Thanksgiving, like other parts of mainstream American identity, can feel a little Protestant. The Pilgrims, Englishmen who felt that the Church of England had become too popish, were certainly in protest, so much so that they had to leave their native lands to find somewhere even further from the Roman Catholic faith.

Anchoring in Cape Cod, they descended the Mayflower in what is now the state of Massachusetts. The romanticised notion that these brave people initiated a thanksgiving service within moments of landing is generally considered to be apocryphal. What is highly likely, however, is that these deeply religious men and women would have been near continuously praying as they went about their lives. Their prayers would have been more spontaneous than those of the established Church they left behind. Whilst modern scholarship generally considers the first event that laid the foundation for Thanksgiving as a three-day period somewhere between September and early November 1621, these were not their first prayers of thanks for their newfound land.

These early settlers in 1621 were giving thanks for their first successful harvest. Edward Winslow’s Mourt’s relation describes “many of the Indians coming amongst us”, and it appears that the event was celebrated in the presence of around 90 members of the Indigenous Wampanoag people. The setting was far more cordial than the later violence of the Pequot War, which would happen two decades later and claim almost a thousand lives.

Two years later, in 1623, an explicit and religious day of thanksgiving was declared by William Bradford, the second governor of Plymouth Colony. The event was a considerable testament to the enduring faith of those early settlers, who had lost more than half of their original expedition and taken to burying their dead in secret, unmarked graves to avoid showing weakness. The service would have been deeply Puritan, consisting of extempore prayer, Bible readings, and nothing representing liturgical formality. William Brewster, who had secretly operated a printing press in Europe to criticise the Church of England, would likely have presided over the simple affair. In particular, they were giving thanks for the end of a drought and the coming of rains.

However, if their prayers were meant to exude Christian thanksgiving, they omitted one particularly poignant form of thanksgiving: the rite Christ Himself inaugurated. The Holy Mass is the term with which we have become familiar for the liturgy instituted by Christ before His crucifixion. Yet its etymological precision is perhaps lacking. The term derives from the closing words of the Tridentine liturgy, Ite, missa est, meaning “Go, it is the dismissal”.

It might more reasonably be said that a better word for the Mass is the Eucharist. Coming from the Greek word εὐχαριστία, it quite literally means thanksgiving, or thankfulness. Its origins are rooted in gratitude for deliverance from bondage, and it was given by Our Lord as a means to ensure His abiding presence amongst us. The Eucharist is the prayer in which Catholics give thanks for God’s goodness throughout the ages.

The Eucharist thanks God for creation, salvation, the remission of sins, the covenant restored and renewed between God and humanity, for Christ’s presence in the world, for His sacramental presence, and for all good things given to us in daily life. Even though it was absent from the theology of the Puritans at Plymouth, a celebration of the Eucharist would have been the most appropriate thanksgiving, even if their doctrine could not permit it.

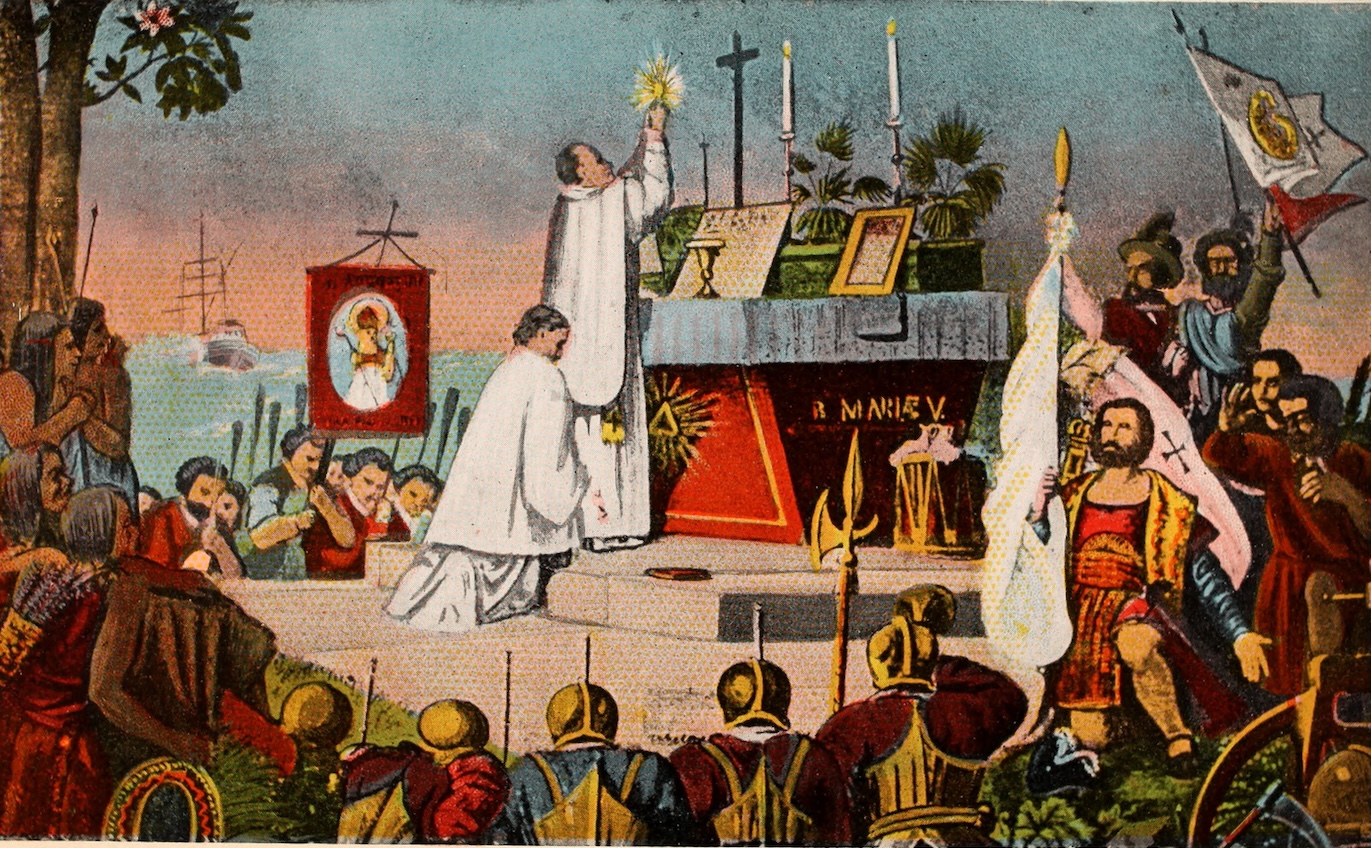

Yet there were settlers whose theology did make allowance for Christ’s instructions at the Last Supper. A group from Cádiz, Spain, sailing under the command of Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, set off on 29 June 1565 with priests included to ensure sacramental ministry. When they landed on 8 September 1565 near present-day St Augustine, Florida, a cross was planted to mark the territory, Mass was celebrated, and the Te Deum was sung in thanksgiving for the newly found land. The date coincided with the feast of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, imbuing the liturgy with Marian solemnity.

For many Catholic Americans, recalling the Puritan events at Plymouth may feel ideologically inconsistent with their faith. But other examples of early settlers provide different foundations for gratitude. Every American, Catholic or otherwise, will have distinct circumstances and graces for which to be thankful. These diverse threads shape the cultural fabric of the United States. What Catholics can share with certainty is that, in Christian worship, the supreme act of thanks giving to God is the sacrifice of the Mass.