What seminarians need in a spiritual director

I recently discovered the delights of Malta for the first time, with a certain sense of frustration that I hadn’t thought to go sooner. The architecture and art, especially of the beautiful churches, and the ancient walled cities redolent of the Knights of Malta who defended the faith there until Napoleon expelled them – all these make me want to go back soon.I travelled little in my youth and it is only since becoming a priest that my air miles have shot up. This trip, too, was work, but mixed with a lot of good priestly fraternity and a chance for some sightseeing and a short pilgrimage in the footsteps of St Paul.

I was attending the annual conference of English-speaking seminary spiritual directors from Europe. This year the Maltese hosted us in the seminary complex in Rabat, next to the walled city of Medina.

The focus for this year’s discussions was how to form seminarians for celibate chastity. A spiritual director’s task in the seminary is fundamentally different to that of other staff. He does not express an opinion or vote on a candidate’s suitability for priesthood. He may have strong views on this, and for good reason, because seminarians are encouraged to open their consciences to their spiritual director over their motivations and struggles, in this as in all areas of their life.

But this is an internal forum, precisely to protect the seminarian’s freedom of conscience. It means accompanying the seminarian, listening and reflecting back what the seminarian presents about his motivations, helping him to recognise the movements of his heart and what these mean.

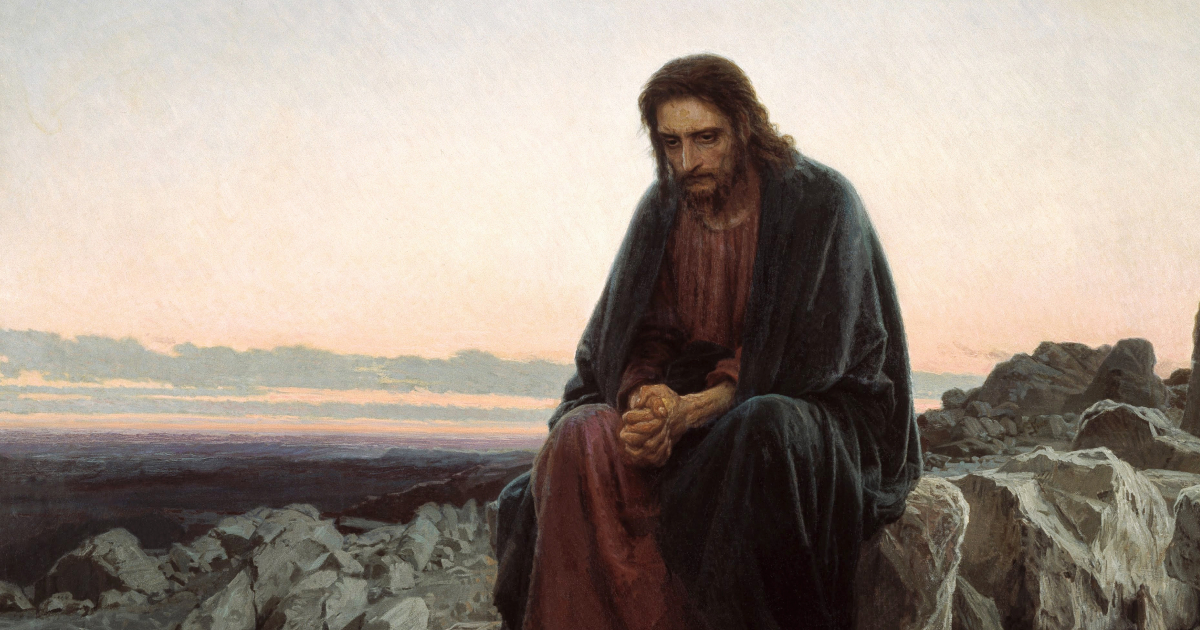

Spiritual direction is not a kind of divination of the seminarian’s inner motives. It is designed to develop in the would-be priest a deeper response to the call which led him to seek admission to the seminary. The question Saul of Tarsus asks when blinded on the road to Damascus is “Who are you, Lord?” This is really the task of the spiritual director, to encourage an ever depending thirst and curiosity about the Lord who calls.

Now, this search for knowledge of the Lord will, of course, invite reflection on oneself and one’s suitability for discipleship, but this is not a therapeutic model where the candidate discusses just himself and his difficulties in self-realisation. “Who are you, Lord?” is different from “How am I doing, Lord?”

Spiritual direction is directed first not towards self-discovery but to the discovery of the Trinity and its self-communication in the Holy Spirit. It is this gift and intimacy which offers the possibility of growing in a human maturity modelled on Jesus Christ and effected through the action of grace on nature. “In your light we see light,” says the psalmist. So growth in self-knowledge and self-acceptance come also, but as the consequence of seeking God and learning to allow oneself to be found and loved by him.

The explicit goal of spiritual direction is to recognise that, as Augustine would put it, my heart is going to be weary until I find the Lord, that there is no authentic “me” to be had by reflecting merely on myself or even by throwing myself wholeheartedly into good works. True fulfilment is found in seeking God, in praying to him and responding to his love. This is the basis for discipleship.

Love for God grows only through prayer and the efficacy and authenticity of my prayer is measured not by my own satisfaction or by the quality of how I experience it, but by growth in an authentic love of neighbour. No one exemplifies this better than St Thérèse, who says: “I have discovered that the more my life is centred in Jesus, the more I am able to love the Sisters.” In a similar way, we can talk endlessly about ways of forming men for celibate chastity, but the real formation is helping a candidate to be “alone with the Alone”.

There are all kinds of pastoral and practical motives for celibacy. None of them in themselves will sustain perfect chastity unless in prayer a would-be priest has located some hint of the joy, satisfaction and communion for which he longs in the embrace of the Blessed Trinity. Like Jesus at the Well of Sychar, the spiritual director’s task is to help a soul conceive and focus desire. “If you but knew the gift of God …”

Pastor Iuventus is a Catholic priest in London