On 16 February 1946 – 80 years ago today – Clare Boothe Luce was received into the Catholic Church. At 42, she had already been an actress, editor, playwright and congresswoman, and was married to America’s most prominent publishing tycoon, Henry Luce. Her conversion was front-page news.

Her friend Gore Vidal – no mean critic – described her as “a Dresden doll, only unbreakable”. He thought she could have been president. As the New York Times put it in their obituary: “She had enough careers to satisfy the ambitions of several women, but none tied her down for long.” Such a life should attract (but often does not) a gifted biographer, and Mrs Luce was fortunate in authorising Sylvia Jukes Morris to do so. The result was an astonishing 1,300 pages over two volumes – Rage for Fame (1997) and Price of Fame (2014) – meticulous, clear-eyed, affectionate yet not uncritical.

She had had a grim start: born Ann Clare Boothe in insalubrious West 125th Street, New York City, on March 10, 1903, the illegitimate daughter of a pit orchestra violinist and patent-medicine salesman and an ambitious mother, a former chorus girl. As a child she understudied Mary Pickford; as an adolescent she campaigned for equal rights with the suffragist Alice Paul; as a 20-year-old she wed the alcoholic, abusive and much older clothing heir George Tuttle Brokaw. They had a daughter, Ann, in 1924 and divorced after six years.

The divorce settlement made her rich and able to match her ambitions. She persuaded Condé Nast to give her a job at Vogue; she became managing editor of Vanity Fair; and the author of two books and four Broadway plays – including her strangely misogynistic The Women, which earned her millions. When she met George Bernard Shaw, the playwright who inspired her, she said: “Except for you, I wouldn’t be here.” Shaw quipped: “And now, let me see, dear child, what was your mother’s name?”

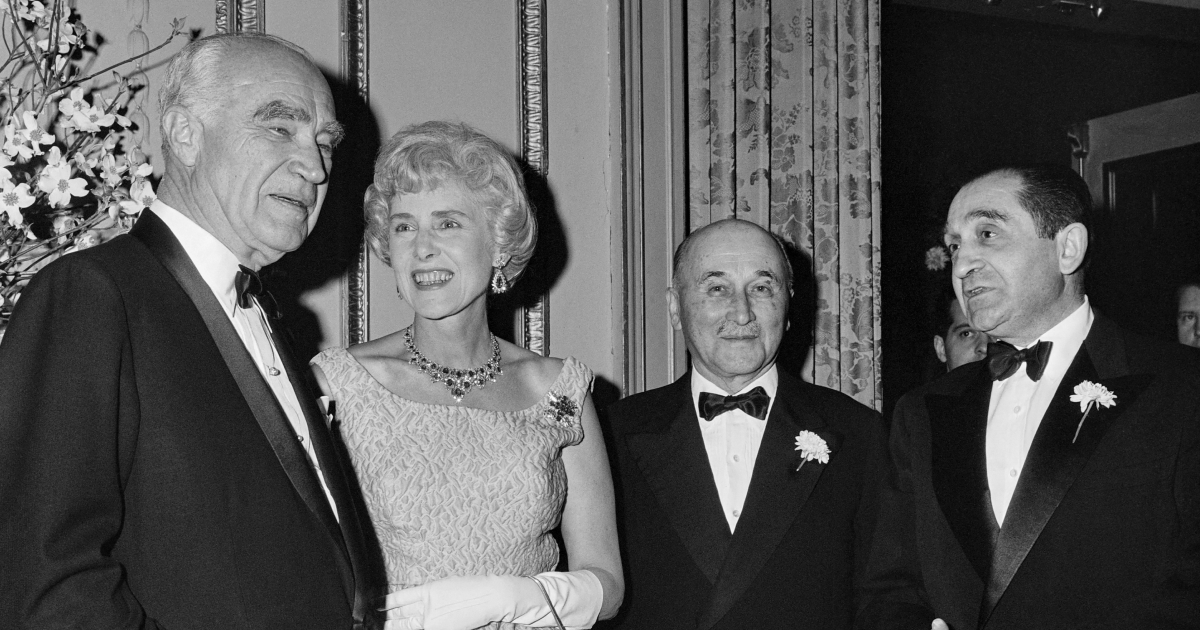

In 1934 she met Henry (“Harry”) Luce, co-founder and editor-in-chief of Time Inc. It was a coup de foudre. They married in November 1935. It proved to be a powerful union that lasted until his death, despite their differences, affairs and separate careers. She worked as a war correspondent for Harry’s Life magazine in 1939 and 1940 and, when she produced Europe in the Spring (1940), Dorothy Parker suggested another title: “All Clare on the Western Front”. Having turned on Franklin Delano Roosevelt, she became, and remained, steadfastly Republican. In 1942 she was elected Connecticut’s first congresswoman.

In January 1944 Clare was walking down a street in San Francisco with her 19-year-old daughter, Ann, and when they passed a small Catholic church Ann suggested they go in. They entered and stayed through Mass.

The following morning Ann died in a freak car accident near the Stanford campus, where she was attending college. On hearing the news Clare rushed to the church where she had attended Mass the previous day. She spent half an hour there and returned to her hotel in tears.

A few hours later she asked her secretary to call for the priest of the church she had just visited. The bewildered cleric, whose answers to Clare’s questions she found “too pat, too shallow”, was swiftly dismissed. She did not pursue her quest but buried herself in her congressional campaign with her customary vigour and was re-elected.

A year later, in a night of anguish, Clare opened a letter from an intermittent correspondent, Fr Edward Wiatrak SJ, who had referred to an extract from the Confessions of St Augustine which resonated with her. She called Fr Wiatrak, who answered at 2am. “This is the call we have been praying for. You think you have intellectual deficits. They are spiritual, of course.”

He referred her to the evangelist Mgr Fulton Sheen, whose golden-voiced baritone had been swaying and soothing American souls since 1930 through his radio programme The Catholic Hour. Jukes Morris describes him as immaculately cassocked, with prominent blue eyes under thick eyebrows and a warm smile, as comfortable in sophisticated society as he was in the pulpit. Only last week the Vatican announced that Archbishop Sheen, as he became, is to be beatified.

Clare had always considered herself an Episcopalian, although her mother was Lutheran and her father Baptist. She met the monsignor the next day. Before he had spoken for three minutes Clare demanded: “Listen, if God is good, why did He take my daughter?” The Right Reverend shot back: “In order that you might be here in the faith.”

For his part, he marvelled at her intuitiveness, describing “her mind like a rapier; bursting foibles in a second”. She also read deeply and wisely as her instruction continued.

After five months of intense discussion and argument – the longest period the monsignor ever undertook – Clare was baptised by him in a side chapel of St Patrick’s Cathedral, New York. Giving God and his student the credit, he observed: “No man could go to Clare and argue her into the faith. Heaven had to knock her over.” His mission achieved, Mgr Sheen chose Fr Wilfrid Thibodeau, a priest of the French Fathers of the Blessed Sacrament in Lexington Avenue, as Clare’s confessor.

The son of Presbyterian missionaries, Harry was confused and appalled and did not attend his wife’s Baptism, although in time he became reconciled to it and would even occasionally accompany Clare to Mass.

Even her Catholic friend Jack Kennedy wrote: “You’re still young, my God. Why strap the cross on your back? I never thought the Catholic religion made much sense for anyone with brains.”

Fifteen years later she received a call from his father, Joseph Kennedy Sr, a former lover, who was agitated by the “swarms of nuns settling in the front seats” of Jack’s campaign rallies, “clicking their rosaries and their dentures”. He pleaded with Clare to intervene with Cardinal Spellman. “[He] hates me. I beat him out of some real estate. But you could tell him, tactfully, that if he wants a Catholic in the White House, he’d better keep those… nuns from hogging all the front rows. This isn’t an ordination. It’s an election!”

Despite the bigotry that then divided many American Christians, Clare’s conversion did nothing to dent her popularity. Later in 1946 she was named in a poll as the second most admired woman in America, after Eleanor Roosevelt. She also managed to appear in the US Ten Best Dressed list and to be hailed as having “the second-best pair of legs in America”.

Mass became a daily ritual and she was soon among the country’s most prominent and eloquent converts. In 1947 she wrote a three-part article for McCall’s magazine, “The Real Reason”, explaining her conversion. In 1949 she received an Oscar nomination for her original story for the gentle comedy Come to the Stable, about two nuns setting up a hospital for children. In 1951 she received the Cardinal Newman Award, which must have pleased the monsignor, a devotee of the cardinal.

In 1952 she edited Saints for Now, a collection of essays by famous authors who, of course, also happened to be friends. Evelyn Waugh chose the Empress Helena; Rebecca West, St Augustine; Wyndham Lewis, Pius VI; Whittaker Chambers, St Benedict. Writing in the New York Review of Books, Francine du Plessix Gray noted: “But a still more striking aspect of the book is Mrs Luce’s pious introduction. The saint for whom she expresses the greatest affection in these pages is that most self-effacing of all Catholic role models, St Thérèse of Lisieux. ‘Hidden from the world in a Carmelite monastery, … Thérèse seeks to become little and helpless and hidden, like the infant Divinity.’”

“The ‘little’ Thérèse, paragon of anonymity, patron saint of anti-celebrity, is a curious choice for a woman who achieved a greater degree of fame than almost any other woman of her generation …”

In early 1953 Clare became the US ambassador to Italy, appointed by Eisenhower and confirmed by the Senate – although her Catholicism was a point of contention. Would she try to engage or conspire with the Pope? This she could easily deflect, as she was not accredited to the Vatican – the United States would have no Personal Representative of the President between 1951 and 1984.

According to Jukes Morris, while her religious fervour had faded by the time she was appointed to Rome, she and Harry remained close to the Jesuit Fr John Courtney Murray, who had succeeded Fr Thibodeau as her confessor.

In her three-and-a-half years, “La Luce” acquitted herself with distinction and style in Rome, although her time there was almost overshadowed by suggestions that she was being poisoned. It proved not to be a communist plot but merely arsenate dust from the lead paint in the rosetted ceiling of her bedroom at the Villa Taverna. “Arsenic and Old Luce,” read one headline.

After Harry’s death in 1967 she retreated for some years to Honolulu, though fitfully. Washington remained a draw. Her last significant government appointment would be – at the urging of Henry Kissinger – to the prestigious President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board in 1973. She was reappointed by President Reagan in 1981. She had been campaigning for Republican presidential contenders since Wendell Wilkie in 1940.

Time magazine’s obituary observed: “The elder stateswoman held court among young Republicans as a kind of inspirational eminence, an unmistakable figure at every conservative function, silver-haired, bright-eyed, dripping pearls and epigrams.” She was once described as “a beautiful palace without central heating” – she would always endure this sort of stick. In short, she was a phenomenon.

She died, aged 84, on October 9, 1987, on what would become the Feast of St John Henry Newman.

Among the last visitors to her Washington apartment was Fr Christian of Mepkin Abbey in South Carolina, once a plantation and a house with happy memories given by Clare and Harry to the Trappists. Clare had not been to church much in recent years but, when the priest robed and offered her Confession, Communion and Extreme Unction, she said: “I want them all.”

As Marie Brenner reported in a profile for Vanity Fair in March 1988, Clare was buried near Harry and her mother in the shadow of a great oak and “an immense white-granite cross, in the small grove where she had walked so many times, staring at her daughter’s headstone or off into the distance at the Cooper River, where Irish immigrants had once toiled building a dike for twenty-five cents a day. The Trappists performed the ceremony with their characteristic austerity: no organ, just a simple guitar. Mrs Luce was laid out not in a bronze coffin but in a varnished pine box.”