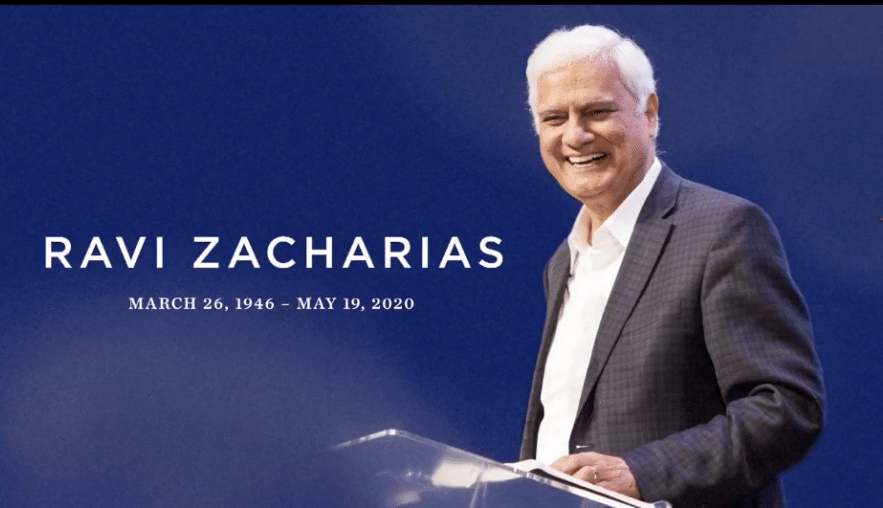

Ravi Zacharias, who died in May of last year, was American Evangelicalism’s superstar apologist. The movement’s flagship magazine, Christianity Today, headlined their recent report on him, “Ravi Zacharias Hid Hundreds of Pictures of Women, Abuse During Massages, and a Rape Allegation.” The story is worse than that. Southern Baptist leader Russell Moore called it “a pattern of predation that can only be described as criminal, sociopathic, and, indeed, satanic.”

Yet, and this is important, he seems to have been an extraordinary man. The people speaking of him in his memorial service speak of his kindness, humility, generosity, and his love of God and man. People I know and trust admired him. And yet. Who knows if he was brilliant at playing a role or managed to be two completely different men. In either case, you can see why the revelation was so traumatic for American Evangelicalism.

Already Exposed

Zacharias had been exposed already, though, by a married woman who said he’d “groomed her.” He even promised Lori Ann Thompson he’d kill himself if she told her husband. She did expose the online affair and Zacharias fought back. Conservative journalist David French, himself an Evangelical and a friend of some of the people involved, tells the story.

Predictably, in French’s telling, the senior people in Zacharias’s ministry RZIM, a very large international affair, did not pursue the charges very hard and enabled the abuse to continue. At a crisis point, RZIM’s anonymous (yes, anonymous) board of directors lied to its employees.

They claimed to have thoroughly investigated the matter, when they hadn’t, and presented Thompson as the predator and Zacharias as her innocent victim. Zacharias got away with it partly by refusing to give up his old phones, which as it turned out contained damning evidence. That should have been a very big red flag. His board let him withhold them, and exonerated him without ever seeing what they had to know was crucial evidence. This suggests they had some idea what they might find.

A Catholic can’t gloat or point fingers. Everything Zacharias and his enablers did has been done by Catholic priests and bishops many times over. We have our recent example in the exposure, also after his death, of the widely-sainted Jean Vanier. The cases are uncomfortably similar. He and Zacharias both spiritualized their abuse, trying to make their victims feel that they met God through their sexual intimacy.

The Problem and the Lesson

But here’s the problem and the lesson. Even before Thompson exposed Zacharias, the world and his people had evidence that he couldn’t be trusted. And his people buried the story by waving it away, and depending on Zacharias’s fans to minimize it if they cared about it at all. A few years ago, he was exposed for inventing academic credentials, including being “a visiting scholar at Cambridge University” and both “a professor” and “a senior research fellow” at Oxford University. Neither was remotely true.

Not surprisingly, the news didn’t seem to bother many Evangelicals. In one discussion I saw, an Evangelical scholar I like and respect tried hard to deflect the criticism. What’s the point? he asked. Zacharias does great work. He argues with hostile secularists in their own institutions and wins. So what if he “inflated” his credentials? We Christians criticize each other too much. The article was essentially an attempt to tear him down.

We can all understand this. If someone accused one of my heroes of inventing a self-serving history, I’d want to deny it too. I'd look for excuses. Accepting the truth would take great effort.

Like so many of his peers, the scholar accepted the charges, but denied they meant anything. If a student at his college were discovered to have invented a high school degree when he’d flunked out junior year, no matter how smart he was, I’m sure this scholar would have agreed with his being expelled. But not Zacharias. Zacharias was a star. He was a celebrity, a leader, someone his movement needed.

He was an Evangelical prince.

The Lessons

French draws some lessons about this. We should never say that we know the man and he would never do that, he says. He’s right, sadly. We would like to, but we can’t. That’s a hard lesson. You feel sour, cynical, uncharitable, especially when respectable people circle round the accused, as they always do. But we know, now, from example after example, that things are not always what they seem. We know that spiritual leaders can lead two different lives, and the public life may give no hint at all of the other one.

French warns against trying to protect the accused from disgrace. “The goal of any organization facing claims of abuse should be discerning truth, not discrediting accusers. All accusers should be treated immediately — publicly and privately — with dignity and respect.” Because they might well be telling the truth.

We need to account for the way Christian ministries work. The people who run them have reasons not to question the leader. They “derive not just their paychecks but also their own public reputations from their affiliation with the famous founder.” They share his admiration and influence, and they lose it if he falls. “There is powerful personal incentive to circle the wagons and to defend the ministry, even when that defense destroys lives.”

Being a ministry or apostolate brings its own temptations and very useful rationalizations. “The zeal to protect the leader and punish or discredit the accuser can also rest in a particular brand of arrogance,” French writes. He gives examples of lines like: “My ministry is necessary”; “Souls are at stake”; and “Look at all the good we’re doing,” all of which Zacharias and his enablers used.

God and the Prince

French points to a truth we tend to forget. We believe the opposite, that God needs us, and that justifies hiding our own sins and covering up others'. “In reality," he writes, "God will accomplish His purposes, with or without any of us, regardless of our gifts or talents.”

I would go back before the discovery that he abused women to the discovery that he'd invented credentials. Something should have been done then. The lesson the disastrous Zacharias affair teaches is the one we tend to apply solely to political figures, though it applies to anyone who gains great power: Put not your trust in princes.

Do not treat them differently (St. James speaks against this rather firmly in the second chapter of his epistle). When you have the evidence that the prince has broken the law, no matter how being convicted will hurt his rule, convict. The penalty may be light or heavy, depending on what justice and mercy require.

You may save him from himself, and you may save others from him. He can always repent and get his life back, and perhaps his ministry. But only if you convict.