This year marks the 80th anniversary of the end of the Second World War. Victory in Europe and Japan occurred within months of the 80th anniversary of the end of the American Civil War in 1865. Had he not been assassinated, Abraham Lincoln would have been 65 years old when Winston Churchill was born in 1874, the same age as Churchill when he became prime minister of the UK in May 1940. These affinities are less important than the roles of these men in the wars that they fought.

Lincoln’s presidency and Churchill’s first stint as prime minister were entirely occupied with war. The Civil War began a few weeks after Lincoln took office, but the threat of secession and war had been made by some southern states as early as the presidential campaign. Lincoln’s assassination came only six days after the rebel states formally surrendered, but before all hostilities had ceased.

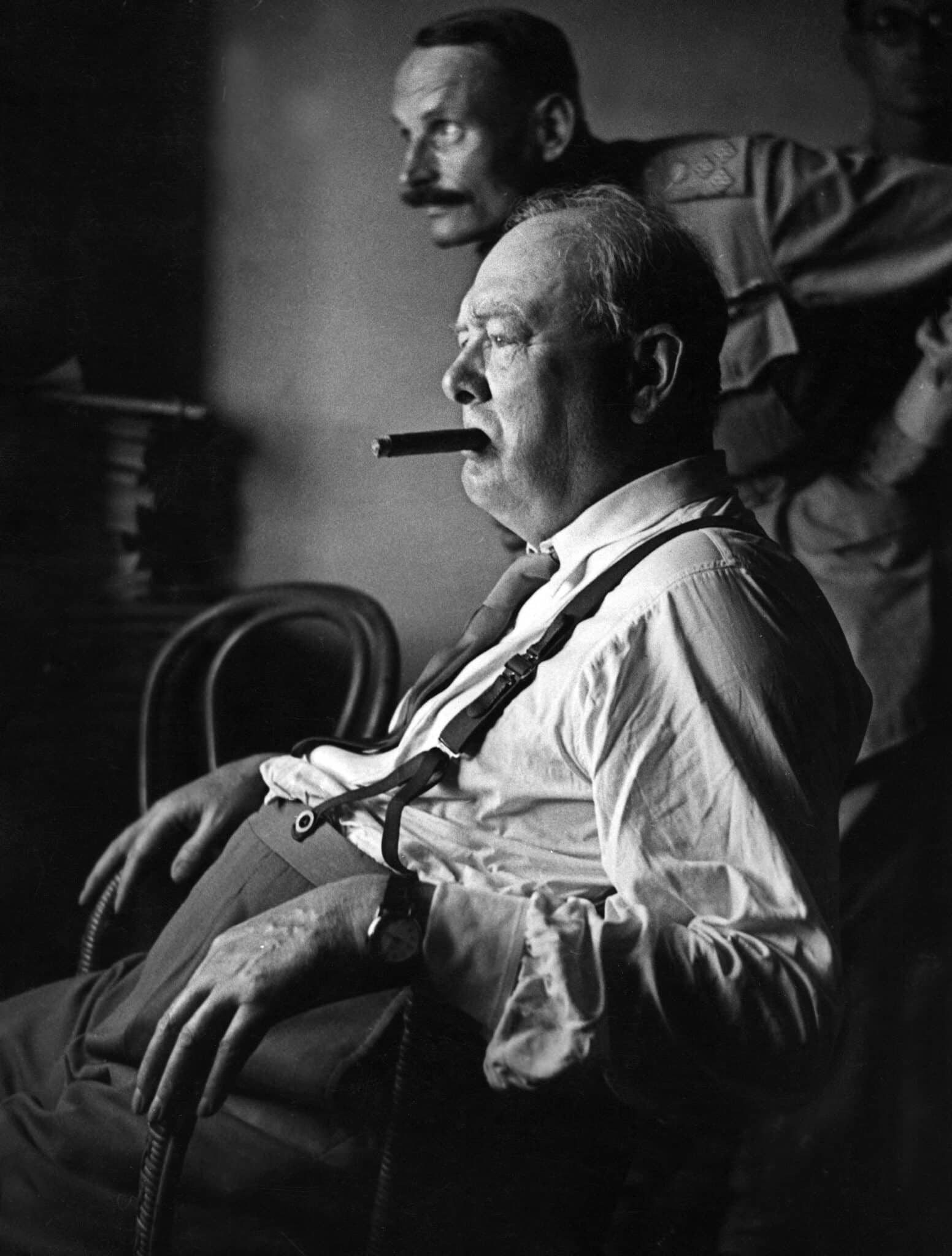

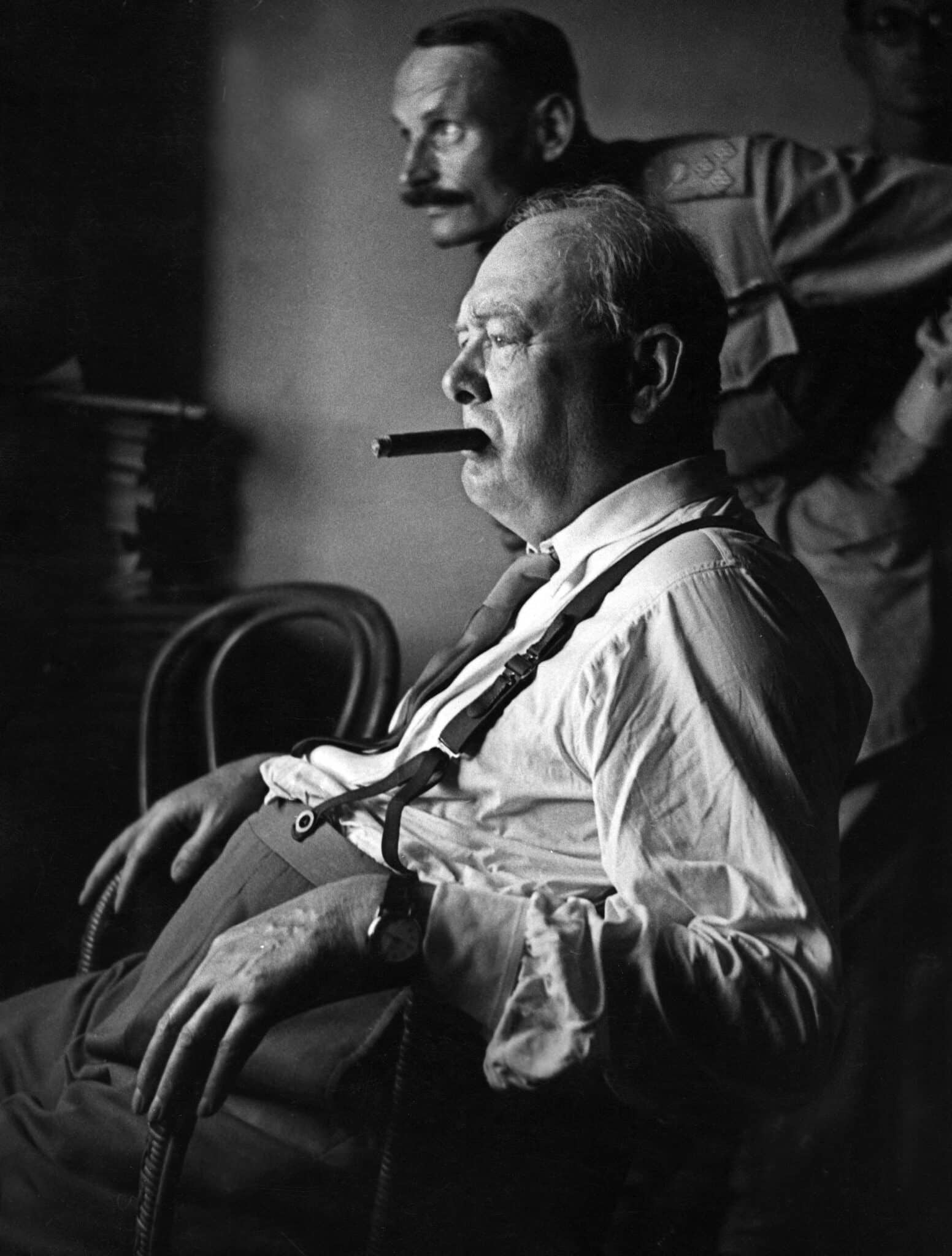

The Second World War was well under way when Churchill became prime minister; Germany invaded Belgium the day he took office, and France would fall a few weeks later. Lincoln died at the end of his war; Churchill was removed from office a few weeks after the end of his. It is not surprising, therefore, that the legacy of both is almost entirely related to the respective conflicts. Lincoln saved the Union, so the common wisdom goes, and Churchill saved Europe.

Two short speeches by these two great leaders deserve consideration in this 80th year since the end of the Second World War and 160 years after the end of the American Civil War. Lincoln’s brief second inaugural address on 4 March 1865 may be the most elegiac political speech in American history. Churchill’s announcement of Victory in Europe on 8 May 1945 is actually an amalgam of three speeches, first on the radio, then to a cheering audience from a Whitehall balcony, and finally in the House of Commons.

Symbolic of the issue that consumed every day of his presidency, Lincoln’s speech is dedicated solely to the hopeful end of the war, its causes, and a vision of post-bellum America. “The progress of our arms, upon which all else chiefly depends, is… reasonably satisfactory and encouraging,” Lincoln began. And while he would not be so rash as to predict the end of the war, which indeed ended about four weeks later, he harboured “high hopes for the future”.

Lincoln then moved on to an explanation for the causes of the war, which he reduced to slavery in the southern states. “All knew that this was… the cause of the war,” declared Lincoln. One party “would make war rather than let the nation survive, and the other would accept war rather than let it perish,” he claimed. Associating slavery as the war’s catalyst but saving the Union as his goal was one of his common tropes.

In a letter to newspaper publisher Horace Greeley in August 1862, Lincoln had infamously declared that his intention was to preserve the Union, neither to save nor destroy slavery.

“If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it,” he told Greeley. “What I do about slavery… I do because I believe it helps to save this Union.” Regardless of the causes and justification of the Civil War, Lincoln closed his second inaugural address on a note of reconciliation. “With malice toward none and charity for all,” he concluded, “let us strive… to bind up the nation’s wounds… to do all which may achieve… a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

Of course, the war in Europe was over when Churchill gave his VE Day speeches. His emphasis, other than a note about the continuing war with Japan, was one of victorious relief. After initially standing bravely alone against the enemy for more than a year, the British people should take solace in their ultimate victory, while expressing “gratitude to all our splendid Allies”. Churchill told the British nation: “This is your victory, victory of the cause of freedom in every land.”

Churchill also included a note of hope and reconciliation. “In the long years to come,” he said, “wherever the bird of freedom chirps in human hearts”, the world will “look back to what we have done” and say “‘do not despair, do not yield to violence and tyranny, march straight forward and die if need be – unconquered’”. But for now, Churchill concluded in a tone similar to Lincoln’s: “a terrible foe has been cast on the ground and awaits our judgment and mercy”.

Like Lincoln, Churchill is to be commended for the resolute witness both to the scourge of war and the resilience of those who fight on the side of justice and right. Eighty years separated the end of the American Civil War from the end of the Second World War, but we are still binding the wounds.

This article appeared in the June edition of the Catholic Herald. To subscribe to our award-winning, thought-provoking magazine and have independent, high-calibre, counter-cultural and orthodox Catholic journalism delivered to your door anywhere in the world click HERE.

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the end of the Second World War. Victory in Europe and Japan occurred within months of the 80th anniversary of the end of the American Civil War in 1865. Had he not been assassinated, Abraham Lincoln would have been 65 years old when Winston Churchill was born in 1874, the same age as Churchill when he became prime minister of the UK in May 1940. These affinities are less important than the roles of these men in the wars that they fought.

Lincoln’s presidency and Churchill’s first stint as prime minister were entirely occupied with war. The Civil War began a few weeks after Lincoln took office, but the threat of secession and war had been made by some southern states as early as the presidential campaign. Lincoln’s assassination came only six days after the rebel states formally surrendered, but before all hostilities had ceased.

The Second World War was well under way when Churchill became prime minister; Germany invaded Belgium the day he took office, and France would fall a few weeks later. Lincoln died at the end of his war; Churchill was removed from office a few weeks after the end of his. It is not surprising, therefore, that the legacy of both is almost entirely related to the respective conflicts. Lincoln saved the Union, so the common wisdom goes, and Churchill saved Europe.

Two short speeches by these two great leaders deserve consideration in this 80th year since the end of the Second World War and 160 years after the end of the American Civil War. Lincoln’s brief second inaugural address on 4 March 1865 may be the most elegiac political speech in American history. Churchill’s announcement of Victory in Europe on 8 May 1945 is actually an amalgam of three speeches, first on the radio, then to a cheering audience from a Whitehall balcony, and finally in the House of Commons.

Symbolic of the issue that consumed every day of his presidency, Lincoln’s speech is dedicated solely to the hopeful end of the war, its causes, and a vision of post-bellum America. “The progress of our arms, upon which all else chiefly depends, is… reasonably satisfactory and encouraging,” Lincoln began. And while he would not be so rash as to predict the end of the war, which indeed ended about four weeks later, he harboured “high hopes for the future”.

Lincoln then moved on to an explanation for the causes of the war, which he reduced to slavery in the southern states. “All knew that this was… the cause of the war,” declared Lincoln. One party “would make war rather than let the nation survive, and the other would accept war rather than let it perish,” he claimed. Associating slavery as the war’s catalyst but saving the Union as his goal was one of his common tropes.

In a letter to newspaper publisher Horace Greeley in August 1862, Lincoln had infamously declared that his intention was to preserve the Union, neither to save nor destroy slavery.

“If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it,” he told Greeley. “What I do about slavery… I do because I believe it helps to save this Union.” Regardless of the causes and justification of the Civil War, Lincoln closed his second inaugural address on a note of reconciliation. “With malice toward none and charity for all,” he concluded, “let us strive… to bind up the nation’s wounds… [and] to do all which may achieve… a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

Of course, the war in Europe was over when Churchill gave his VE Day speeches. His emphasis, other than a note about the continuing war with Japan, was one of victorious relief. After initially standing bravely alone against the enemy for more than a year, the British people should take solace in their ultimate victory, while expressing “gratitude to all our splendid Allies”. Churchill told the British nation: “This is your victory, victory of the cause of freedom in every land.”

Churchill also included a note of hope and reconciliation. “In the long years to come,” he said, “wherever the bird of freedom chirps in human hearts”, the world will “look back to what we have done” and say “‘do not despair, do not yield to violence and tyranny, march straight forward and die if need be – unconquered’”. But for now, Churchill concluded in a tone similar to Lincoln’s: “a terrible foe has been cast on the ground and awaits our judgment and mercy”.

Like Lincoln, Churchill is to be commended for the resolute witness both to the scourge of war and the resilience of those who fight on the side of justice and right. Eighty years separated the end of the American Civil War from the end of the Second World War, but we are still binding the wounds.

<strong>This article appeared in the June edition of the <em>Catholic Herald</em>. To subscribe to our award-winning, thought-provoking magazine and have independent, high-calibre, counter-cultural and orthodox Catholic journalism delivered to your door anywhere in the world click <a href="https://catholicherald.co.uk/subscribe/?swcfpc=1"><mark>HERE</mark></a></strong>.