The papal visit to Georgia has left us with a stark image of just how far off Catholic-Orthodox unity remains. Last Saturday, the Holy Father celebrated Mass in a stadium in the capital, Tbilisi. Instead of the usual rapturous throng, there were thousands of empty seats. The bishops of the Georgian Orthodox Church had chosen not to attend and their flock had followed suit. The Georgian Church’s website explained that “as long as there are dogmatic differences between our churches, Orthodox believers will not participate in their prayers”.

The snub came days after a breakthrough agreement between Catholic and Orthodox theologians. They had gathered in the Italian town of Chieti to discuss two highly contentious issues: papal primacy and the synodal structure of the Church. They concluded that for the first 1,000 years of Christian history, believers in the East and West had a similar understanding of primacy and “synodality”.

Writing at catholicherald.co.uk, Fr Mark Drew said the Chieti agreement was, if anything, a vindication for the Orthodox. “The document has accepted a reading of the first millennium which is more in tune with the way Orthodoxy has tended to see it than that favoured by Catholic apologetics until recent times,” he wrote. Nevertheless, one Orthodox community dissented from the agreement: the Georgian Orthodox Church.

This wasn’t the first time that the Georgian Orthodox have rejected a broad theological consensus. The Church, which represents some 3.6 million of the world’s 217 million Orthodox Christians, pulled out of the historic Pan-Orthodox Council in June. It had objected to several council documents, especially “The Relation of the Orthodox Church with the Rest of the Christian World”.

It is tempting to dismiss Georgian Orthodox leaders as throwbacks to an anti-ecumenical age, but they serve a useful purpose. They remind us that, despite major theological advances, Catholics and Orthodox believers remain deeply estranged in many parts of the world. They also demonstrate that the Orthodox Church is not monolithic, but rather a complex and unstable grouping of fiercely independent churches.

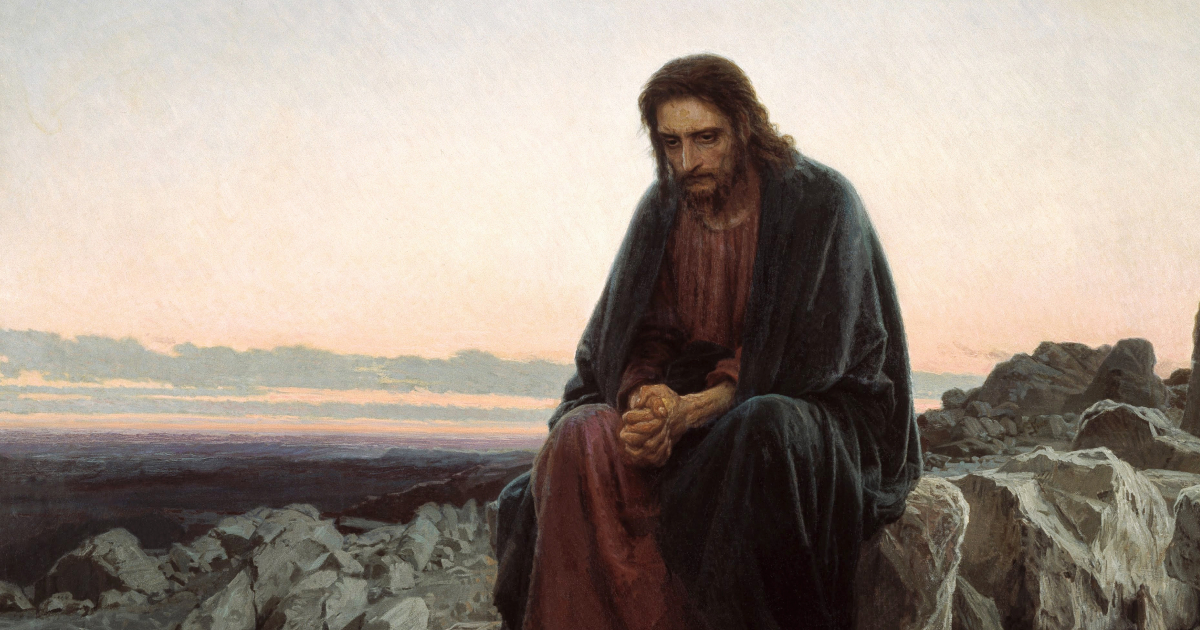

Pope Francis knows this well, of course. He recognises that Catholic-Orthodox reunion will, in all probability, take centuries. That is why the Georgian Orthodox snub is unlikely to trouble him: it is only a minor setback on a journey desired by Christ himself.

During his Georgia trip, Francis visited the country’s spiritual capital, Mtskheta, where he spoke movingly of the “unity which comes from above”. Standing in the spot where Christianity took root in the 4th century, he venerated the sacred tunic, regarded by the Georgian Orthodox as Christ’s seamless garment. The relic, he said, “exhorts us to feel deep pain over the historical divisions which have arisen among Christians: these are the true and real lacerations that wound the Lord’s flesh”.

While Francis has a holy impatience with Christian divisions, he knows that unity won’t come from human effort alone; ultimately, it is a gift “from above”. For now, we are faced with empty seats, but there may come a day, long after we are gone, when Catholics and Orthodox Christians will worship side by side.

Peace, but not at any price

By a narrow majority the people of Colombia have, in a national referendum, rejected the peace agreement that their government has negotiated with the Farc rebels, who for more than half a century have waged war against the state, and in the process have been responsible for thousands of civilian deaths.

Given the intricate nature of the negotiations with Farc, the time spent on them and the high hopes that peace and stability were at last coming to Colombia, this seems like a grave setback.

But there are lessons to be learned from the result. First of all, no one has voted for a return to war. The government and the people do not want this, and neither does Farc. All parties have spoken of the current ceasefire remaining in place. Rather, the referendum result means that the terms of the peace are to be revisited – in particular, the terms of the amnesty that former Farc fighters are to be given. The people have spoken: they want peace, but they do not want it at any price. The vote seems to reflect a widespread feeling that those who have committed crimes such as murder should not now be given a retrospective pardon.

Farc has recently made moves to show repentance for its crimes, but for many who have suffered at the rebels’ hands these are merely gestures. Farc, like other terrorist movements, has to be held to account for what it has done. In Colombia as elsewhere, there can be no peace without justice, and the victims of violence have a right to be heard.