Today, King Charles and Queen Camilla will begin their state visit to the Holy See. “Fantastic,” you might say, and there has been the same upbeat reaction from the papers, broadcasters, and social media. Much of the excitable coverage focuses on this particular claim, put out last week in a Buckingham Palace press briefing: “King to be first British monarch to pray with Pope in at least 500 years.”

This all sounds very impressive. After all, relations between Rome and Canterbury, though cordial in recent decades, have been fraught for centuries, and Pope Leo XIV’s own namesake, Pope Leo XIII, declared in Apostolicae Curae that “ordinations carried out according to the Anglican rite have been, and are, absolutely null and utterly void.” Here, then, it seems, is confirmation that the monarch and the Pope have reset relations to where they were before 1535.

Except, they haven’t. The Buckingham Palace briefing, with the best of intentions, suggests that English monarchs up until 500 years ago made a habit of praying with Pontiffs. That’s not the case – still less is it the case that they held joint ecumenical services. However, Dr James Willoughby, an Oxford medievalist, has pointed out that it was quite a lot further back when an English king met a pope. “Henry I prayed with Pope Calixtus II on the Norman-French frontier in 1119. And Edward I was technically king (his father was dead, but he had yet to be crowned) when he visited Rome in 1272, praying with Pope Gregory X.” The century before also saw King Cnut meet with Pope John XIX in Rome during his 1027 pilgrimage.

However, in the earlier, pre-Conquest period, English kings did something else: they went to Rome on pilgrimage, as the place where St Peter and St Paul died. Dr Willoughby notes: “Alfred was the most famous pilgrim to Rome, first in 853 as a four-year-old, when he was anointed by Pope Leo IV. That is recounted by Asser in his Life of Alfred. The West Saxons were good travellers to Rome. Caedwalla, King of Wessex, was baptised there in 689, just before his death. I think he had sepsis from a battle wound. And his successor, Ine of Wessex, retired from public life in 726, went to Rome and built himself a house and died there in 728. He founded the schola saxonum, a pilgrim hospital and chapel dedicated to Santa Maria, and Santa Maria de Sassia became the focus for Anglo-Saxon visitors to Rome. It is now Santo Spirito on the Borgo Santo Spirito, round the back of the Via della Conciliazione. It is Bede who mentions Ine’s abdication to go to Rome.”

No doubt when these royal visitors went to Rome, they had a royal welcome from the Pope of the day, but it’s not quite right to say that there was some sort of tradition of popes and kings praying together. Certainly, there wasn’t anything of the kind from the Norman Conquest onwards. Henry VIII never met a pope, though he did try hard to have Cardinal Wolsey elected as one.

All of this isn’t to say that it’s not a welcome event that the King and the Pope are praying together in an ecumenical service. And it’s worth noting that the Queen knows quite a lot about the faith, since Andrew Parker Bowles, her first husband, is a Catholic, and their marriage was celebrated by a Catholic priest and their children raised as Catholics.

But the way this historic occasion has been presented says something about our ignorance of English relations with the Papacy. The King isn’t reviving an ancient tradition; perhaps he’s establishing a new one.

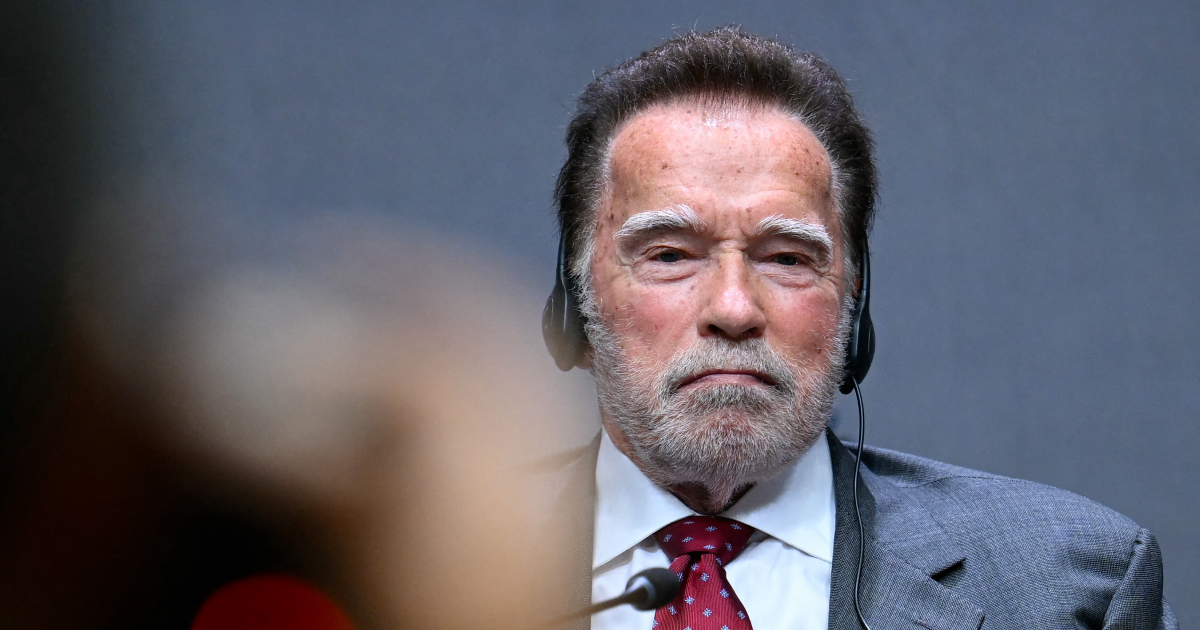

(Photo by ARTHUR EDWARDS/POOL/AFP via Getty Images)

.jpg)