Among the narrative books of the New Testament, the Acts of the Apostles stands out as containing material claiming to be an eye-witness record of the events it reports. Many passages in the story of St Paul’s missionary journeys begin with the pronoun “we” and thus claim to be personal memories. The author of the work is a skilful writer. When narrating his own experiences he writes perfect Greek; when reporting speeches of others, such as St Peter, he is careful to include the semitisms of the original.

This means that there are marked differences between the style of the earlier chapters of the book, where we are being told the stories of Peter and Stephen, and that of the second part which narrates St Paul’s missionary journeys.

According to tradition the author of Acts was St Luke, the evangelist who wrote the third gospel – the “earlier work” mentioned in the introductory sentence of Acts. This tradition has been amply confirmed by recent stylometric studies. Luke now emerges as an even more versatile author. It is remarkable that the same man should be responsible both for first-person historical memories in Acts and also for the most memorable of the narratives of Jesus’s infancy – passages which are regarded even by some conservative scholars as symbolic or mythical. The human race is in Luke’s debt for some of the most universally beloved stories in religious literature.

The book of Acts is not at all as well known or loved as the infancy narratives. But it is a remarkable work in its own right. The leading characters, Peter and Paul, are sharply differentiated from each other. Neither is put on a pedestal in the same way as Jesus is in the gospels. We are left wondering what has happened, or is going to happen, to each of the pair. It is instructive to place side by side the narrative of Acts with the epistles that Paul wrote to the different Christian churches. Paul and Luke turn out to be very different people.

The most fascinating part of the Acts is contained in the later chapters where they narrate in the first person the shipwreck of Paul and his recovery on Malta. The story includes details that serve no missionary purpose but were clearly imprinted on the memory of the writer. “As we were making very heavy weather of it, the next day they began to jettison the cargo, and the third day they threw the ship’s gear overboard with their own hands. For a number of days both the sun and the stars were invisible and the storm raged unabated until at last we gave up all hope of surviving.”

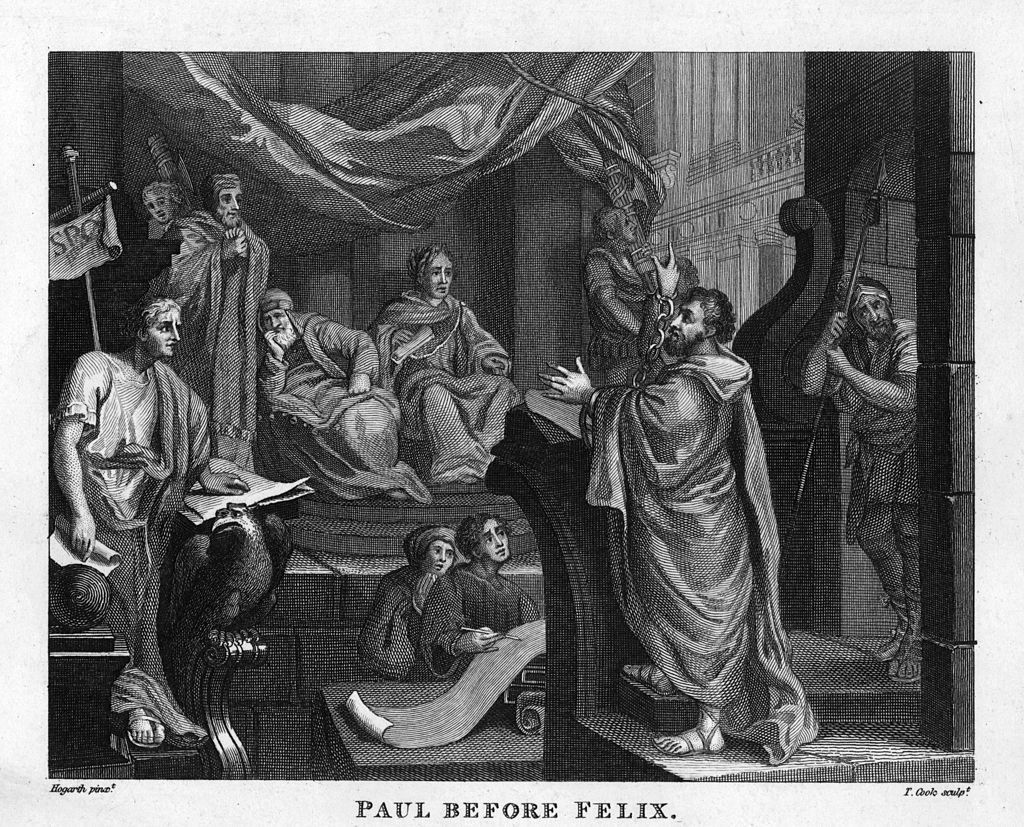

Writing the history of Paul’s journeys set a challenge to the narrator. Paul moved from province to province, each with its own governor or proconsul. If the story of his journeys is to maintain historical credibility, the identification of these personages must be reliable. Luke rises to this challenge remarkably effectively. Modern scholars confirm that he has identified correctly all the relevant officials.

Above all, the Acts is a book of reconciliation, bringing together the conflicting groups of Peter’s and Paul’s disciples. At its heart is the council of Jerusalem and the apostolic letter that Paul, Barnabas, Judas and Silas are to take to Antioch and elsewhere releasing Christians from the full obligations of Jewish law. Without the events narrated in Acts Christianity would never have flourished independently but would have remained a minor Jewish sect.

Among the narrative books of the New Testament, the Acts of the Apostles stands out as containing material claiming to be an eye-witness record of the events it reports. Many passages in the story of St Paul’s missionary journeys begin with the pronoun “we” and thus claim to be personal memories. The author of the work is a skilful writer. When narrating his own experiences he writes perfect Greek; when reporting speeches of others, such as St Peter, he is careful to include the semitisms of the original.

This means that there are marked differences between the style of the earlier chapters of the book, where we are being told the stories of Peter and Stephen, and that of the second part which narrates St Paul’s missionary journeys.

According to tradition the author of Acts was St Luke, the evangelist who wrote the third gospel – the “earlier work” mentioned in the introductory sentence of Acts. This tradition has been amply confirmed by recent stylometric studies. Luke now emerges as an even more versatile author. It is remarkable that the same man should be responsible both for first-person historical memories in Acts and also for the most memorable of the narratives of Jesus’s infancy – passages which are regarded even by some conservative scholars as symbolic or mythical. The human race is in Luke’s debt for some of the most universally beloved stories in religious literature.

The book of Acts is not at all as well known or loved as the infancy narratives. But it is a remarkable work in its own right. The leading characters, Peter and Paul, are sharply differentiated from each other. Neither is put on a pedestal in the same way as Jesus is in the gospels. We are left wondering what has happened, or is going to happen, to each of the pair. It is instructive to place side by side the narrative of Acts with the epistles that Paul wrote to the different Christian churches. Paul and Luke turn out to be very different people.

The most fascinating part of the Acts is contained in the later chapters where they narrate in the first person the shipwreck of Paul and his recovery on Malta. The story includes details that serve no missionary purpose but were clearly imprinted on the memory of the writer. “As we were making very heavy weather of it, the next day they began to jettison the cargo, and the third day they threw the ship’s gear overboard with their own hands. For a number of days both the sun and the stars were invisible and the storm raged unabated until at last we gave up all hope of surviving.”

Writing the history of Paul’s journeys set a challenge to the narrator. Paul moved from province to province, each with its own governor or proconsul. If the story of his journeys is to maintain historical credibility, the identification of these personages must be reliable. Luke rises to this challenge remarkably effectively. Modern scholars confirm that he has identified correctly all the relevant officials.

Above all, the Acts is a book of reconciliation, bringing together the conflicting groups of Peter’s and Paul’s disciples. At its heart is the council of Jerusalem and the apostolic letter that Paul, Barnabas, Judas and Silas are to take to Antioch and elsewhere releasing Christians from the full obligations of Jewish law. Without the events narrated in Acts Christianity would never have flourished independently but would have remained a minor Jewish sect.

.jpg)