The historic low of England and Wales’ current fertility rate is often aestheticised, or even glamorised, through the childfree and DINK, Double Income No Kids, lifestyle on social media. TikTok and Instagram overflow with images of perfectly curated interiors, long haul holidays, and leisurely mornings untouched by responsibility. In an age of high rents and mortgage rates, expensive childcare, and economic uncertainty, this narrative lands easily in our ever growing secular society. It also offers a flattering explanation for a painful reality many people find themselves in, childless either by circumstance or by choice. To admit that the majority of us long for marriage and children can feel naive or needy, so we as a society tell ourselves a different story, that independence is superior, that children are optional additions, and that the nuclear family is an outdated ideal.

When family life is consistently framed as restrictive, environmentally irresponsible, or incompatible with fulfilment or ambition, it becomes harder for people to pursue it with confidence. The rise of explicitly anti natalist movements online, especially those arguing that bringing children into the world is morally wrong, pushes this logic to its extreme. Children are no longer seen as gifts, but as liabilities.

Fear also plays a powerful role in shaping this hesitation. Many people openly say they do not want children because they are afraid, afraid of climate catastrophe, rising crime, political instability, and economic fragility. They are told repeatedly that the world is burning, society is unsafe, and that bringing a child into such conditions is irresponsible, or even selfish. This narrative inevitably produces a culture reluctant to imagine, or invest in, a hopeful future.

This is not something that should be affirmed or dressed up as moral progress. It is a collective failure. If people do not feel safe, supported, or hopeful enough to welcome children, then the task before us is not to celebrate childlessness, but to rebuild the conditions, social, economic, and spiritual, that make family life feel possible and aspirational again.

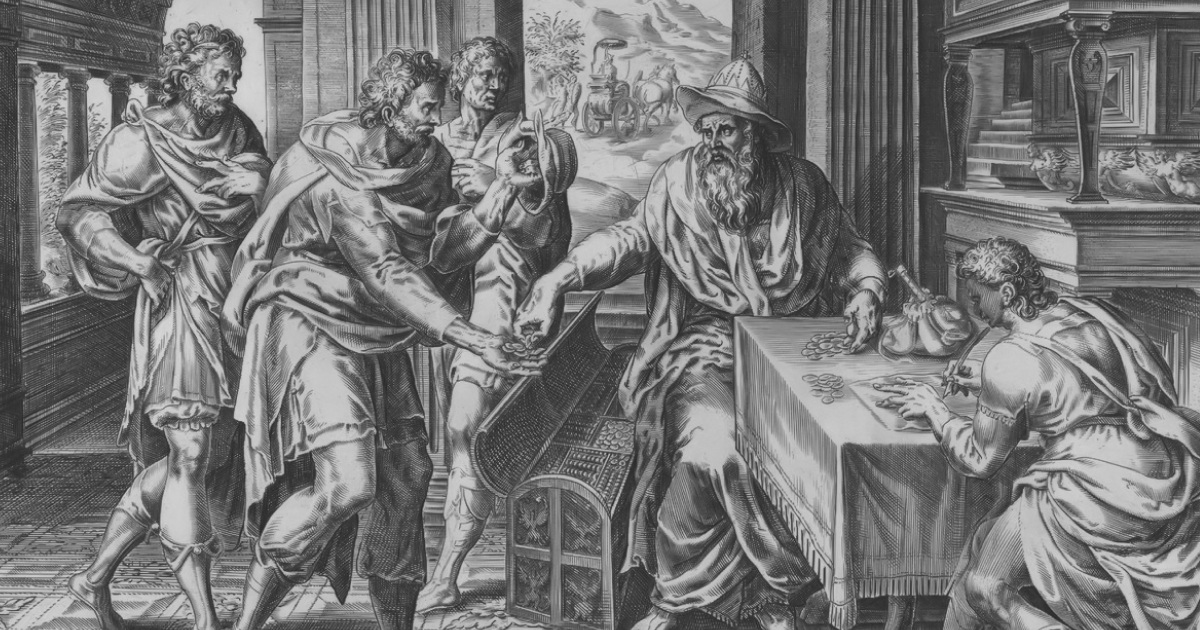

Today’s anti life mentality is spiritually familiar. History’s first response to Christ, after all, was violence against children. When we look at the Holy Innocents, we see they were massacred by Herod under the brutal reasoning of neutralising potential rival threats in order to preserve his comfort and control. In other words, unpredictability had to be eliminated in the name of self protection.

The Holy Family, meanwhile, offers a radically different vision. Mary and Joseph did not build a life around personal freedom or comfort. They welcomed a child at great cost. Their family was poor, precarious, and repeatedly displaced. And yet the Church presents Nazareth not as a cautionary tale, but as the model of human flourishing, because love, sacrifice, and service, not autonomy, are the true foundations of joy.

Catholic anthropology insists that we are made for self gift. Children are not obstacles to meaning, but one of its clearest expressions. Scripture does not romanticise parenting, but it consistently names children as a blessing from God, not a mistake to be managed.

Thankfully, Gen Z seems less convinced by the anti family script. While they are acutely aware of narratives around climate change, violence, and economic instability, many resist the conclusion that the answer is to opt out of parenthood altogether. Many are surprisingly open on social media about wanting marriage, children, and stability. Actress Millie Bobby Brown, 21, best known for playing Eleven in Stranger Things, married Jake Bongiovi, the son of Jon Bon Jovi, in 2024, and the couple adopted a baby girl this year. She has spoken openly about her long held desire for marriage and motherhood, sparking a range of reactions, some supportive, others critical, particularly claims that she is too young to want these things.

The negative responses are unsurprising. The sexual revolution of the 1960s reshaped marriage and family life, often at a cost, leaving many childless by circumstance. An unhealthy dating culture, contraception that has uncoupled sex from love, marriage, and procreation, and the rise of the internet have all contributed to a more isolated and individualistic society. Many carry profound grief in this area, made all the heavier by a culture that belittles family life and children.

But we do ourselves no favours by pretending that a society structurally hostile to marriage and family life is merely the result of personal choice or progress. If we are serious about supporting families, the response must be both cultural and practical. That means economic policies that make raising children feasible, workplaces that respect parenthood, parishes that actively welcome families, and intentional efforts to help single people form meaningful connections and discern their God given vocations. And perhaps most importantly, it requires renewed moral confidence to say that marriage, children, and lifelong commitment are not oppressive ideals, but human goods.

This Christmastide, let us reject Herod’s ruthless cull and the DINK avoidance of responsibility, and instead echo the Holy Family’s fiat by restoring the value of family life in our communities, both online and in person.