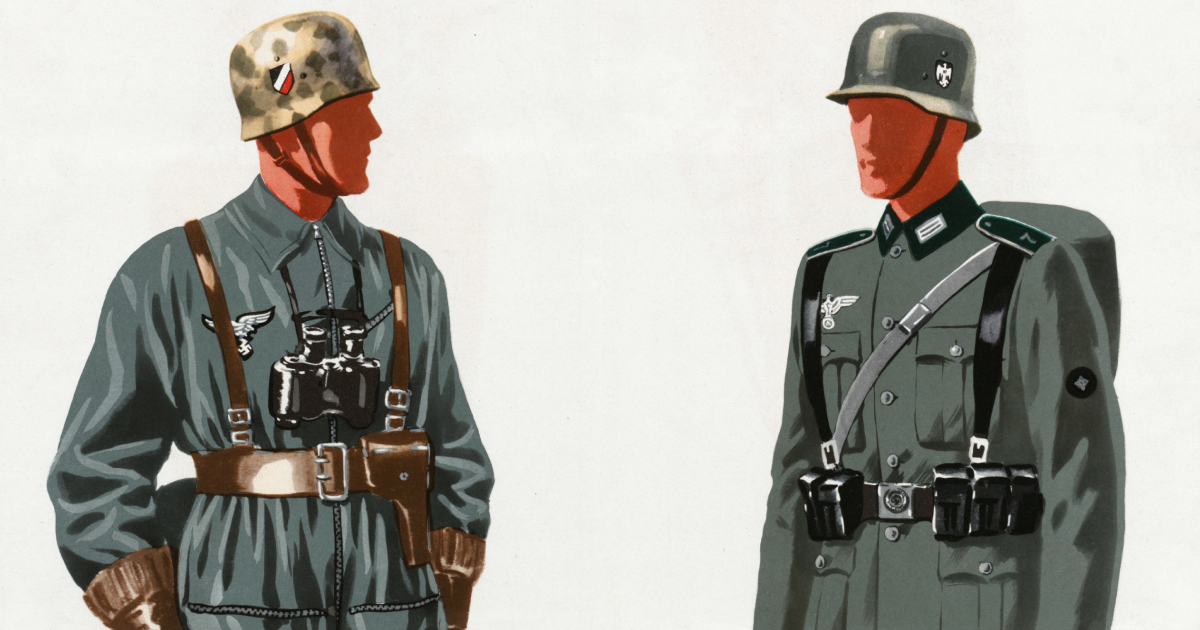

In a recent episode of Scott Hahn’s The Road to Emmaus podcast, Fr Gregory Pine OP defended the position that it is never permissible to lie. The two presenters briefly discussed the popular hypothetical involving a Gestapo officer showing up at your door during the Second World War. You are hiding several Jews in your basement, and the officer asks you point blank if this is the case. What should you do?

In the podcast discussion, Fr Pine articulated his view that in this situation your only moral recourse is to try to use evasive language “in an artful way”. Here Fr Pine follows St Augustine and St Thomas Aquinas in arguing that in normal speech, that is, speech not involving joking, hyperbole, metaphor or the like, it is never acceptable to tell a deliberate falsehood, even if doing so might save a person’s life. According to Pine, therefore, the decision to falsely tell the Gestapo, “No, sir, there aren’t any Jews in this house,” would constitute a venial sin.

While I am very grateful to Fr Pine for his ministry, I think he is mistaken on this question. But first we should clarify our terms. The proposition “lying is always wrong” is one with which all Catholics must agree, for the simple reason that lying is, by definition, a sinful form of speech. The Catechism states: “Lying is the most direct offense against the truth. To lie is to speak or act against the truth in order to lead someone into error” (2483).

The question before us, then, is not whether it is ever permissible to lie to the Gestapo officer, it is not. Rather, the relevant question is this: does speaking a deliberate falsehood to the Gestapo officer count as lying? In other words, we want to know whether speaking in this way constitutes an offence against the truth in the manner proscribed by the Catechism.

While I am always reluctant to contradict such theological heavyweights as St Augustine and St Thomas, I think a strong case can be made that the position defended by Fr Pine is untenable. This case rests on three separate lines of evidence.

First, Fr Pine’s view contradicts our moral intuitions. It is not plausible to say that you are duty-bound to mislead the Gestapo officer through verbal gymnastics, but that the moment you state something factually untrue, you fall into sin. Similarly, the operation of spies during wartime strikes most of us as a legitimate enterprise, yet spies are routinely required to say things that are not true if they wish to avoid capture.

Second, Fr Pine’s view contradicts the testimony of Sacred Scripture. When the king of Egypt challenges the Hebrew midwives, Shiphrah and Puah, over their failure to kill the Hebrew baby boys, the midwives respond with deliberate falsehoods. In the very next verse we are told: “So God dealt well with the midwives” (Exod 1:20). Fr Pine attempts to interpret this as God endorsing the midwives’ commitment to justice rather than their dissemblance. But that is not what the text says or implies; the more straightforward reading is that God approved of their use of falsehood in the protection of human life.

Rahab is another example of a biblical figure praised in both the Old and New Testaments for helping to save the Israelite spies, even though she does so by telling a fabricated story to the king of Jericho (see Jos 2:1–6; 6:25; cf. Heb 11:31; Jas 2:25). A third example comes from the Book of Tobit, when the archangel Raphael says to Tobit, “I am Azari′as the son of the great Anani′as, one of your relatives” (5:12). This appears to be a clear case of someone being justified in stating a deliberate falsehood for a higher purpose.

Third, Fr Pine’s view contradicts the witness of Christian tradition. Perhaps the most notable examples come from the English recusant era, when Protestant authorities were actively hunting, torturing and executing Catholic priests. During this period, English Jesuits developed a theory of “equivocation”, whereby one could, in dire circumstances, deliberately tell an untruth while making a mental reservation.

For example, if a local sheriff arrested a Catholic servant and demanded to know whether any priests were being harboured in his master’s house, the servant could legitimately reply, “There are no priests in my master’s house …” while silently adding the mental reservation “… who are below the age of 30.” In this way, the servant could verbally mislead the authorities while avoiding a mental commitment to a false proposition.

While this approach may sound fanciful to some, it appears to have been practised routinely by many of the heroic Jesuit priests and laybrothers responsible for keeping the flame of faith alive in England. Fr John Gerard SJ, for instance, often assumed the disguise of a wealthy gentleman during his travels up and down the country, which presumably required him to invent stories about his occupation, hometown and so forth. Likewise, when St Nicholas Owen was captured and tortured on the rack, he seems to have denied any knowledge of the Jesuit superior Fr Henry Garnet SJ, despite having served him for many years.

In addition to these examples from tradition, we also have the case of the Venerable Salvo D’Acquisto, who appears to have confessed to a crime he did not commit in order to save more than twenty civilians from execution by the Nazis.

It can therefore be said that Fr Pine’s position on lying is, despite its impressive pedigree, unrealistic and ultimately mistaken. Even so, the interested reader should follow Fr Pine’s recommendation to consult Stewart Clem’s recent book Lying and Truthfulness: A Thomistic Perspective. While doing so, one might also consider Fr Pine’s own recent book, Training the Tongue and Growing Beyond Sins of Speech.