When Our Lady of Guadalupe appeared to the peasant Juan Diego in 1531, Mesoamerica stood at a crossroads. The Aztec Empire had fallen, yet the religious imagination it shaped remained formidable. Centuries of human sacrifice soaked the land and the collective memory. Atop their temples, Aztec priests tore the still-beating hearts from countless victims, lifting them to feed the sun, while the audience below engaged in self-harm as further offerings to satiate their insatiable gods.

The Spanish arrived bearing the Gospel, but also smallpox and the weight of cultural conquest, making the prospect of peaceful conversion both fraught and deeply uncertain. Into this moment of turmoil, Our Lady intervened and sparked one of the greatest and most enduring mass conversions in history.

We are nearly 500 years since her apparition and though we are very different in time and technology, we are strikingly similar in affliction. The Aztecs worshipped false gods who demanded the ultimate human offering; we, too, find ourselves tethered to our false gods that consume us and exact a profound and often violent toll on our humanity.

What are our false gods? Some are explicit, reflected in the rise of the occult. Over the past few decades, Americans identifying as witches, Wiccans or pagans have surged from about 8,000 in 1990 to an estimated 1–1.5 million by the late 2010s. Younger generations increasingly consult astrology, tarot and other New Age practices. What was once a fringe curiosity has metastasised into a sizable subculture.

But of all the false gods that tempt the human soul, none is more common than the god of the self. While pride is a root factor in every sin, there is a starker form of self-deification capturing modern man. I call it the Empowerment Delusion and it stems from a fundamental incoherence: on one hand, individuals believe they possess absolute power to redefine and render meaningless core aspects of what it means to be human — sex, marriage, bodily reality — according to their will. On the other hand, they are told the locus of control over their lives is almost entirely external: the wrong pronouns can eradicate their existence and success or failure in life is predetermined by systemic and structural social forces over which they have no control. In short, the self-god of today is both omnipotent and perpetually victimised. He is all-powerful to change what is fixed and utterly powerless to change what is fixable.

A society of self-made gods is inevitably one of roiling conflict: man against woman, woman against man; adults against the child in the womb; adult children against their parents, as evidenced in the rising rate of kids going no contact with the older generation. The disintegration even turns the individual against himself, as in the self-rejection of transgenderism. Underlying each antagonism is the fundamental one: man against God.

When the self is declared sovereign, that false identity must be protected at all costs. This means cutting out anything that exposes our interdependence or burdens our autonomy, be it the child, the elderly, the family member or the bodily member. Like the Aztec gods, the self, reconceived as a god, is insatiable.

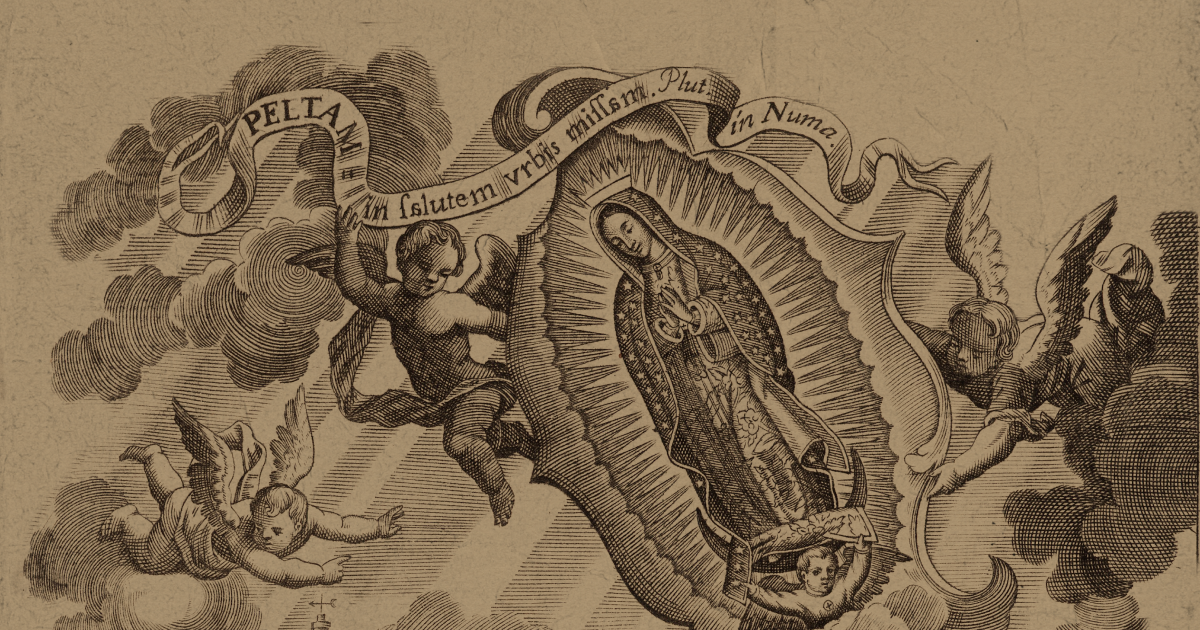

What did Our Lady do in 1531 to turn a civilisation back towards her Son? She powerfully exposed the false gods of the age while expressing profound maternal care. Every detail of the miraculous image on Juan Diego’s tilma speaks a theological language that the Indigenous world would have recognised instantly. The Aztecs worshipped the sun and the moon. But on the tilma Our Lady stands before the sun and upon the crescent moon, in serene dominion over the forces that they had worshipped. Yet her eyes are lowered, her hands folded, her head bowed in a posture of reverence: she is not the goddess, but the God-bearer.

In the late twentieth century, scientists examined the tilma using modern technology. They found within the Virgin’s eyes reflections of tiny human figures, no larger than 1/50th of the pupil itself. These images, invisible to the naked eye, appear with the precise distortion and curvature one would expect from a living eye. Researchers believe they depict Juan Diego, the bishop, his uncle and a family present at the moment the tilma was unfurled. How fitting that God hid certain miracles to be discovered centuries later for an age haunted by its own false gods.

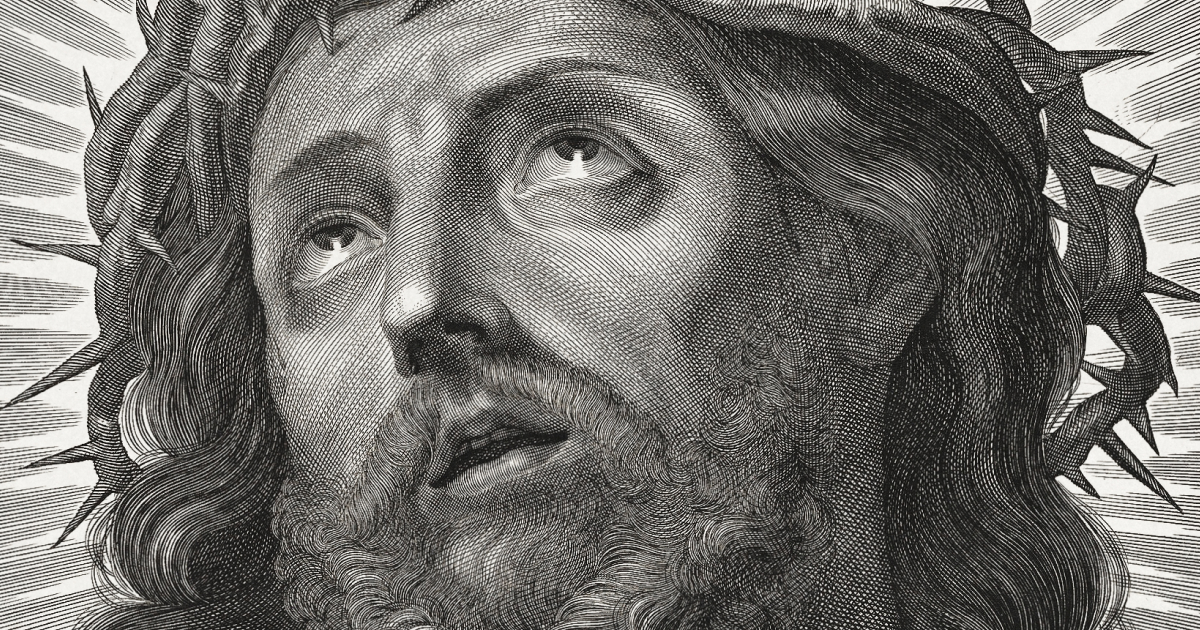

All true conversion is, in some sense, the righting of what has been turned upside down. The Aztecs were correct to see the heart as the greatest gift a human could offer, but they believed human blood sustained the gods, powering the sun’s journey and renewing the earth’s fertility. It was a cosmic reciprocity: our body and blood feed the gods so that the gods may feed the world.

This is an inverted echo of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. In the Eucharist, it is not we who nourish God, but God who nourishes us with his own body and blood. We do give God our hearts, not in violence but in a death to self so that his divine life might grow in us.

“I am the ever-Virgin Mary, Mother of the true God who gives life and maintains its existence.” With those words, she unmasked the falsity and the fear the old gods had long instilled. She overturned a cosmos with the disarming force of a mother’s love. And to a wounded people then, as to us now, she speaks the same assurance: “Am I not here who am your Mother? Are you not under my protection?” In the decade following, ten million souls gave their hearts to Jesus Christ, lifting them up to the one true God and true Victim by whose body and blood we are drawn into the life that sustains all creation. May she aid in upending our false gods now, and lead humanity back to her Son.

Noelle Mering is a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. She is the author of Awake, Not Woke, Theology of Home, and an upcoming book on the No Contact movement. She is a wife and mother of six.