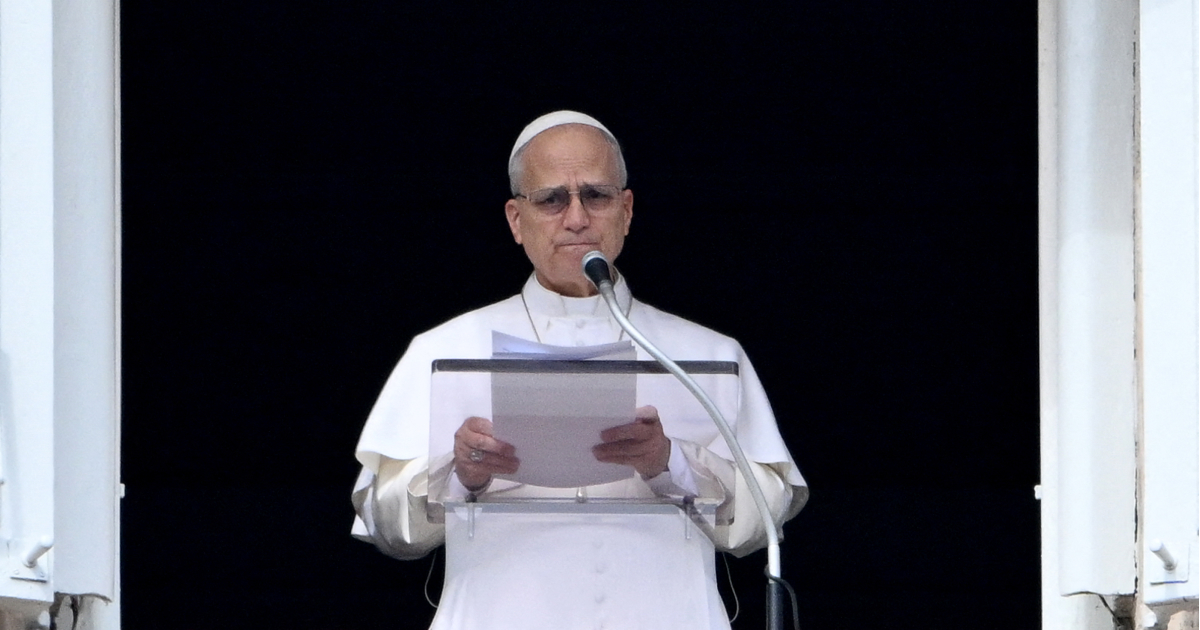

This papacy, much like the one before, is proving to be one of symbols. When Pope Leo XIV stepped out onto the loggia wearing the red mozzetta, he instantly endeared himself to those wanting a return to a stable, Benedict-style papacy. Catholics who felt sidelined by years of turbulence were quietly relieved before he greeted the crowd gathered in St Peter’s Square.

The name Leo also indicated what papacy we might expect. The most recent Leo, Leo XII, who enjoyed a longer-than-expected pontificate at the end of the nineteenth and the very beginning of the twentieth century, was described as having an intellectual, diplomatic, and cautious disposition. He was 67 when he came to the throne, while Leo XIV was 69. Leo XIII came to the Chair of St Peter at the beginning of a period of immense societal change, marked by mass industry, urban expansion, global trade, and labour movements, a period often described as the Second Industrial Revolution. Leo XIV has come to power at the beginning of what might be called a second digital revolution, an age of accelerated technological advancement driven by artificial intelligence.

A mirror copy of any previous papacy is implausible, and perhaps even unwelcome, but the papal name was itself a symbol of a return to a period associated with a stable pontificate. Leo XIV is yet to write his own Rerum Novarum, though we might expect to see it within the coming years, but his choice in papal name is deeply indicative of the kind of papacy he would like to lead.

But perhaps the most striking symbolic moment of the papacy so far came on his first foreign Apostolic journey. The Holy Father arrived in Turkey, the cradle of Christianity which under Islamic rule has seen its Christian population almost disappear, to commemorate the 1,700th anniversary of the Council of Nicaea. On the third day of his visit, the Pope travelled to the Blue Mosque, an iconic imperial mosque in the heart of Istanbul and an emblem of the country’s Islamic identity.

The history of popes visiting mosques belongs entirely to this century. Pope St John Paul II was the first to do so in 2001, when he visited the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, Syria, during his Jubilee pilgrimage to Greece, Syria, and Malta. Even during his visit to the Christian nation of Greece, opposition had been fierce, with many Greek Orthodox leaders objecting to the journey. The controversy continued upon his arrival in Syria, where the Pope’s decision to visit the mosque was met with particular resistance. A senior cleric in neighbouring Lebanon, Sheikh al-Hout, attempted to dictate terms, telling the press, “In a Muslim state, crucifixes should not be displayed in public, all the more so inside an Islamic holy place. The Pope must respect these conditions like anyone else.” Fortunately the local prelate, Archbishop Isidore Battikha, had no such scruples, informing the press that “the cross will be prominent on the Pope's vestments when he enters the mosque”. As it turned out, the trip also included the pontiff pausing in prayer inside the mosque.

Like Leo, Popes Benedict XVI and Francis also visited the Blue Mosque. Benedict’s 2006 visit was overshadowed by the fallout from the Regensburg lecture, during which the Pope had quoted the Byzantine emperor and Christian monk Manuel II Palaiologos criticising Islam. Entering the mosque, Benedict paused for around two minutes in silence. The Turkish daily Milliyet reported on the moment with the headline “Like a Muslim”. Vatican spokesman Fr Federico Lombardi commented later that “the Pope paused for meditation and will certainly have turned his thoughts towards God.”

Pope Francis appeared to go further on his own 2014 visit. Standing alongside Istanbul’s then-Grand Mufti Rahmi Yaran, head bowed, hands clasped, Francis prayed quietly for several minutes. The Grand Mufti responded afterwards by saying, “May God accept it.”

With the current direction of traffic for outward expressions of interfaith congeniality, it might have reasonably expected that Pope Leo would follow suit. Indeed, the Vatican’s own record of the event initially put Leo as pausing for prayer.

On entering the Blue Mosque one of its imam’s, Asgin Tunca, invited the Pope to pray, saying “It’s not my house, not your house, (it’s the) house of Allah.” However, Pope Leo responded to the invitation by politely declining. The Vatican then corrected its earlier assertion that the Pope had prayed by saying he had visited the mosque "in a spirit of reflection and attentive listening, with deep respect for the place and for the faith of those who gather there in prayer."

Like wearing the mozzetta or choosing the papal name Leo, the decision not to pray in the mosque was itself symbolic. It was not, as those who frame Christianity’s purpose as opposition to Islam might insist, a rejection of Muslim belief. It is, however, an acknowledgement that a journey to increased cooperation with faiths outside Christianity is not the role of the Roman Pontiff. Faithful Catholics, with some justification, have been scandalised by Church leaders allowing inter-religious dialogue to spill into shared prayer and it appears that Leo has acknowledged these anxieties, choosing to put the obligations of his office he leads ahead of optics to please a secular press.

The clues to this change in tack are outlined in the book Leo XIV: Citizen of the World, Missionary of the 21st Century by veteran Vatican correspondent Elise Ann Allen. In the book, which is based on lengthy interviews, he tells Allen candidly: “I don’t see my primary role as trying to be the solver of the world’s problems”. In other words, the Pope is interested in what pertains to the Church, in her mission to bring people to a knowledge of Jesus.

Whilst inter-religious dialogue may be in vogue, because secular society is certain it will lead to greater harmony, secular dictates rarely make good Christianity. Two hundred years ago secular society argued that people could be enslaved. Fifty years ago it moved to say the unborn did not merit full human dignity. Now it debates whether those who are physically or mentally ill might be better off dead. Whether one agrees on every point or not, Christianity carries a longer and more coherent moral framework than any outside it.

Equally, respect for another religion is not capitulation. By all accounts, no offence was taken by actual Muslims. A hybrid of Islam and Christianity would be an affront to the foundations of both.

Allen's book also gives insight into what may well be a central priority for this papacy: mending the scandal of disunity amongst Christians. In the book, he makes it clear that he hopes to “build bridges” with the Patriarch of Moscow and the Patriarch of Constantinople, because “we all believe in Jesus Christ, the Son of God and our Saviour.” He had no reservations about praying at the Armenian Apostolic Cathedral in Istanbul, where he joined Bartholomew I and over 400 members of the Holy Synod of the Ecumenical Patriarchate for the Divine Liturgy on the Feast of Saint Andrew.

Whilst Pope Leo’s decision not to pray in a place not intended for Christian worship may unsettle secular impulses that seek to blur the lines between religions, it is a clear indication that his priorities are not of this world. He is concerned with the Church, both in communion and separated. His trip to the ancient Christian lands of Turkey made this clear.