Alasdair MacIntyre, a towering figure in moral philosophy and a Catholic convert, has died at the age of 96 years old.

Credited with reviving the discipline of virtue ethics and warning the world about the great moral dangers of modern liberalism, his death on 21 May marks the end of an extraordinary philosophical and spiritual journey and life's work.

This included his seminal 1981 work After Virtue that reshaped contemporary moral and political philosophy, emphasising virtue over utilitarian or deontological frameworks, reportsthe Catholic News Agency (CNA).

It notes that he was known by many as "the most important" modern Catholic philosopher, with MacIntyre’s intellectual and spiritual journey spanning atheism, Marxism, Anglicanism and ultimately Roman Catholicism.

MacIntyre’s striking intellect, razor-sharp wit, and exacting teaching profoundly influenced generations of students and academics, CNA says.

Born in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1929 to Eneas and Greta (Chalmers) MacIntyre, he earned master of arts degrees from the University of Manchester and Oxford. His academic career began in 1951 at Manchester, followed by posts at Leeds, Essex, and Oxford.

In 1969, he moved to the United States, becoming an “intellectual nomad” with appointments as professor of history of ideas at Brandeis University, dean at Boston University, Henry Luce professor at Wellesley, W. Alton Jones professor at Vanderbilt, and McMahon-Hank professor at Notre Dame.

Though he never earned a doctorate, he received 10 honorary doctorates and appointments during his life, quipping at one point: “I won’t go so far as to say that you have a deformed mind if you have a Ph.D., but you will have to work extra hard to remain educated.”

MacIntyre’s After Virtue, deemed a 20th-century philosophical classic, critiqued modern moral fragmentation, advocating a return to Aristotelian ethics. His other works, including Marxism and Christianity, Whose Justice? Which Rationality? and Three Rival Versions of Moral Enquiry, explored moral traditions and rationality.

His spiritual journey was as dynamic as his intellectual one, CNA notes. Initially considering becoming a Presbyterian minister in the 1940s, he became Anglican in the 1950s, then an atheist in the 1960s, famously calling himself a “Roman Catholic atheist” because the Catholic God was “worth denying".

In 1983, at age 55, he embraced Roman Catholicism and Thomism, inspired by his favorite 20th-century theologian, Joseph Ratzinger (the late Pope Benedict XVI), and finally convinced by the Thomist arguments he first encountered as an undergraduate, “not in the form of moral philosophy, but in that of a critique of English culture developed by members of the Dominican order".

"There will be many deserved and heartfelt tributes to his extraordinary career over the coming days, laying out his transformative contributions to moral and political philosophy," Sebastian Milbank writes for the Critic. "But what strikes me, as I reflect upon his work, is just how much we are still living in the world he described, and in no small degree, predicted."

Milbank notes that MacIntyre was a "towering figure, especially for those of who shared his bone deep, intuitive revulsion of modern liberalism", before quoting the great philosopher himself on the topic of liberalism:

“Ever since I understood liberalism, I have wanted nothing to do with it – and that was when I was seventeen years old," MacIntyre said.

His subsequent works, Milbank highlights, still read decades on like the sharpest of contemporary political analysis.

"MacIntyre grasped, perhaps better than any other thinker of his generation, the tragedy inherent in industrialised modernity," Milbank says. "Vast material improvements have come at the apparently inescapable cost of degrading the moral fabric of our common life, alienating and displacing the individual citizen.

"A critic of both capitalism and communism, MacIntyre identified at once how the revolutionary zeal of socialist societies was in practice subordinated to a brutal model of industrial development and exploitation, whilst the social democratic project, though more apparently benign, ultimately did nothing to counter the spiritual degradation of capitalist modernity.

"At a time when the West still seemed a vital and dynamic society, MacIntyre diagnosed the deep-rooted contradictions of an American project in which the 'morality of particularist ties and solidarities has been conflated with a morality of universal, impersonal and impartial principles'."

This "latent tension that MacIntyre identified back in 1984 has since exploded into a divided America," Milbank says, "with wild swings from the messianic liberal universalism of the neoliberal and progressive projects, to the America First politics of Trump and Vance."

Milbank describes how MacIntyre "looked to the development of 'a new set of social forms' on the scale of those wrought by St Benedict. These are to be understood not as a shelter from progressivism, but as a coherent economic, political and ethical model, with its own unique institutional architecture, with its aim to entirely oppose the logic that we all live by."

It all leaves Milbank considering that "there is a sombre providential symmetry in Alisdair MacIntyre dying as a new Pope takes on the name of Leo XIV, treading in the footsteps of the author of Rerum Novarum".

Through all his conversions, MacIntyre emphasised that the study of ethics cannot be separated from history, for it is an understanding of historically situated practices within communities that is needed to make sense of moral judgments, writesDr. Christopher Kaczor, Honorary Professor for the Renewal of Catholic Intellectual Life at the Word on Fire Institute.

"MacIntyre saw no contradiction between his faith and his philosophy," Kaczor says. "He viewed them as mutually enriching."

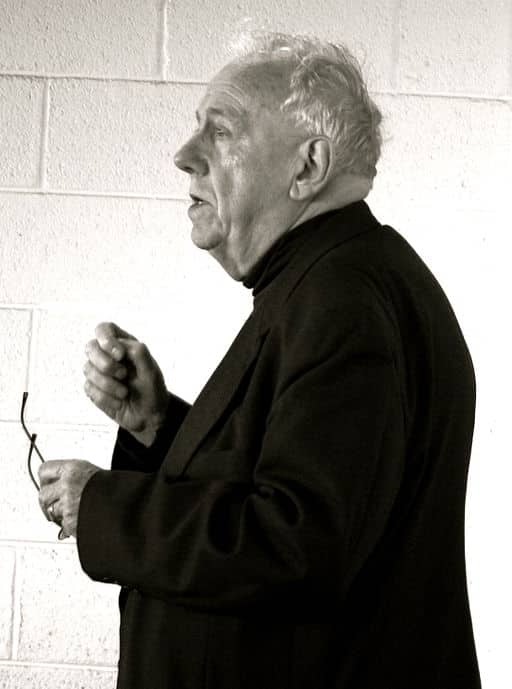

Photo: Alasdair MacIntyre at The International Society for MacIntyrean Enquiry conference held at the University College Dublin, Ireland, 9 March 2009. (Credit: Wikimedia Creative Commons.)

Alasdair MacIntyre, a towering figure in moral philosophy and a Catholic convert, has died at the age of 96 years old.

Credited with reviving the discipline of virtue ethics and warning the world about the great moral dangers of modern liberalism, his death on 21 May marks the end of an extraordinary philosophical and spiritual journey and life's work.

This included his seminal 1981 work <a href="https://undpress.nd.edu/9780268035044/after-virtue/" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener"><mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color"><em>After Virtue</em></mark></a> that reshaped contemporary moral and political philosophy, emphasising virtue over utilitarian or deontological frameworks, <mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color"><a href="https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/news/264325/renowned-philosopher-and-catholic-convert-alasdair-macintyre-dies-at-96">reports</a> </mark>the <em>Catholic News Agency (CNA)</em>.

It notes that he was known by many as "the most important" modern Catholic philosopher, with MacIntyre’s intellectual and spiritual journey spanning atheism, Marxism, Anglicanism and ultimately Roman Catholicism.

MacIntyre’s striking intellect, razor-sharp wit, and exacting teaching profoundly influenced generations of students and academics, <em>CNA</em> says.

Born in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1929 to Eneas and Greta (Chalmers) MacIntyre, he earned master of arts degrees from the University of Manchester and Oxford. His academic career began in 1951 at Manchester, followed by posts at Leeds, Essex, and Oxford.

In 1969, he moved to the United States, becoming an “intellectual nomad” with appointments as professor of history of ideas at Brandeis University, dean at Boston University, Henry Luce professor at Wellesley, W. Alton Jones professor at Vanderbilt, and McMahon-Hank professor at Notre Dame.

Though he never earned a doctorate, he received 10 honorary doctorates and appointments during his life, quipping at one point: “I won’t go so far as to say that you have a deformed mind if you have a Ph.D., but you will have to work extra hard to remain educated.”

MacIntyre’s <em>After Virtue</em>, deemed a 20th-century philosophical classic, critiqued modern moral fragmentation, advocating a return to Aristotelian ethics. His other works, including <em>Marxism and Christianity</em>, <em>Whose Justice? Which Rationality?</em> and<em> Three Rival Versions of Moral Enquiry</em>, explored moral traditions and rationality.

His spiritual journey was as dynamic as his intellectual one, <em>CNA </em>notes. Initially considering becoming a Presbyterian minister in the 1940s, he became Anglican in the 1950s, then an atheist in the 1960s, famously calling himself a “Roman Catholic atheist” because the Catholic God was “worth denying".

In 1983, at age 55, he embraced Roman Catholicism and Thomism, inspired by his favorite 20th-century theologian, Joseph Ratzinger (the late Pope Benedict XVI), and finally convinced by the Thomist arguments he first encountered as an undergraduate, “not in the form of moral philosophy, but in that of a critique of English culture developed by members of the Dominican order".

"There will be many deserved and heartfelt tributes to his extraordinary career over the coming days, laying out his transformative contributions to moral and political philosophy," Sebastian Milbank <a href="https://thecritic.co.uk/still-living-in-macintyres-world/"><mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color">writes</mark></a> for the <em>Critic</em>. "But what strikes me, as I reflect upon his work, is just how much we are still living in the world he described, and in no small degree, predicted."

Milbank notes that MacIntyre was a "towering figure, especially for those of who shared his bone deep, intuitive revulsion of modern liberalism", before quoting the great philosopher himself on the topic of liberalism:

“Ever since I understood liberalism, I have wanted nothing to do with it – and that was when I was seventeen years old," MacIntyre said.

His subsequent works, Milbank highlights, still read decades on like the sharpest of contemporary political analysis.

"MacIntyre grasped, perhaps better than any other thinker of his generation, the tragedy inherent in industrialised modernity," Milbank says. "Vast material improvements have come at the apparently inescapable cost of degrading the moral fabric of our common life, alienating and displacing the individual citizen.

"A critic of both capitalism and communism, MacIntyre identified at once how the revolutionary zeal of socialist societies was in practice subordinated to a brutal model of industrial development and exploitation, whilst the social democratic project, though more apparently benign, ultimately did nothing to counter the spiritual degradation of capitalist modernity.

"At a time when the West still seemed a vital and dynamic society, MacIntyre diagnosed the deep-rooted contradictions of an American project in which the 'morality of particularist ties and solidarities has been conflated with a morality of universal, impersonal and impartial principles'."

This "latent tension that MacIntyre identified back in 1984 has since exploded into a divided America," Milbank says, "with wild swings from the messianic liberal universalism of the neoliberal and progressive projects, to the America First politics of Trump and Vance."

Milbank describes how MacIntyre "looked to the development of 'a new set of social forms' on the scale of those wrought by St Benedict. These are to be understood not as a shelter from progressivism, but as a coherent economic, political and ethical model, with its own unique institutional architecture, with its aim to entirely oppose the logic that we all live by."

It all leaves Milbank considering that "there is a sombre providential symmetry in Alisdair MacIntyre dying as a new Pope takes on the name of Leo XIV, treading in the footsteps of the author of Rerum Novarum".

Through all his conversions, MacIntyre emphasised that the study of ethics cannot be separated from history, for it is an understanding of historically situated practices within communities that is needed to make sense of moral judgments, <mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color"><a href="https://www.wordonfire.org/articles/remembering-alasdair-macintyre-1929-2025/">writes</a> </mark>Dr. Christopher Kaczor, Honorary Professor for the Renewal of Catholic Intellectual Life at the Word on Fire Institute.

"MacIntyre saw no contradiction between his faith and his philosophy," Kaczor says. "He viewed them as mutually enriching."

<em>Photo: Alasdair MacIntyre at The International Society for MacIntyrean Enquiry conference held at the University College Dublin, Ireland, 9 March 2009. (Credit: Wikimedia Creative Commons.)</em>