I dare say that few British <em>Catholic Herald</em> readers are atheists. A number won’t vote Labour. But even some of those who do will recoil at the prospect of “the first atheist prime minister in British history”, as an interviewer described Sir Keir Starmer moving into 10 Downing Street later this year – as he seems almost certain to do.

But the facts of the matter, and their implications, turn out to be more complicated. For a start, the interviewer may have been wide of the mark. Sir Keir indeed replied, “No, I don’t”, when asked whether he believes in God. But that doesn’t necessarily set him up to be Britain’s first atheist prime minister.

According to Fr Mark Vickers, in his book <em>God in Number 10: The Personal Faith of the Prime Ministers, from Balfour to Blair</em>, Clement Attlee didn’t believe in God, either. “Believe in the ethics of Christianity,” he once said. “Can’t believe the mumbo-jumbo.”

Jim Callaghan, another Labour prime minister, may also have been an atheist. Neville Chamberlain, a Conservative one, once described himself as “a reverent agnostic”. Winston Churchill seems to have been a deist, or at least a believer in providence and destiny.

Indeed, the more one reads up on the matter, the more one comes to see that only a minority of Fr Vickers’s subjects were or are believing, practising Christians. Strikingly, few of them held office until the mid-1950s; Harold Macmillan being the first, and Theresa May the last.

An optimistic, ecumenical Catholic might see this development as evidence of politicians getting better rather than worse. A sceptical one would ask some searching questions. These might begin with one of the recent prime ministers that the Conservatives have provided: Boris Johnson.

Was Johnson Britain’s first Catholic prime minister? Baptised as a Catholic, confirmed as an Anglican, he seems to resemble David Cameron who once compared his faith to “Magic FM in the Chilterns, in that the signal comes and goes”. Though, more recently, Johnson declared that Christianity “makes a lot of sense to me”.

But, whatever he does or doesn’t believe, few would claim that Johnson’s premiership helped to build up the Kingdom of God on earth or even, a bit more modestly, left Britain a more Christian country, whatever that may mean, or was a model of Christian ethics, or indeed of ethics at all.

This points to a key question about faith and politics in Britain – namely, how much do a prime minister’s religious convictions matter? Shouldn’t we be more concerned with Sir Keir’s policies than his beliefs? Indeed, in modern, multicultural Britain, would a Christian prime minister perhaps be out of date?

We must all answer the question for ourselves, and mine would begin with another report about Sir Keir, this time from the <em>Jewish Chronicle </em>last year. “Our family treasures our Shabbat dinners, says Keir Starmer”, the headline on the article proclaimed.

It may not have been justified by the text in the article. Lady Starmer is Jewish, the family dines together on Friday evenings, it “did prayers each Friday over Zoom” during Covid and “Starmer and his family belong to London’s Liberal Jewish Synagogue”.

There was nothing in the story to confirm that prayers are said at these weekly family meals. But that is wide of the point, which is that, regardless of Sir Keir’s religious views, he has religious experience or, rather, a rubbing acquaintance with religious practice.

The same goes for his own modest background in Hurst Green, a commuter town in Surrey, where – as his latest biography by Tom Baldwin makes clear – his disabled mother was a regular at tender at St John’s Anglican church, which was, in the way of things, a centre of community as well as a place of worship.

His father, though a militant atheist, had a friendly relationship with the vicar and lent him the family’s rescue donkey for the Palm Sunday procession. So Starmer is at least familiar with Anglicanism as a source of mutual support and social cohesion.

This contact with Judaism, as well as Christianity, matters today in a way it wouldn’t have done when Attlee was prime minister. The Britain of 1945 was Christian culturally if not so religiously, for churchgoing was undergoing a long decline from its Victorian highpoint. Its ethics and worldview were grounded in Christianity.

Not so today: but it doesn’t follow that either religion, generally, or Christianity, specifically, have no place in the public square. Or that Sir Keir and his successors are likely to govern well without some kind of understanding of both.

Consider, by way of specific example, Labour’s exposure to charges of anti-Semitism. “I’m sure when [world leaders] go home, like me, pardon my French, [they say] ‘f **king Israel’ again,” Graham Jones, a Labour candidate, said recently.

He was promptly suspended. But while his remarks were undoubtedly anti-Zionist, were they actually anti-Semitic? There is room for doubt. Yet Labour’s anti-Semitism problem clearly hasn’t gone away: consider the suspension of its candidate during the recent Rochdale by-election. At the same time, the Conservatives have been accused of anti-Muslim hatred.

When is a remark anti-Semitic rather than anti-Zionist? What’s the difference between Islam, a great religion, and Islamism, a political ideology? The answer is inseparable from the idea of citizenship. Islamism rejects it – at least in many of its manifestations. The only legitimate ties that bind are those of faith – that’s to say of the Umma , the Muslim community. If that sounds strange, it shouldn’t do – at least to Catholics in Britain.

For we’re no strangers to the competing claims of faith and citizenship: consider the 16th-century claim that Catholics owed no obedience to a heretical monarch. Indeed, the tension between faith and state has been written into Christianity since before it existed.

“Whose portrait is this? Whose title? They said to him, ‘Caesar’s'.” Christ answered that what belongs to Caesar belongs to Caesar and what belongs to God belongs to God. Christians have argued ever since then about which is which. Maybe that’s the point.

Over two thousand years on and counting, citizenship is a core political matter for our age, and one that Sir Keir must prepare to negotiate. Can peace at home be insulated from wars abroad? How best can common values be built amid mass migration?

What relationship should we have with our European neighbours? Does diversity include a diversity of values? If so, how can Britain cohere? How can we include those set on excluding others? If we want equality, what equality? Of opportunity? Of outcome?

Family prayers on Friday over Zoom in the Starmer household may not provide the answers – any more than the shrine to Ganesh on Rishi Sunak’s desk, or Johnson’s musings on Christianity – “a superb ethical system and I would count myself as a kind of very, very bad Christian”.

But the experience may help to provide Sir Keir with a kind of map to steer by – with which to dip and swerve his way through the hazards of tomorrow’s Britain.

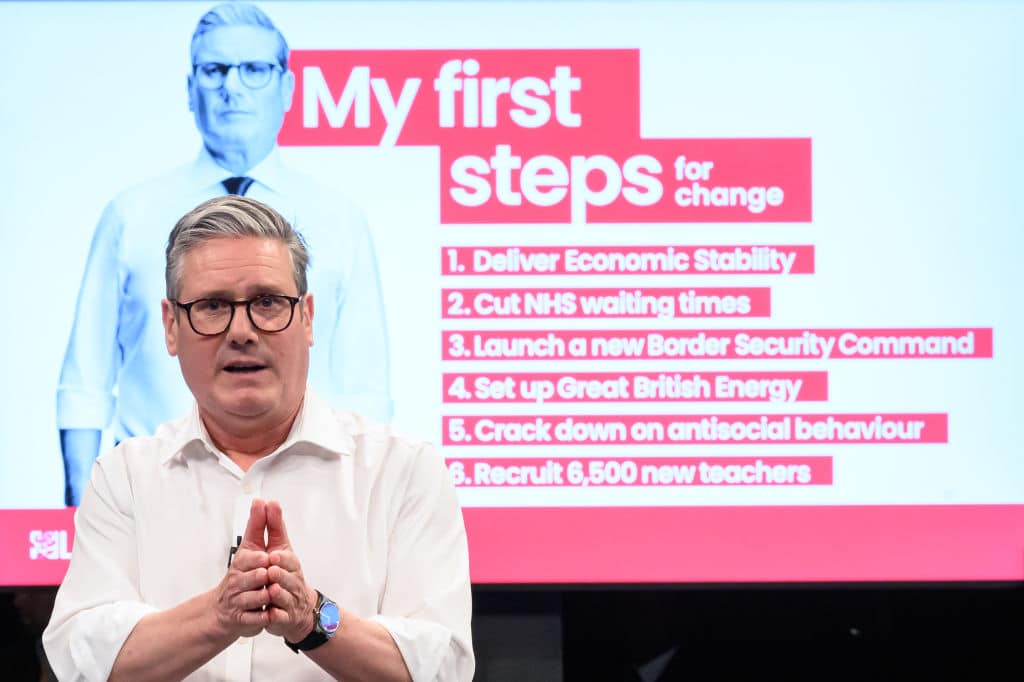

The lesson of Fr Vickers’s book may be that, for politicians, practising faith matters less than understanding it.<br><br><em>Photo: Labour Party Leader Keir Starmer stands in front of a screen displaying his six election pledges if Labour win the next General Election, Purfleet, England, 16 May 2024. (Photo by Leon Neal/Getty Images.)</em>

<em>Lord Goodman represented Wycombe between 2001 and 2010, and is a former editor of </em>ConservativeHome<em>.</em><br><br><strong><strong>This article originally appeared in the May 2024 issue of the <em>Catholic Herald</em>. To subscribe to our award-winning, thought-provoking magazine and have independent and high-calibre counter-cultural Catholic journalism delivered to your door anywhere in the world click</strong> <a href="https://catholicherald.co.uk/easter-24/?swcfpc=1"><mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color">here</mark></a>.</strong>