In his poignant poem "Norfolk", John Betjeman uses memories of childhood holidays with his father to reflect on the loss of innocence. He looks back on "the rapturous ignorance of long ago / The peace, before the dreadful daylight starts / Of unkept promises and broken hearts." T. S. Eliot also approached a similar theme, of regret and the struggle to come to terms with the past, in "Burnt Norton", from his Four Quartets.

"Footfalls echo in the memory / Down the passage which we did not take / Towards the door we never opened". In "East Coker", the second of the quartets, he notes that "As we grow older / The world becomes stranger, the pattern more complicated".

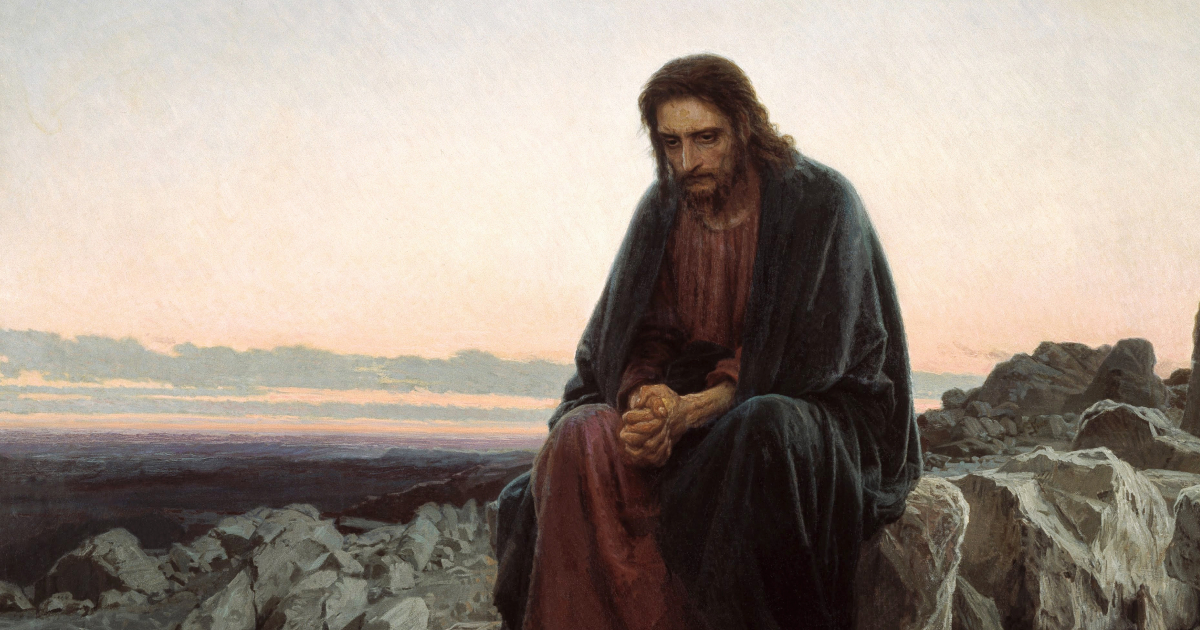

As Christmas approaches, I often return to these poems. I am old enough now to have accumulated plenty of regrets of my own, and a keen awareness of my failings and weaknesses. I know viscerally what the General Confession in the Book of Common Prayer means when it says that the remembrance of our sins is grievous unto us. But the fundamental simplicity of the Christmas message — that God entered the world as one of us, to bring light to our darkness and give us a way home — offers a remedy for all the knots in which we humans tie ourselves.

Amid the difficulties of adult life, all the compromises and frustrations, all the responsibilities and worries, when we turn our attention once more towards the boy in the manger, we have an opportunity to recapture just a little of the wonder we felt at those childhood Christmases long ago. We can let go of cynicism and weariness, and embrace, for a few days, the sense of delight.

There is good precedent for such an approach. Our Lord himself said that to enter the Kingdom of Heaven we must become like little children. On the face of it, this is an odd thing to say. In worldly terms, it is adulthood that gives us access to full understanding, to a clear knowledge of the truth of things. To be immature is to refuse to develop appropriately. St Paul himself uses the metaphor of putting away childish things to illustrate the future transition of the Christian believer from this earthly life into the divine life with God. However, what Jesus is getting at in Matthew’s Gospel is the importance of humility and trust. The spur for his remark about the Kingdom is a question from the disciples about heavenly hierarchies — a subject which they bring up with almost comical frequency — and the point about children in this context is that they are yet to acquire the pride in one's own position and keen awareness of social hierarchy with which we adults are so frequently preoccupied.

The democratic instincts of small children are fascinating. When my son was a toddler, we would walk in the park near our home, and there was a particular gentleman of the road we would see on a regular basis, sitting on a bench drinking cheap beer. He would normally say hello, and my son would return the greeting with a smile, as he would with anyone else.

About the homeless, it often reminds me of a beautiful scene from C. S. Lewis's The Great Divorce, where a woman who lived a very ordinary but very saintly life, Sarah Smith of Golders Green, is paid high honours in heaven, attended by angels and suffused with light.

The essential straightforwardness of Christianity is, or ought to be, one of the most attractive things about the faith. Certainly, it is also full of depth and strangeness and texture. The Bible and the teaching documents of the Church are not always immediately intelligible. Great inquiring minds have devoted their lives to understanding and articulating the detail of doctrine. In our own time, the Church may yet turn out to be the last redoubt of serious learning and scholarship in a world where ideology, technology and moral revolution are combining to undermine the integrity and meaning of the humanities.

Nevertheless, when Jesus is asked what people must do to be saved, time and again he reiterates the basics. Repent and believe, amend your life, forgive your enemies, and give generously. As the Prophet Micah has it, “what doth the Lord require of thee, but to do justly, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with thy God?”

The challenge, of course, is to keep these core imperatives in our minds and hearts not just for a few days at the end of December, but for the entire year. My mother likes to quote an aphorism to the effect that Christmas is not a date, but a state of mind. Cynics might call it twee or sentimental — but it is not the time of year for listening to cynics.