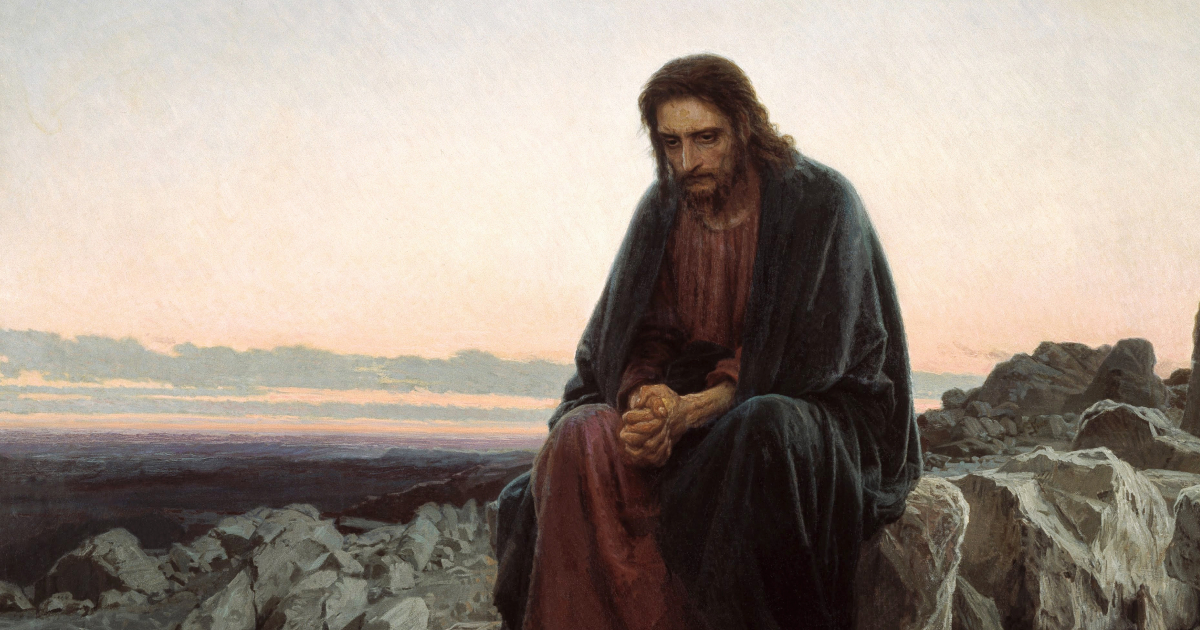

The premise of Lent is that it is like Christ’s sojourn alone when he “was there in the wilderness forty days, tempted by Satan; and was with the wild beasts; and the angels ministered to Him.” Angels and wild beasts … what wonders that conjures up. But no food. His cousin, John the Baptist, dressed in camel skin, only emerged from the wilderness to begin a career of preaching and baptising: he too encountered those wild beasts. John subsisted on locusts and wild honey, a sticky and inadequate diet. Christ’s 40 days, of course, echo the 40 years that the people of Israel spent in the desert, with a diet enlivened by quails and manna.

The contemporary Catholic Lent is a more forgiving affair, at least in duration. Between Ash Wednesday and Easter Saturday there are more than 40 days, usually 44. That is because Sundays do not count, for every Sunday is a feast of the Resurrection. The 40 days are therefore punctuated by days off fasting, which gives the whole thing a less forbidding aspect. When you add to that Lady Day, March 25, the feast of the Annunciation, and St Patrick’s Day, on which fasting would be all wrong, the vista looks less bleak. I have a positive genius for taking the edge off abstinence. Once, when I came back from Medjugorje, where people are encouraged to subsist on bread and water on Wednesdays and Fridays, I tried it. I cannot tell you how quickly bread and water changed into tea and toast … basically the same thing, but very much less of a penance.

Fasting can be eased if it is a social thing, if everyone else is having short rations too. But now that fasting and abstinence in secular society are channelled into the abominations that are Dry January or Veganuary, it is less likely that others around you will at least be giving up chocolate. On the other hand, this year Ash Wednesday coincides with the start of Ramadan (cue for Ramadan lights in London’s West End), so fasting will be very much on the social radar. It will be interesting to see which looms larger: the Christian Lent or the Muslim holy month. Certainly, the example of Muslims not even drinking water during the day should give the rest of us pause.

The community we should really be looking towards during Lent, however, is the Orthodox. They still have a medieval – and I mean that as a compliment – approach to the season; they go the whole hog, except, of course, minus the hog, meat being off the menu. The Orthodox do what the whole Church once did; they abstain from meat and dairy for the duration of Lent. Indeed, they are stricter than that. Olive oil is avoided by some traditionalists on the basis that it was formerly stored in sheepskins and so had the taint of meat. Only some fish is allowable, some of the time, but all fish is permitted on Lady Day and Palm Sunday. In fact, if you add up all the fasting days in the Orthodox calendar, it comes to about 200 for strict Greek Orthodox and 210 for Copts.

So I think we should return to basics, channel the Eastern Churches and try at least to give up meat for Lent (you are bearing in mind that Sundays do not count?). If possible, it is worth trying to eschew dairy too. The thing is, these are simple to understand and concrete, whereas if you try to do something “positive”, it all gets a bit inchoate. Obviously, we should be giving alms – the Cafod Friday Fast Day promotes that – during Lent and saying our prayers. But we can do both. It is not either/or.

The one thing to be said about the prevalence of veganism in contemporary culture is that it is far easier than it was to fast and abstain. Oat milk is not great in tea but it is quite nice in coffee. Once, giving up dairy would have meant black tea. If you cannot have butter, a good olive oil is very good with bread. You can get coconut yoghurt rather than the milk sort, which is actually pleasant. We can all do as the Orthodox do and eat lots of beans during Lent. Cooked with onions and doused in olive oil, they are really good, though plainly flatulence is very Lenten. There are many good things in the part of the Greek diet called nistisimo, or fasting food. Apparently, in every Greek home during Lent there is halva, the addictive sesame-based sweetmeat for when you need a sugar rush. The problem, I find, with going semi-vegan is that people will think you actually are vegan – the embarrassment of ordering oat milk in a café – but that can be part of the penance.

Let us not forget fish, the Lenten staple. A nice lobster salad can take the edge off even the most rigorous Lent.

Need I say that in an old-school Lent, sex would have been off limits as well as meat. Funnily enough, that particular aspect of the tradition has not returned to fashion.