If you’ve been to any previous exhibitions at the former Queen’s Gallery, now the King’s Gallery, at Buckingham Palace (I’ve covered several for the <em>Herald</em>, including Charles II, Canaletto, and Russia, Royalty & the Romanovs), you’d expect big colourful paintings. <em>Drawing the Italian Renaissance</em> is very different. Grandeur is replaced with subtlety. But it’s a paradox: it’s quiet, subdued, largely monochrome; on the other hand, it comes over as busy and almost cluttered, with some walls holding a dozen works – around 160 in all, from over 80 artists.

The Royal Collection is one of the largest and most prestigious art collections in the world – and one of the oldest. Dispersed after the execution of Charles I in 1649, it was refounded by Charles II following the Restoration in 1660. Over the centuries monarchs have added to it, largely following their personal taste. Many of the works in this exhibition, including a small selection from a priceless album of 600 drawings by Leonardo da Vinci, were acquired by Charles II himself.

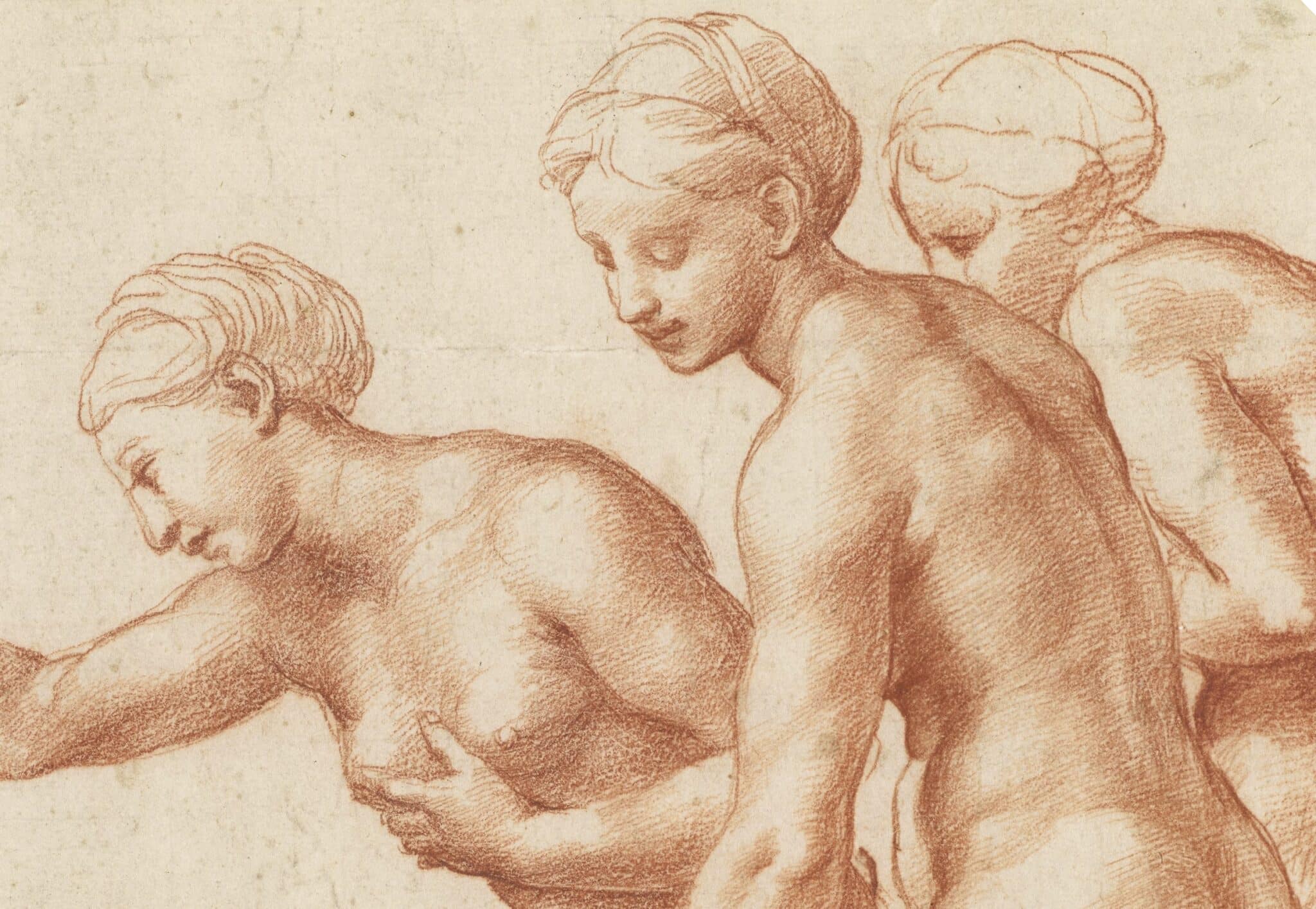

Leonardos nestle up with Michelangelos and Raphaels. Nearly all artists, and most models, were male – but Raphael’s sketch in red chalk of the <em>Three Graces</em> is three poses of the same nude woman, a study for the group in his fresco <em>The Wedding Feast of Cupid and Psyche</em>. Another red-chalk sketch by Raphael is of a group of men in everyday clothes, to establish the poses of figures in his design for a tapestry of <em>Christ’s Charge to Peter</em>, commissioned by Pope Leo X. Another drawing is of St Paul striking the sorcerer Elymas blind, leading to the conversion of the Roman proconsul Sergius Paulus (Acts 13). Raphael’s drawing is a final study for his full-size cartoon, which would then have been woven as a tapestry for the Sistine Chapel. Seven of his series of cartoons are in the Royal Collection.

Leonardo is well represented in the exhibition, displaying the range of his interests. Learning how to show realistically the way that drapery folds and falls was one of the skills of Renaissance artists. A brush-and-ink drawing of the drapery of a kneeling figure is a study for the angel in his altarpiece of the <em>Virgin of the Rocks</em> in the National Gallery. But it’s the room on Observing Nature that really displays Leonardo’s devotion to detail: a study of storm clouds; a beautifully detailed relief map of southern Tuscany; a botanical study, studies of a horse for a statue (he made a full-scale model and mould, but it was never cast); a delightful sheet of around 20 drawings of domestic cats, lions and a dragon; an anatomical drawing of the muscles, tendons and ligament of a bear’s foot; the uterus of a pregnant cow; the anatomy of a bird’s wing.

In other rooms there’s yet more Leonardo: a costume study for a masque at the court of King Francis I of France; a detailed study of the muscles of the human trunk and the leg. Leonardo, like his contemporary Michelangelo, whose anatomical studies are also here, dissected corpses to find how the human body worked.

It’s not always clear what the original purpose of a drawing might have been. Was Michelangelo’s <em>Virgin and Child</em> with the Young Baptist a design for a sculpture, or a personal devotional work? And whether a study or a finished work, Michelangelo’s <em>The Risen Christ</em> (c.1532) is astonishing, a male nude leaping joyfully from the grave – surely an inspiration for William Blake’s <em>Albion Rose</em> over 250 years later.

But most of the drawings in this exhibition were intended as working studies, for either the artist or someone else to develop into a painting or the applied arts – tapestries, statues, architecture, metalwork and more. There are drawings that would become etchings for reproduction; there’s a design for a tomb; another for a lavish marble altar; one for a painted wooden ceiling. There’s a design for a candelabrum and another for a ceremonial mace; an illustration of a scene from Virgil’s <em>Aeneid</em> that will become a bronze medal; designs for stucco work for Pope Julius III’s private residence, and for the Sala Regia in the Vatican; there’s even an architectural plan for the rebuilding of St Peter’s in Rome. Many of these are by artists most of us will not have heard of.

Artists didn’t just draw finished pictures – they were part of a creative industry, working together with others who would turn their vision into something else. As curator Martin Clayton points out, these artists would be astonished to know that centuries later their working sketches for another craftsman would be framed and displayed in a gallery. A few, displayed in the final room, were intended as finished works of art in themselves, perhaps as gifts for a patron.

Why was there an upsurge in drawing in the Renaissance? Largely, says Clayton, because paper became widely available and cheap once printing began in the 1450s. Drawing was how all young apprentice-artists began a career, honing their skills by copying their masters’ work before developing their own style. The earliest work in the exhibition, from 1460-80, shows a young man hunched over a sheet of paper while a dog sleeps nearby.

The exhibition might have done better to have had fewer works, displayed more sparingly, and with more explanation and background. Apart from the short introductory paragraph in each room, there is only a brief label with each drawing. As a whole, the exhibition needs more narrative, more context; without it, for the casual browser, it’s just a collection of 160 drawings – albeit some amazing ones by some of the most famous artists who ever lived. But this is very much an exhibition aimed at artists. Many of the labels mention techniques that were used to develop a drawing into the final work, such as pricking through the design, or squaring the picture so that it could be copied accurately a little at a time.

This exhibition links Charles II, who probably acquired most of the nearly 2,000 Renaissance drawings in the Royal Collection, with his present successor, Charles III, who has also for decades been a patron of the arts. Three artists-in-residence will be present throughout the four months that the drawings are on display; all have done postgraduate studies at the Royal Drawing School, established by the King in 2000, when he was Prince of Wales. Visitors to the exhibition are encouraged to pick up a sheet of paper and a pencil, and sit in front of the exhibits and draw.

Unusually, instead of a catalogue, this exhibition has an artist’s workbook, <em>Be Inspired: To Draw Like a Renaissance Master</em>, containing half-a-dozen reproductions of Renaissance works to be copied and to provide inspiration. As one of the artists-in-residence, Sara Lee Roberts, says: “A wonderful time-travelling can occur while drawing – my hand, eyes and brain are put in touch with those of the long-dead artist. I feel a companionship, a common humanity.”

Drawing the Italian Renaissance<em> is at the King’s Gallery at Buckingham Palace until 9 March 2025</em>