On Monday, 12 January, the liturgical Christmas season gives way to Ordinary Time, and with this, though there are some diehards who will keep their crib up for another few weeks, Christmas is for most of us well and truly over. The brief interlude of magic, the crib, carols, decorations, and celebrations, gives way to the prosaic, the banal, and frankly the boring period of Ordinary Time. Now it is, as they say in an Ulster expression I love, “back to porridge”.

And in the Northern Hemisphere, at least, there could be nothing less magical than the month of January. Research, perhaps of a slightly tongue in cheek nature, released in 2005, even concluded that the combination of bad weather, debt, failed resolutions, and post Christmas fatigue all combine to make the third Monday of January the most depressing day of the entire year, “Blue Monday”. While the research behind Blue Monday was promoted by the UK tour agency Sky Travel to encourage people to book holidays as an antidote to January gloom, there is nonetheless, many feel, something to it. How could one not feel a little blue about dark winter mornings, alarm clocks, rushed breakfasts, cold wet weather, traffic, and the works?

But Mother Church does nothing to soften the blow, nothing to ease the transition from festivity to banality. She simply says, “Back to work”. That is not to say that we will not do everything possible to put off the evil hour: burrowing into some fantasy on our phones, ferreting out a precious hit of dopamine via some utterly reckless online purchase, or simply booking that sun holiday, just as Sky Travel suggests.

Alternatively, we could take the plunge and enter wholeheartedly into Ordinary Time once more. Indeed, we need to discover that there is something actually quite extraordinary about Ordinary Time. We must overcome the prejudice against ordinariness that is baked even into our language. The very word ordinary in English carries a tinge of contempt. “How ordinary!” was once a common response to a display of vulgar language or behaviour. In other languages, such as French or Spanish, the corresponding word is even more overtly synonymous with what is coarse, low class, or vulgar.

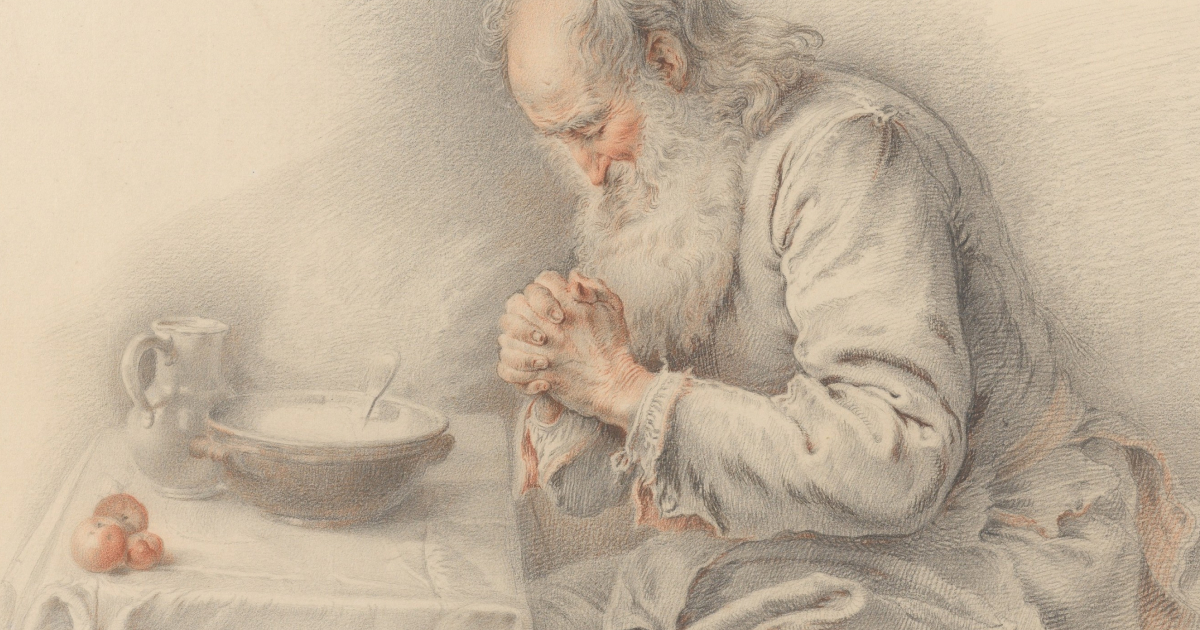

While the ordinary is, by definition, not extraordinary, and the term readily conjures up what is routine, predictable, and therefore a little boring, nevertheless beneath the surface the ordinary has a magic of its own. This is reflected in the liturgical colour of the season, green, signifying life and growth. The heavy lifting happens in Ordinary Time and in ordinary life. The short liturgical escape into the season of Christmas is magical, but God is waiting for us in the most ordinary things: the nine to five, the traffic, even the alarm clock.

Many saints have pointed us towards the extraordinary hidden in the ordinary: St Benedict of Nursia, for whom “nothing is small in the service of God”; St Francis de Sales, who wrote, “Do not wish to be anything but a simple, ordinary person, and the Lord will do great things through your ordinary life”; the “little way” of St Thérèse of Lisieux; and St Josemaría Escrivá, for whom “there is something holy, something divine, hidden in the most ordinary situations, and it is up to each one of you to discover it. Either we learn to find our Lord in ordinary, everyday life, or else we shall never find Him”.

The Incarnation of Christ itself, which we have been celebrating and reflecting upon for the past few weeks, reveals much about the hidden value of the ordinary. The very fact that the Gospel writers have nothing to tell us about the life of Jesus between his extraordinary birth and the inauguration of his public ministry, with the sole exception of the episode of his going missing in Jerusalem, speaks volumes. There was, quite simply, nothing outwardly extraordinary about Christ’s young life. He lived the same life as any Nazarene of his age: growing up within a family, receiving a basic education, learning the trade of his foster father, making friends with local boys, entering into the social life of the area, being instructed in the faith of his parents, and growing to love dearly his own people.

Undoubtedly, Jesus himself had his own equivalent of our Monday mornings, moments when, humanly speaking, the going was uphill. And yet Jesus clearly cherishes the very ordinariness which he, the second person of the Blessed Trinity, lived out with us for three decades. How lovingly he recalls, in his parables, details of the ordinary life in which he was immersed: children playing games in the marketplace; men waiting to be hired; neighbours borrowing bread at night; crops being sown and tended; sheep being carried on shoulders; women baking bread, and so on. Here there are no miracles, or at least no overt miracles. There is only the slow growth in virtue, the gradual increase in our capacity to love, worked out through games, labour, relationships, and small incidents: the porridge of everyday life.