Faith challenges our natural human instinct for justice and revenge

My son warned me how I would feel after having had my phone snatched in a bike-mugging in London: guilty and stupid. Guilty because I had (possibly carelessly) allowed my electronic life to be ripped out of my hands. Stupid because I wished I had kept a more permanent and alert lookout for the thieves who now seem perpetually to prowl our streets.

But the swooping Nazgûl on turbo-charged electric bikes either skilfully grab phones at passing high speed or, more brutally, knock their victims to the floor while doing it, to impede resistance or recovery. If they strike unseen, the act of robbery is instantaneously effective.

My son was right: I felt guilty and stupid. But that wasn’t where the more serious spiritual or ethical complication lay, because I felt furiously angry as well.

Last year, there were 70,000 phone thefts on the streets of London – the vast majority at the hands of muggers like mine, who make a quick and rich living from simply trading in the handsets.

I managed to wipe my device remotely, to protect my data, within a couple of minutes of the theft. I was without my phone, or access to my emails and bank accounts. All I had was fury, frustration and anger.

It was made worse by the little app that allows you to find your phone. It showed me where mine had been taken for about 48 hours. What was really infuriating was that as I tried to persuade the police to help recover it and arrest the thieves, they declined on the grounds that the level of accuracy was not sufficient: the signal might cover several flats and they couldn’t tell which one it was in.

I didn’t share their scruples. When I was an Anglican clergyman in the East End, I could have turned up with a few of my rougher parishioners who would have been far less fastidious than the police about helping me recover my property. But those days are gone, and I was left with a thirst for justice tinged with revenge and warmed by simmering anger.

But there comes a moment in life when the danger to one’s property is outweighed by the danger to one’s soul. The natural desire for revenge was of more consequence than losing my valuable (and uninsured) phone and its contents.

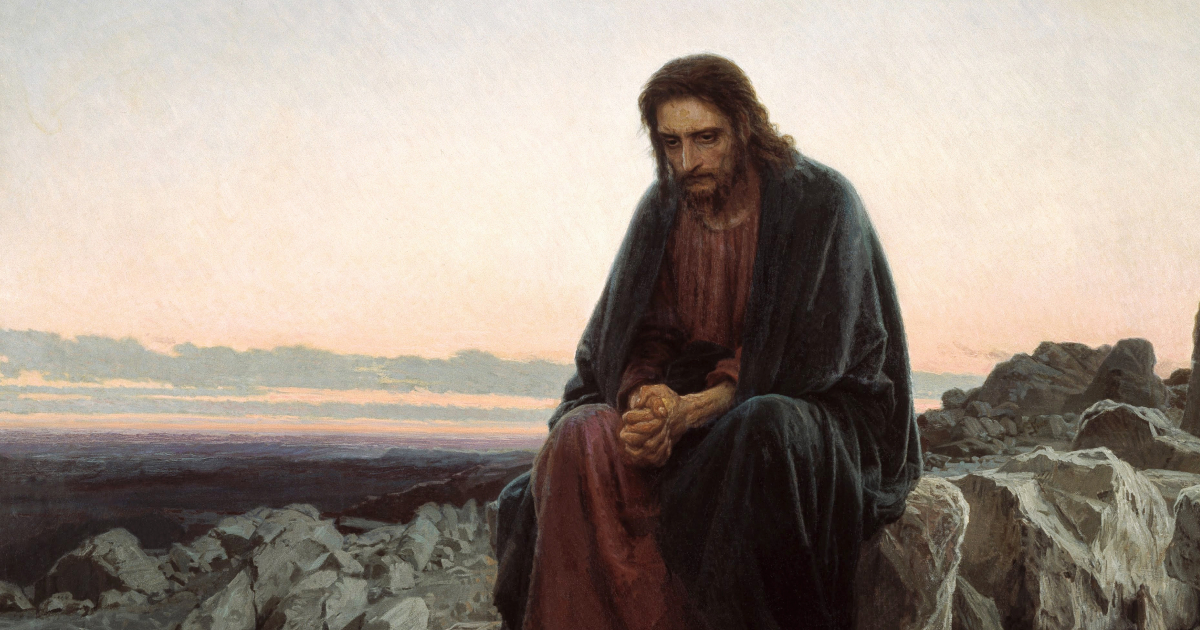

The difficulty with being a believer is that, as GK Chesterton reminds us, “The Christian ideal has not been tried and found wanting; it has been found difficult and left untried.”

And how difficult, how almost impossible it seems. Love your enemy becomes love your robber. Love your mugger. When all I wanted initially was justice for my mugger – and a spot of personal revenge.

At this point, the relativist reading of religion from which our spiritually inept generation suffers is exposed as vacuous. Only Jesus makes this near-impossible demand of His followers; no other religion asks it, although some urge something like it for your peace of mind.

Plato and the Stoics advise against trying to take revenge so that your soul does not get eaten up with bitterness. Even the splendid Confucius suggests a little restraint when it comes to benevolence and enemies: “If you repay injury with kindness, then what do you repay kindness with? Rather, repay injury with uprightness and kindness with kindness.”

Victor Hugo comes to the rescue of any soul at this critical juncture. Les Misérables clothes the teaching of Jesus in the drama of the human story, and suddenly I find I can understand why an enemy has to be loved.

When the Bishop of Digne confronts greed, desperation and violence in Jean Valjean by making a gift of what he had stolen – and adding to the gift with superfluous generosity when he is hauled before the police – he reverses the river of fate, setting the criminal free from evil and self-destruction.

“Do not forget,” he urges, “do not ever forget, that you have promised me to use the money to make yourself an honest man… You no longer belong to what is evil but to what is good. I have bought your soul to save it from black thoughts and the spirit of perdition, and I give it to God.”

I could not see the face of my mugger; I only ever saw the back of his hooded head. I could not judge if he was desperate for money and in trouble, or a violent, grasping embodied force of greed and selfishness.

But through Hugo’s eyes – in the transfiguration of Valjean – the possibility of redemption is acted out in such a vivid and powerful way that the command to love one’s enemy becomes neither a burden too demanding to achieve nor a moral too heavy to carry. It becomes a human story I can grasp, while I observe the mechanics of salvation breaking the grip of revenge, softening the demands of justice and threatening to melt the human heart with a compassion that is neither earned nor deserved.

This article appeared in the April edition of the Catholic Herald. To subscribe to our award-winning, thought-provoking magazine and have independent, high-calibre, counter-cultural and orthodox Catholic journalism delivered to your door anywhere in the world click HERE.

(Photo credit should read MARK RALSTON/AFP via Getty Images)