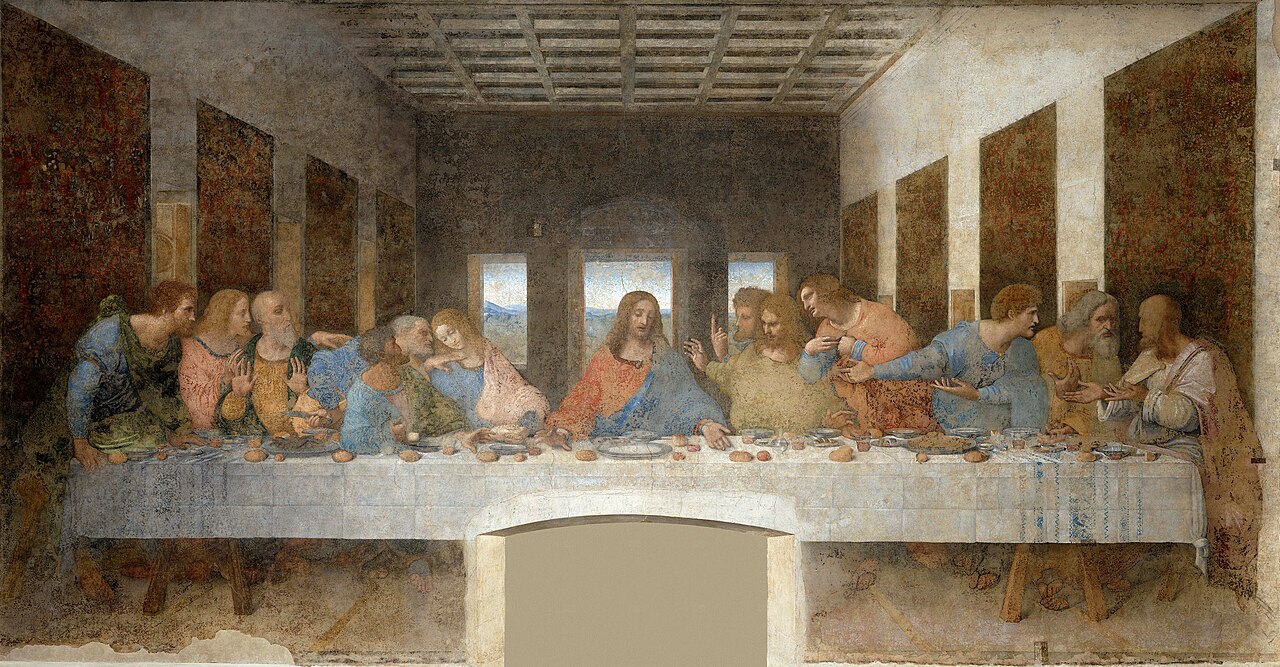

Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper sprang to prominence in the public mind during the summer, when a pastiche of the work was presented by a group of assorted drag queens and lesbians offering a distorted pantomime as an act of contemptuous transgression. It was almost certainly intended to be a poke in the eye for the Catholic Church, whose moral teachings form a rebuke to a quest for an unrestrained hedonism.

The organisers set out to reproduce the classic moment of intimacy between Jesus and His apostles, replacing the night before Christ’s crucifixion with a panoply of alternative, sexualised characters. In choosing one of the most profoundly beautiful objects of art as a launching pad for mockery and denigration, it was as if they invited viewers to engage in a comparison between two worldviews, two cultures and two civilisations.

As it happens, Leonardo’s painting embodies two of the themes the drag artists presented us with: change, in the form of trans-sexuality, and also betrayal. It might be said that the hedonistic artists themselves are engaged in a deliberate anarchic act of betrayal of their own foundational culture, promoting the trans element of sexual cultural experimentation.

But the Last Supper has its own “trans” dimension, because the miracle of the Mass is also about change. Through transubstantiation bread and wine become the Body and Blood of Jesus, and then effect a slow but intense further transformation of the believer’s heart and soul. “Trans” is all about change. Both the Church and the trans community are about change, but from wholly opposite directions.

Trans change attempts to solve the problem of a mind that has convinced itself that it is in the wrong body; whereas transformation in the Holy Spirit seeks the liberation of a soul trapped by self-will and an intrinsic attraction to rebellion – in other words, original sin.

Conceptually, change and the direction of change lie at the heart of the “Last Supper”, which Leonardo da Vinci created with such exquisite insight. But another element of the tableau is the capturing of the moment of betrayal that Jesus announces. Love always risks betrayal. The Incarnation confronted the capacity for betrayal that lurks in the human heart, in order to heal it with forgiveness and restitution. The mockery of Christian culture and all the freedoms that it has accumulated is just one more extension of the initial betrayal that the scene of the Last Supper captures.

It is not only the elements of bread and wine that are going to undergo a miraculous transformation, but also any human heart that finds itself weighted down with the need for forgiveness. At the Last Supper the frailty of the human heart is exposed as Jesus warns His apostles, in this intense moment of change, that one of them will betray Him and instigate His death and sacrifice.

“Lord, is it I?” It is, of course, Judas. He too is an apostle of change; he has decided that a change of messianic direction is needed, and he is going to provide it by placing Jesus in a trap that will put Him in the hands of the Romans.

The route Judas has taken is one variation of a theme that most of us are familiar with. It is one that colours all revolutionary movements: that things can be changed for the better by choosing this or that course of action. It is symptomatic of our capacity for trans-illusion that we ourselves can mend the deficiencies of human nature by one project or another.

The betrayal, however, is not limited to Judas. The pressure of the events he unleashes will expose the fragility and vulnerability of each apostle. Most will run away. Peter will deliberately deny knowing Jesus. Thomas will go AWOL. He is identified in the painting by his raised finger in protest; the same finger with which Jesus will invite him to probe His post-Resurrection wounds. After the arrest of Jesus, the apostles will melt away into the night and (apart from John, standing with Our Lady at the foot of the Cross) will disappear until the early-morning news of the Resurrection draws them out of their hiding places.

Perhaps the most immediate transition is that marking the move from unbelief to faith in the Resurrection. The Last Supper marks the start of the process of the collapse into fear becoming the confidence and joy of the apostolic Church, once the disciples have personally encountered the risen Christ.

The apostles would make a terrifying journey into the oncoming dark hounded by fear, unbelief, tragedy, uncertainty and suffering. They too would experience change, a transition from despair to hope, from unbelief to faith, from darkness to light, from despair to joy.

The quest for change and the risk of betrayal is hard-wired into the human condition. The opening ceremony of the Paris Olympics presented all those who watched with two different and opposing patterns and quests for change. One was directed to the body, sensual and secular; the other to the soul, promising a renewal of mind and heart that defies the limitations of time and space.

<strong><strong>This article appears in the September 2024 edition of the <em>Catholic Herald</em>. To subscribe to our award-winning, thought-provoking magazine and have independent and high-calibre counter-cultural and orthodox Catholic journalism delivered to your door anywhere in the world click <a href="https://catholicherald.co.uk/subscribe/?swcfpc=1"><mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color">HERE</mark></a></strong></strong>.