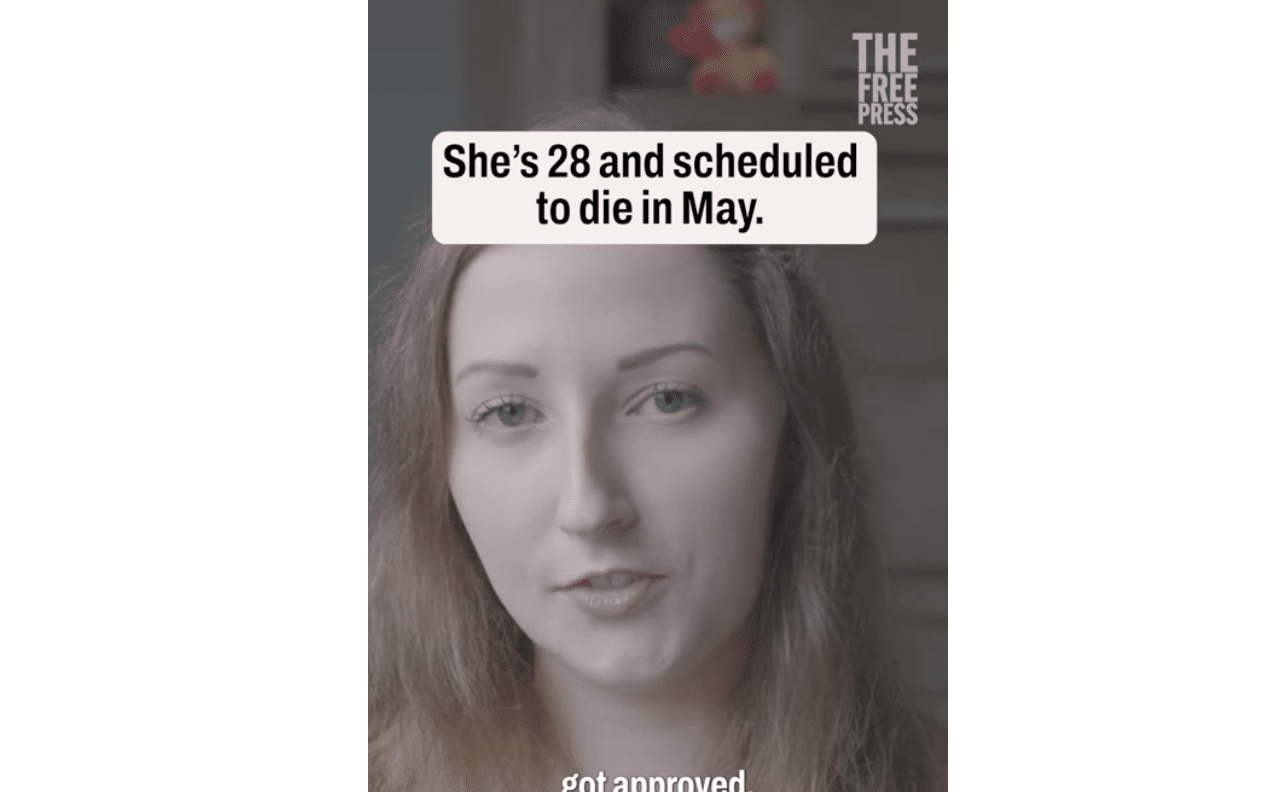

<a href="https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-13458499/Zoraya-ter-Beek-healthy-Dutch-woman-dies-euthanasia.html"><strong>Reports</strong></a> have emerged that Zoraya ter Beek, a young woman from the Netherlands, died on 22 May by euthanasia. She was 29 years old.

In the weeks leading up to her death, Zoraya found herself in a media storm. She became at once an object of pity and of judgement. Some called her brave, many called her selfish. Most of us simply couldn’t understand; she was physically healthy and seemingly had a support network. How could someone so young want life to end so desperately?

As <a href="https://www.thefp.com/p/im-28-and-im-scheduled-to-die"><strong>reported</strong></a> by <em>The Free Press</em>, she dealt with depression, autism and borderline personality disorder. And according to a <em>Guardian </em><a href="https://www.theguardian.com/society/article/2024/may/16/dutch-woman-euthanasia-approval-grounds-of-mental-suffering"><strong>article</strong></a> from just days before her death, "she embarked on intensive treatments, including talking therapies, medication and more than 30 sessions of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)".

While initially she was hopeful, Zoraya explained that "the longer the treatment goes on, you start losing hope". After spending over three years on a waiting list, an appointment was booked, and doctors administered fatal drugs to her. Zoraya had considered committing suicide before, but said that "the violent death by suicide of a schoolfriend and its impact on the girl’s family deterred her". And although she claimed never to have felt hesitation once the decision was made, she did admit to feeling "guilt" over the devastating effect that her death would inevitably have on her partner, family and friends.

As Christians, we should of course denounce Zoraya’s decision, and yet the blame does not lie with her alone. We must avoid the temptation to dismiss the severity of mental suffering, simply putting her behaviour down as "selfishness". We can’t condemn Zoraya, as God, who alone knows the fate of her immortal soul, can truly do that. What we must do instead is condemn the policies that have made deaths like hers not only possible, but also more likely.

Firstly, we need to dispel the myth that assisted dying is more humane, and that legalising it will reduce the number of suicides. Let’s look at what happens when both assisted suicide (meaning the patient self-administers life-ending drugs, provided by medical professionals) and euthanasia (when the life-ending drugs are given to the patient <em>by</em> medical professionals) are <em>both </em>legalised. Since MAID was introduced in 2016, Canada’s suicide rate has not significantly changed, but cases of assisted dying have steadily increased year by year. Assisted dying, we are often told, gives people in distress a chance to exert autonomy over their bodies. And yet, as professor David Albert Jones has <a href="https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/20502877.2024.2307698?scroll=top&needAccess=true"><strong>shown</strong></a>, 99 per cent of patients are reluctant to self-administer, choosing euthanasia over assisted suicide; of the ones choosing to self-administer, a sizeable proportion do not go through with it in the end.

What does this tell us? It reveals that assisted dying is not really about autonomy, but rather about surrendering control to doctors. Something that struck me about Zoraya’s story is, ironically, her stubborn desire to live. According to the <em>Free Press </em>article mentioned above, she remembered her psychiatrist "telling her that they had tried everything", that "there’s nothing more we can do for you. It’s never gonna get any better". Her death may have been a choice, but it was influenced by a trusted medical professional. In this way, the doctor’s expertise becomes a tragic replacement of God’s love. Zoraya deserved doctors who cherished her life as precious, just as God sees each of our lives as infinitely precious. That is not what she got.

People contemplating assisted dying, especially for mental health reasons, are often the members of a society who feel the most neglected, lonely and unwanted. Being granted access to euthanasia may well be, paradoxically, the only time that the enormity of their pain is acknowledged. But instead of receiving care, the laws of countries such as the Netherlands and Canada communicate to their citizens that their pain is inconvenient. It may not be spelled out, but the implication is there. "I did not want to burden my partner with having to keep the grave tidy," Zoraya said when explaining her choice to be cremated. I wonder in how many other ways she felt a burden to her boyfriend, her friends and her doctors. I wonder, as year after year the medical treatment she received failed to ease her suffering, if she was ever told that she was loved regardless of her mental health struggles. I wonder if, as those very people who should have kept Zoraya safe stopped fighting for her life, they told themselves the lie that her death was somehow compassionate.

Zoraya’s story reminds me terribly of the fate of the fictional character of Mabel in Robert Hugh Benson’s 1907 dystopian novel <em>The Lord of the World</em>. In the future England described by Benson, a new world "religion" – an atheistic kind of humanism – has been enforced. Mabel is a young woman who, despite not being a Christian herself, has become horrified by the vicious persecutions of the few remaining Catholics. Witnessing the brutal murdering of priests and even children causes her to sink further and further into despair, and she eventually seeks access to assisted suicide, which, Benson presciently imagines, has become legal and available in most countries.

Mabel retains on some level a strong desire to live. In the days leading up to her death, we are told, her "agony" can only be pacified by "the half-hinted promise of some deeper voice suggesting that death was not the end". But, like Zoraya, Mabel believes, in Benson’s words, that her death is an act of charity: "There was a certain pitch of distress at which the individual was no longer necessary to himself or the world; it was the most charitable act that could be performed." Of course, both Mabel and her real-life counterparts must be held accountable for giving into despair. But they cannot bear the blame exclusively. Laws teach. If suicide is legalised, it’s only a matter of time before women and men like Zoraya imbibe the message that a life of acute mental or physical distress is just too burdensome for society to bear.

With news stories similar to Zoraya’s being increasingly common, it’s easy to become habituated to their tragedy, or even to absorb the opposing side’s rhetoric of "compassionate death" or "dignity in dying". We must resist this. We must remind ourselves that eradicating pain is not charity or compassion. On the other hand, to be compassionate is to continue to love those in distress <em>through </em>their pain.

As Catholics, we have a powerful message to tell that there is value to be found in suffering: when we step into church, we are met with the sight of Christ crucified, and are reminded of the agony he bore because he loved us. In fact, it’s because Christ experienced being human that we can be sure that he understands and cares for us in <em>our </em>suffering. Still, most of us are not lawmakers. We’re not campaigners or politicians. Trying to justify our Catholic beliefs to the world can seem overwhelming – almost pointless, when our faith is so often denigrated.

As Catholics, we must continue to remind ourselves of the power of prayer; not exclusively praying for a change of heart of those in positions of power who may choose to legalise assisted dying, though that is of course important, but rather praying in order to cultivate closeness to God in our own lives. We must rely on God first, and only then can we show others that we can help them bear their pain. We must confide in the one who bore the greatest pain for us, and petition, in prayer, to be given the strength to imitate his goodness and his compassion in our own lives. Finally, we must never lose hope, even in cases where a person appears determined to die. We must pray for them to the very end, for by God’s grace, no soul is ever truly beyond saving.

<em>(Screenshot from YouTube) </em>