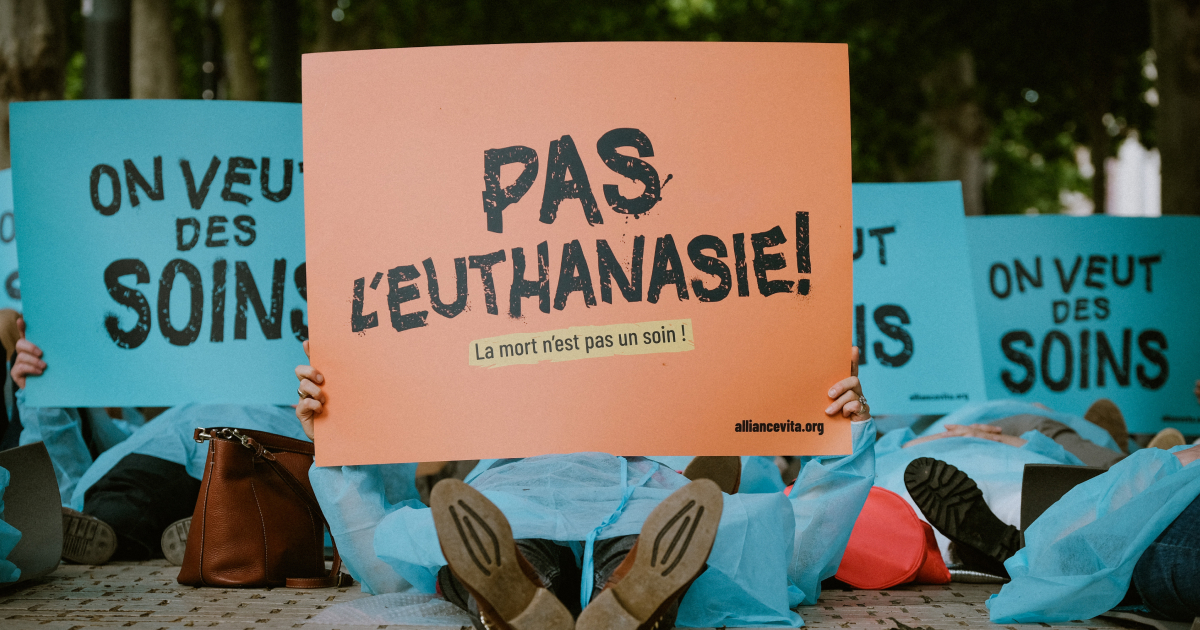

A proposed French law on assisted suicide could force Catholic hospitals, care homes, and nursing homes either to permit euthanasia on their premises or face closure, according to a warning issued by the European Centre for Law and Justice (ECLJ).

The Strasbourg-based legal NGO said the bill, currently before Parliament, would represent an unprecedented intrusion into the freedom of conscience and religion of faith-based institutions, placing them under an obligation to allow euthanasia and assisted suicide even when this directly contradicts their founding principles.

In a detailed briefing written by its director, Gregor Puppinck, the organisation said the draft legislation would expose directors of Catholic institutions to criminal prosecution if they refused to allow the practice within their establishments. Those found guilty of “obstruction” could face up to two years in prison and a fine of €30,000, alongside the possible withdrawal of public funding and administrative sanctions.

“This is a very serious attack on the freedom of Catholic retirement homes and care facilities,” the ECLJ said, arguing that religious congregations caring for the elderly and vulnerable cannot accept euthanasia “for the people entrusted to their care” without betraying their mission.

The bill, formally titled a law on the “right to aid in dying”, has already been adopted by the French National Assembly and is now under scrutiny in the Senate. Under its provisions, all healthcare and medico-social establishments, public and private, would be required to allow euthanasia and assisted suicide to take place on their premises, regardless of their ethical or religious identity. Refusal would constitute a criminal offence.

The ECLJ said no other country in the world that has legalised euthanasia imposes such an obligation on private institutions or couples it with criminal sanctions. While the bill recognises a right of conscientious objection for individual doctors and healthcare staff, it does not extend this protection to institutions themselves.

To highlight the implications, a group of Catholic hospital congregations, supported by legal experts, published an opinion article in Le Figaro at the initiative of the ECLJ. Mr Puppinck described the intervention as a “cry of alarm” and urged readers to alert elected representatives to the consequences of the legislation. The ECLJ has also made senators’ contact details available on its website. Writing separately in La Croix, Mr Puppinck said the French proposal stood out internationally for its “radical and liberty-restricting” character and warned of its potential impact on religious freedom.

The ECLJ has pointed to the experience of other countries where euthanasia has been legalised to illustrate the pressures faced by Catholic institutions. In Belgium, a 2002 law initially allowed religious facilities to avoid the practice, but subsequent legal changes led to growing conflict. In 2020, legislation barred institutions from asking staff to refrain from performing euthanasia, and 15 psychiatric hospitals run by the Brothers of Charity later lost their Catholic status after accepting the practice.

In Canada, assisted suicide was legalised in 2016, and disputes between Catholic institutions and public authorities have intensified. In March 2024, a judge of the Quebec Superior Court ruled that access to euthanasia took precedence over the religious freedom of a Catholic palliative care centre in Montreal, Maison St-Raphaël, rejecting a request for a temporary exemption while the case proceeds. In British Columbia, Irene Thomas Hospice lost 94 per cent of its funding after refusing to allow euthanasia, while St Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver is facing legal action after transferring a patient seeking assisted death to another facility.

By contrast, the ECLJ noted that other jurisdictions have explicitly protected institutional freedom. In the United States, several states safeguard the right of healthcare facilities to refuse assisted suicide. In the Netherlands, where euthanasia was decriminalised in 2002, it was not established as an individual right, and no institution is required to provide it. In New Zealand, the High Court has ruled that hospices and organisations may choose not to offer assisted suicide services and cannot be penalised for refusing to do so.

Public opposition from Catholic voices in France has begun to emerge. On 11 December, Sister Agnès, a doctor and member of the Little Sisters of the Poor, warned on Radio Notre Dame and RCF that the bill threatened the very existence of religious care homes. “Courage is needed,” Mr Puppinck said, noting that many such institutions depend heavily on state funding and would be vulnerable to pressure.

The issue is not simply a dispute over euthanasia policy in France, but a direct, state-sponsored attempt to redefine the moral limits within which Catholic institutions are permitted to exist. It is now a battle over whether religious bodies may continue to act publicly in accordance with their faith, or whether they will be tolerated only insofar as they conform to the ethical priorities of the modern state. With the Catholic Church running more than five thousand hospitals world wide and almost fourteen thousand dispensaries, an erosion between state and church ties could have severe implications for global healthcare.

Catholic institutions are not marginal charities but living expressions of a coherent vision of Catholic life. When the state compels such institutions to facilitate acts they believe to be gravely wrong, it moves from regulating healthcare to acting as a moral authority, effectively asserting that any Catholic vision has no legitimate place in public life.

We have seen before how appeals to neutrality and rights language are used to hollow out Catholic institutions, not by persecution in the classical sense, but by making fidelity impossible. What is unfolding in France fits a familiar trajectory, and it demands a response that is cultural and strategic, not merely reactive.

The immediate catalyst is the proposed French law on the so-called “right to aid in dying”, now moving through Parliament after adoption by the French National Assembly. As legal experts have warned, including the European Centre for Law and Justice, the bill would make it a criminal offence for healthcare and medico-social institutions, public or private, to refuse to allow euthanasia or assisted suicide on their premises. Directors could face prison sentences and heavy fines, while institutions themselves risk the loss of public funding and regulatory sanctions.

This goes far beyond the legalisation of euthanasia as an individual option. Even where such practices are permitted elsewhere, states have generally accepted that religious institutions may decline to participate. The French proposal deliberately rejects that settlement. While it allows individual clinicians to object on grounds of conscience, it denies that institutions themselves can possess a moral identity worthy of legal respect.

For a Catholic institution, this distinction is incoherent. Hospitals, care homes, and hospices founded by religious congregations exist to embody a moral vision in practice. Their refusal to participate in euthanasia is not an incidental preference but arises directly from the Church’s teaching on the dignity of human life. To force them to choose between fidelity and survival is to aim, indirectly but effectively, at their disappearance.

This is not an isolated development but part of a wider Western pattern. Wherever the state adopts an expansive, quasi-moral role, institutions grounded in pre-modern or religious anthropology are recast as obstacles to progress. Indeed, British Catholics might recognise the shape of this conflict. In 2005, equality regulations meant that Catholic adoption agencies in England and Wales were required either to place children with same-sex couples or to sever their formal ties with the Church. One by one, agencies that had served vulnerable children for decades were secularised or closed. The argument then, as now, was that religious bodies could continue only if they compartmentalised their beliefs, treating them as private convictions with no public consequence.

France’s euthanasia bill applies the same logic with even greater severity. It does not merely regulate services; it criminalises institutional dissent. The underlying assumption is that moral resistance grounded in religious tradition is irrational, obstructive, and ultimately illegitimate.

The Church therefore faces a choice. It can continue to argue case by case, pleading for tolerance as an exception. Or it can recover confidence in proposing its own vision of the human person and the common good, not as a private belief system but as a public good capable of shaping culture.

This does not mean withdrawing from society, nor does it mean merely litigating. It means rebuilding Catholic cultural confidence, whether in education, healthcare, law, or public debate. The Enlightenment settlement that once promised neutrality has, in practice, produced a moral orthodoxy of its own. If Catholic institutions are always placed on the defensive within that framework, they will steadily be eroded.

If Catholic culture does not shape the public square, it will be reshaped by it. And if the Church does not act until its institutions are threatened, it will always be acting too late.