily associate myself with all those offering thanksgiving to Almighty God for the Duchess's legacy of Christian goodness," he wrote, through the apostolic nuncio, Archbishop Buendía.

"To all who mourn her loss, in the sure hope of the Resurrection, I willingly impart my apostolic blessing as a pledge of consolation and peace in the Risen Lord." That includes, presumably, the King, the Prince of Wales and young Prince George: the present and next two Supreme Governors of the Church of England. Less obliquely, the Pope included by name the Duchess's elderly, tottering widower, who, as the cortege made its way back to the west door, accompanied his wife out of church for the last time.

The first time was 64 years ago, at the end of another noteworthy ceremony: the first royal wedding to take place at York Minster since that of Edward III and Philippa of Hainault in 1328. In 1961 Princess Ena was there, as the by-then-exiled Queen Victoria Eugenie of Spain.

Katherine Worsley, the scion of a family of Yorkshire baronets, was charming, sparkling and witty. She became a perfect foil to her husband, two years her junior: a quieter, more reserved, soldier, later a field marshal, who had inherited his dukedom at the age of six when his father, Prince George, was killed on active service during the Second World War. Their wedding captured the hearts and minds of a nation; it even popularised the now-ubiquitous "Toccata in F" by Charles-Marie Widor, which the Minster organist, Francis Jackson, played afterwards. Their marriage, although not without its challenges, endured to the very end.

Those challenges included the loss of two children in the womb. Writing to the British Congress of Obstetrics in 1977, the Duchess emphasised how the gift of human life was God's. She went on to say that each birth was a miracle, and that those who worked to protect unborn children were to be applauded. It was an unusual but much needed royal intervention into the British abortion debate while many parliamentarians tried, and ultimately failed, to keep the limit to 20 weeks. Her own searing grief led to depression and withdrawal, which she sought to overcome, like so many before her, by reflecting on her faith.

She went on pilgrimage to Walsingham with Robert Runcie, the Archbishop of Canterbury, but the Church of England was beginning to tear itself apart over women's ordination and its internal uncertainties brought her into discussion with Bishop Gordon Wheeler of Leeds, himself a convert. Her journey led her on to Basil Hume, by then Archbishop of Westminster and a cardinal, but who had been Abbot of Ampleforth, only a few miles away from her ancestral home at Hovingham, in the North Riding. With the then-Queen's consent, he received her into the Church in 1994; after the funeral the family laid her wreath on his grave.

It was impossible not to admire the Duchess of Kent, for she was radiantly humane: partly because of her personal experience of pain, but also by natural temperament. She loved music and people: she sat and sang with dying children; she famously embraced a tearful Jana Novotná after she lost to Steffi Graf at Wimbledon in 1993. She was happy to touch and be touched, to hug and to heal.

When she was inadvertently embraced by another shopper in a large London store who had mistaken her for someone else, she allayed the poor woman's dawning mortification by asking after her health and parting with "It was lovely to meet you." Despite her rank she was gloriously unfussy – she preferred to be known as "Katharine Kent" and often had a twinkle in her eye.

She greeted nurses and soldiers like old friends; she went to Lourdes and took her turn with mop and bucket. She trained as a Samaritan, counselling those undergoing mental-health crises; she was patron of dozens of societies, a university chancellor, a regimental colonel and an honorary freeman of sundry City livery companies. Away from the glamour – and she could be exceedingly glamorous – she worked as a volunteer for the Passage, which supports homeless people in the heart of London.

She later quietly stepped out of the limelight after decades spent representing the Crown at home and abroad: she sang in choirs and taught music to children at a primary school in Hull, who simply knew her as "Mrs Kent". She appeared in public much less often as her health declined, although she could sometimes be seen in London, on the arm of the Duke, going to the hairdresser. For all the ups and downs that inevitably accrue to over six decades of marriage, their devotion to each other was as strong at the end as it had been at the beginning.

After the requiem, the Duchess of Kent's mortal remains were taken from Westminster Cathedral to Windsor, where they were laid to rest in the Royal Burial Ground at Frogmore: "entrusting her noble soul", as Pope Leo wrote, "to the mercy of our Heavenly Father".

Photo: the Duchess of Kent (image by Arcadia)

The Duchess of Kent, born 22 February 1933, died 4 September 2025. Serenhedd James is a former Editor of the Catholic Herald

This article appears in the October/November 2025 edition of the Catholic Herald. To subscribe to our thought-provoking magazine and have independent, high-calibre and counter-cultural Catholic journalism delivered to your door any where in the world click HERE.