Today’s critics have a blind spot when it comes to religion, says David Cowan

No Idols: The Missing Theology of Art

by Thomas Crow, Power Publications, 144pp, £18

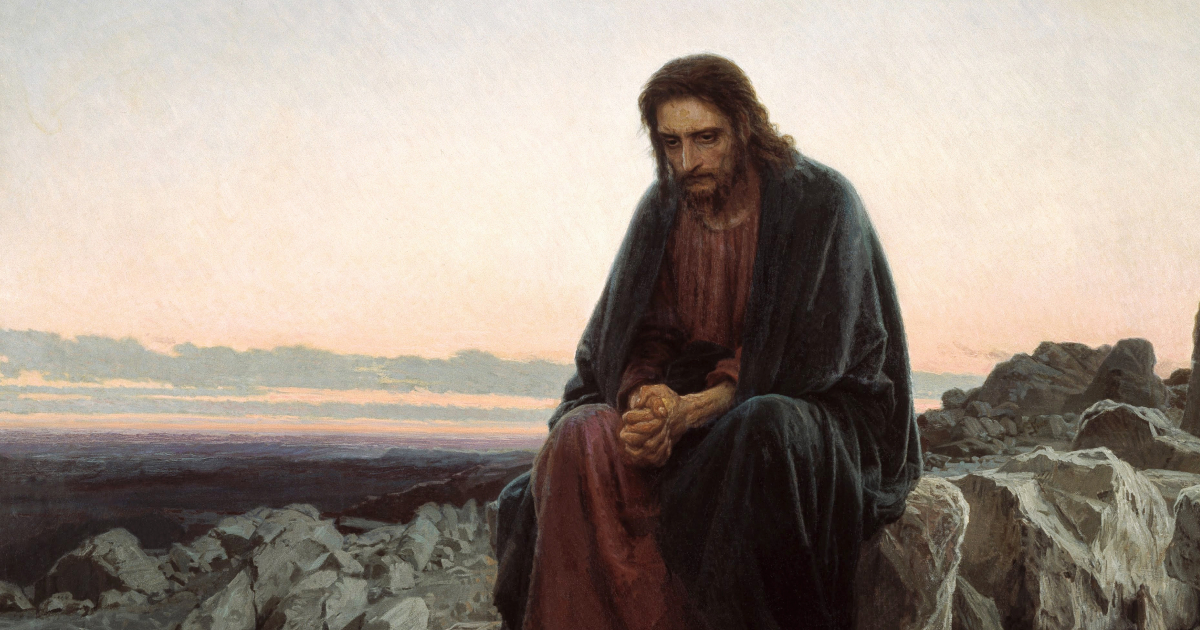

It is increasingly difficult to detect spirituality in art, especially when art is largely seen through recording devices and smartphones or used as a backdrop for selfies.

Using theological language to articulate art is even harder. This surprising volume is an attempt to explain why this is the case, and makes a plea for the restoration of theology in art criticism.

New York University’s Thomas Crow poses the question of whether modern art, specifically art-historical criticism, has stripped religious art of its theological significance. Like Gregorian chant used as mood music, art is separated from its spiritual resonance. The theology is submerged by secular values. Crow writes that Christian devotion, the raison d’être of religious works, has been effectively displaced from the field of art history. Religious doctrine and practice appear as cultural artefacts to be dissected and decoded with clinical detachment. Devoid of its original meaning, nothing is truly at stake for the viewer. The critic doesn’t want us to peer into religious art and see that our very soul is at risk in the encounter. The divine within us all, and thus in all art, is obscured by the interpreter and educator.

These specific art-historical questions are explored through the still-life works of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, Colin McMahon, Mark Rothko, James Turrell and Sister Corita Kent. You may not have heard of all of these artists. Even if you have, you might not like their work.

But Crow uses them to demonstrate that however anaesthetised modern audiences may be, the divine power still seeps through art.

Crow concludes that modern art criticism has created “a gap that cannot be filled, an obscurity that cannot be illuminated, until the reigning interdiction of theology is lifted”. I would add that the same holds for the majority of contemporary cultural criticism. Happily, and Crow highlights this very well, the power of the divine is ever-present.

Despite secular criticism inventing sacred games using crucifixes, the Madonna and biblical stories as source materials for art, there remains a theological itch that the secular is always in need of scratching.