The Archbishop of Canterbury, the Most Revd Justin Welby, has resigned in the wake of increasing public anger about the way in which the leader of the Anglican Communion failed to handle a safeguarding crisis produced by an evangelical layman, John Smyth, who beat young boys (in the purported context of giving them spiritual direction) until they bled.

About 130 boys and adolescents were thrashed, in Smyth's soundproof shed, in the context of an Evangelical summer camp that drew boys from the UK's leading public school. Archbishop Welby's office, it emerged in the course of an investigation carried out by Keith Makin, was directly responsible for a lack of interest. Delayed again and again, it therefore took 10 years for the truth to come into the light, during which time Smyth, the perpetrator of the abuse, died.

The Makin Review finally appeared last week. Smyth's victims responded: “We note that publication of the Makin Review is more than 1630 days late. Justice delayed is justice denied, particularly to all those John Smyth victims who have now died. We attribute the vast majority of that delay to the deliberate under-resourcing of the project by the Church of England. We have been making this point to the CofE for the last five years."

Archbishop Welby accepted that he was at fault, but even up to last night was steadfastly refusing to resign. Yet there is always a price to be paid for moral failure; that’s the kind of universe we live in. Christians understand it better than most, and one would hope that an Archbishop might understand that better than most Christians. The facts have not been well presented in the media, but they matter.

Smyth was a barrister – a Queen's Counsel, no less – who came to dominate an Evangelical sub-culture within the Church of England and violently molested over one hundred young men, whom he met through the summer camps which he ran for the Iwerne Trust. The poshest boys from the poshest schools were invited to those camps as future Evangelical leaders of Church and State.

In 1984, as murmurs arose about his activities, Smyth slipped over to Zimbabwe to set up camps of his own there. This culminated in his arrest, in 1997, on suspicion of culpable homicide, after the death of 16-year-old Guide Nyachuru, whose unclothed body was found in a school swimming pool in December 1992. Thereafter Smyth fled to South Africa.

Back in England, despite the prolific nature of Smyth's activities, a culture of secrecy continued to prevail. After 1984, it was common knowledge that something corrupt and dreadful had happened, but no one with any responsibility for the Iwerne camps was talking.

In 2013 Archbishop Welby was officially informed of the scale and scope of the problem, and asked to act. But there was a problem. He had himself been one of the senior boys helping run the Iwerne project, and was involved personally. He didn’t act. And so the question "how much did he know?" has become important.

Many of the people involved, when asked, said they knew nothing or had forgotten. That included Lord Carey of Clifton, Archbishop Welby's predecessor-but-one and also an Evangelical, and Archbishop Welby himself. Talking to Nick Ferrari in 2017, Archbishop Welby claimed he went to work in Paris between 1978 and 1983 and had no contact with the people involved at all during that period.

But the records show that in 1979 Archbishop Welby was listed as a speaker at the summer camp, and in 1983 greeted Smyth at the Anglican chaplaincy in Paris one Sunday as Smyth passed through with a cohort of boys. These are unhappy contradictions.

Fast forward to 2013, when the full horror of Smyth's activities was brought to Archbishop Welby's door at Lambeth Palace. It then became his personal and institutional responsibility to establish what happened and why it happened, and to whom – and then institutional failure somehow set in.

The blow-by-blow story of what happened under Archbishop Welby from that point on is astonishing; ten years later, the Makin Review details exactly what happened. The quickest way of grasping the scale of incompetence and the damage done is to ask the victims. They have responded to the latest report with misery and the deepest morally energised frustration.

In a commentary they write that they are “concerned that the Review demonstrates that the entire Church hierarchy still has no understanding of a trauma-informed approach despite this being established many times previously”.

The report, however, demonstrates that perhaps one of the most egregious personal failures by Archbishop Welby emerged when, in what is now a notorious 2017 LBC interview, he made specific assurances that the activities of John Smyth had been reported as a crime to the police.

The Church was not dealing with it, perhaps, but the police were. But this wasn’t true. His office had not reported it to the police and that was one of the reasons why, until Kathy Newman got involved in 2017, nothing happened.

Kathy Newman recently interviewed Archbishop Welby to ask if the failure to bring Smyth's abuse – and the failures to expose and contain – it to light constituted a cover-up. After all, not exposing it allows it to remain covered up, and a refusal to act is in itself an action.

The Archbishop’s reply was devastating.

KN: “Are you ever torn between doing what’s right and protecting the institution?”

JW:“No… I don’t give a hang about the institution, I really, genuinely don’t. If this report was a lethal blow to the institution, so be it. God will raise up another institution.

KN: “So your failing is incompetence rather than cover up – your personal failing?”

JW: “Yes, incompetence; yes, alright. I’ll give you that one.”

If you are a victim the fact that you have had neither proper help, recognition or redress because of uselessness rather than mendacity, makes little difference. Archbishop Welby failed to act to expose the corruption that had polluted the Evangelical enterprise that he represented and was part of, and someone has finally accepted responsibility for the failure to do what needed to be done to bring it to light, acknowledge it and help those wounded by it.

One Anglican clergyman, the Revd Fergus Butler-Gallie, wrote to Archbishop Welby last week, putting the moral case at its most poignant.

“We will continue to pray for you, but I for one will be praying that you will resign. The damage you have done to this church will take a very long time to repair. More importantly, those things you did and failed to do inflicted such damage on people—made in the image of that same God—might never heal. Any healing of individuals or the institution must now be in His hands, not yours. The way you might serve that process best now is to resign. If you will not go for the love of the institution, if you will not go for the love of its people and priests, if you will not go for the victims, if you will not go for reasons of your own embarrassment or shame, then I pray you; for love of God, and Him alone, go.”

Mr Butler-Gallie's prayers have now been answered, and Archbishop Welby has stepped down "having sought the gracious permission of His Majesty The King". Whether his successor will usher in any kind of substantive change of culture in the higher echelons of the Church of England, remains to be seen.

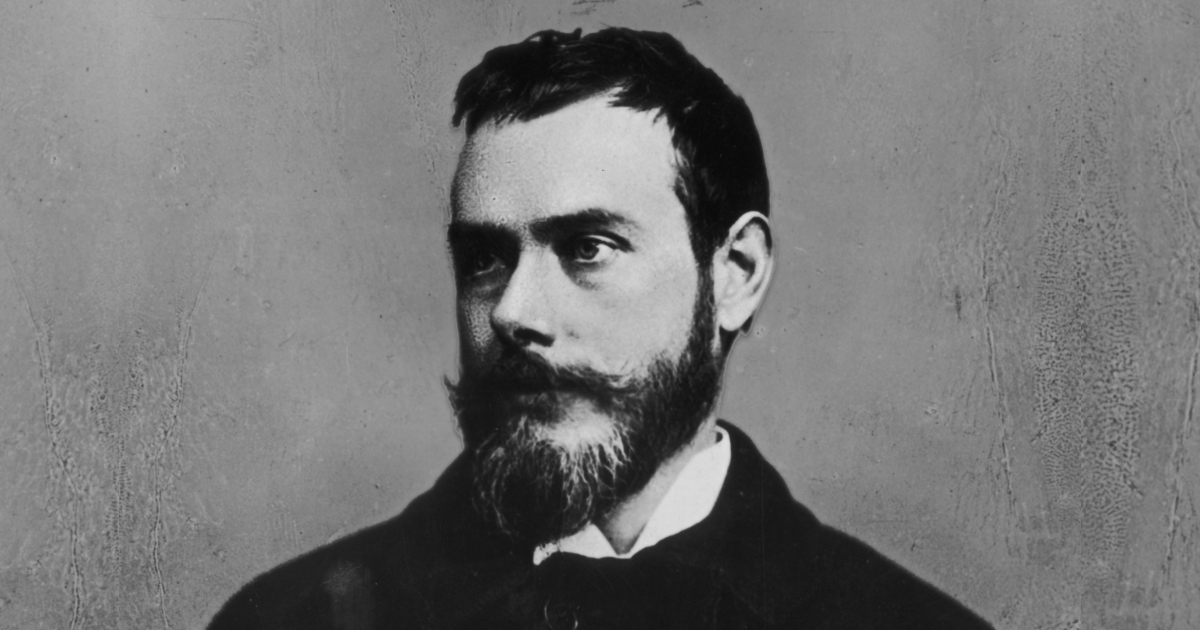

Archbishop Welby with Pope Francis in Rome, earlier this year. Photo by Filippo MONTEFORTE / AFP via Getty Images

The Archbishop of Canterbury, the Most Revd Justin Welby, has resigned in the wake of increasing public anger about the way in which the leader of the Anglican Communion failed to handle a safeguarding crisis produced by an evangelical layman, John Smyth, who beat young boys (in the purported context of giving them spiritual direction) until they bled.

About 130 boys and adolescents were thrashed, in Smyth's soundproof shed, in the context of an Evangelical summer camp that drew boys from the UK's leading public school. Archbishop Welby's office, it emerged in the course of an investigation carried out by Keith Makin, was directly responsible for a lack of interest. Delayed again and again, it therefore took 10 years for the truth to come into the light, during which time Smyth, the perpetrator of the abuse, died.

The Makin Review finally appeared last week. Smyth's victims responded: “We note that publication of the Makin Review is more than 1630 days late. Justice delayed is justice denied, particularly to all those John Smyth victims who have now died. We attribute the vast majority of that delay to the deliberate under-resourcing of the project by the Church of England. We have been making this point to the CofE for the last five years."

Archbishop Welby accepted that he was at fault, but even up to last night was steadfastly refusing to resign. Yet there is always a price to be paid for moral failure; that’s the kind of universe we live in. Christians understand it better than most, and one would hope that an Archbishop might understand that better than most Christians. The facts have not been well presented in the media, but they matter.

Smyth was a barrister – a Queen's Counsel, no less – who came to dominate an Evangelical sub-culture within the Church of England and violently molested over one hundred young men, whom he met through the summer camps which he ran for the Iwerne Trust. The poshest boys from the poshest schools were invited to those camps as future Evangelical leaders of Church and State.

In 1984, as murmurs arose about his activities, Smyth slipped over to Zimbabwe to set up camps of his own there. This culminated in his arrest, in 1997, on suspicion of culpable homicide, after the death of 16-year-old Guide Nyachuru, whose unclothed body was found in a school swimming pool in December 1992. Thereafter Smyth fled to South Africa.

Back in England, despite the prolific nature of Smyth's activities, a culture of secrecy continued to prevail. After 1984, it was common knowledge that something corrupt and dreadful had happened, but no one with any responsibility for the Iwerne camps was talking.

In 2013 Archbishop Welby was officially informed of the scale and scope of the problem, and asked to act. But there was a problem. He had himself been one of the senior boys helping run the Iwerne project, and was involved personally. He didn’t act. And so the question "how much did he know?" has become important.

Many of the people involved, when asked, said they knew nothing or had forgotten. That included Lord Carey of Clifton, Archbishop Welby's predecessor-but-one and also an Evangelical, and Archbishop Welby himself. Talking to Nick Ferrari in 2017, Archbishop Welby claimed he went to work in Paris between 1978 and 1983 and had no contact with the people involved at all during that period.

But the records show that in 1979 Archbishop Welby was listed as a speaker at the summer camp, and in 1983 greeted Smyth at the Anglican chaplaincy in Paris one Sunday as Smyth passed through with a cohort of boys. These are unhappy contradictions.

Fast forward to 2013, when the full horror of Smyth's activities was brought to Archbishop Welby's door at Lambeth Palace. It then became his personal and institutional responsibility to establish what happened and why it happened, and to whom – and then institutional failure somehow set in.

The blow-by-blow story of what happened under Archbishop Welby from that point on is astonishing; ten years later, the Makin Review details exactly what happened. The quickest way of grasping the scale of incompetence and the damage done is to ask the victims. They have responded to the latest report with misery and the deepest morally energised frustration.

In a commentary they write that they are “concerned that the Review demonstrates that the entire Church hierarchy still has no understanding of a trauma-informed approach despite this being established many times previously”.

The report, however, demonstrates that perhaps one of the most egregious personal failures by Archbishop Welby emerged when, in what is now a notorious 2017 LBC interview, he made specific assurances that the activities of John Smyth had been reported as a crime to the police.

The Church was not dealing with it, perhaps, but the police were. But this wasn’t true. His office had not reported it to the police and that was one of the reasons why, until Kathy Newman got involved in 2017, nothing happened.

Kathy Newman recently interviewed Archbishop Welby to ask if the failure to bring Smyth's abuse – and the failures to expose and contain – it to light constituted a cover-up. After all, not exposing it allows it to remain covered up, and a refusal to act is in itself an action.

The Archbishop’s reply was devastating.

<em>KN</em>: “Are you ever torn between doing what’s right and protecting the institution?”

<em>JW</em>:<em> </em>“No… I don’t give a hang about the institution, I really, genuinely don’t. If this report was a lethal blow to the institution, so be it. God will raise up another institution.

<em>KN</em>: “So your failing is incompetence rather than cover up – your personal failing?”

<em>JW</em>: “Yes, incompetence; yes, alright. I’ll give you that one.”

If you are a victim the fact that you have had neither proper help, recognition or redress because of uselessness rather than mendacity, makes little difference. Archbishop Welby failed to act to expose the corruption that had polluted the Evangelical enterprise that he represented and was part of, and someone has finally accepted responsibility for the failure to do what needed to be done to bring it to light, acknowledge it and help those wounded by it.

One Anglican clergyman, the Revd Fergus Butler-Gallie, wrote to Archbishop Welby last week, putting the moral case at its most poignant.

“We will continue to pray for you, but I for one will be praying that you will resign. The damage you have done to this church will take a very long time to repair. More importantly, those things you did and failed to do inflicted such damage on people—made in the image of that same God—might never heal. Any healing of individuals or the institution must now be in His hands, not yours. The way you might serve that process best now is to resign. If you will not go for the love of the institution, if you will not go for the love of its people and priests, if you will not go for the victims, if you will not go for reasons of your own embarrassment or shame, then I pray you; for love of God, and Him alone, go.”

Mr Butler-Gallie's prayers have now been answered, and Archbishop Welby has stepped down "having sought the gracious permission of His Majesty The King". Whether his successor will usher in any kind of substantive change of culture in the higher echelons of the Church of England, remains to be seen.

<em>Archbishop Welby with Pope Francis in Rome, earlier this year. Photo by Filippo MONTEFORTE / AFP via Getty Images</em>