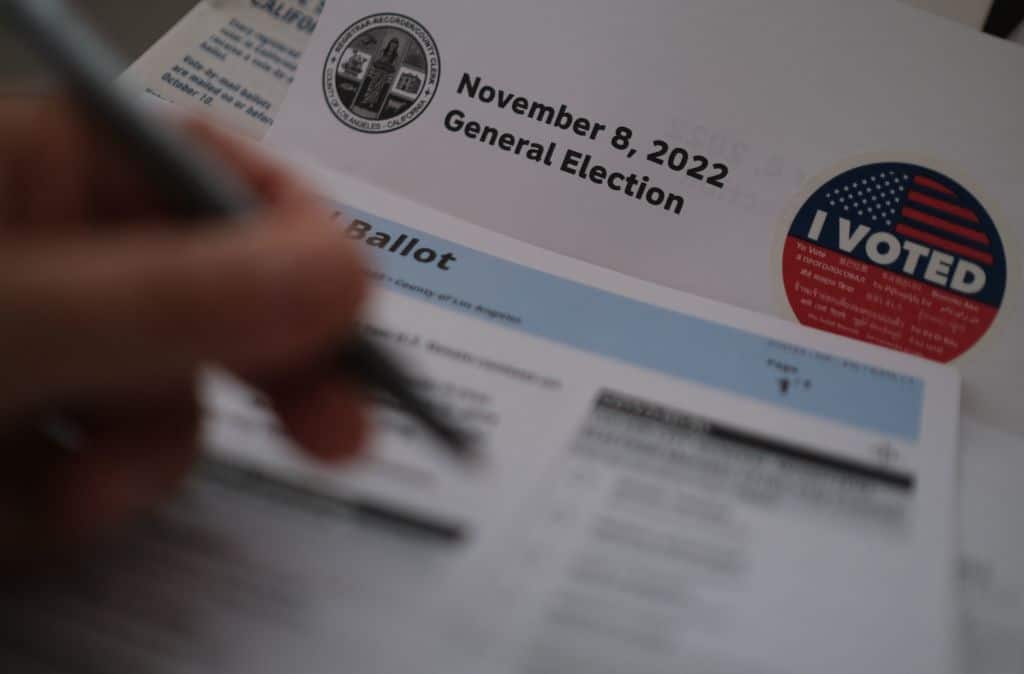

The just-completed midterm elections in the United States are a proxy for the deep ambivalence of American voters about what issues matter most and who is best able to address them.

In the United States, election day for federal legislators and the President is fixed by statute as the “Tuesday next after the first Monday in November”. For convenience, all the States have also established this day for the election of State officials and the choice of referenda (although many states have additional elections for issues and officials peculiar to their constitutions and laws).

While State elections are held every year, elections for federal offices are held in years ending in even numbers. These are the years that we elect (or re-elect) the President (in the years divisible by 4), and (every year divisible by 2) all 435 members of the U.S. House of Representatives and one-third of the 100 U.S. Senators. Elections in the even numbered years that are not Presidential election years are called “midterm” elections, as in the middle of the term of the last-elected President.

Going into the 8<sup>th</sup> November election, the House of Representatives was controlled by the Democrat Party, which held a majority of 221 seats to 212 for the Republicans, with two vacancies. The Senate was equally represented by both parties, each holding 50 seats. This effectively gives control of the Senate to the Democrat Party, because the Vice President, Democrat Kamala Harris, is the tie-breaking vote.

Midterm elections serve not only to choose representatives but also as an unofficial vote of the nation’s relative satisfaction with the occupant of the White House and his party. Midterm elections also reflect the nation’s collective judgment about what issues are more or less important at the time.

Very broadly speaking, President Biden tried to make this election about abortion. Repeatedly, and up to election day, he and his surrogates assured the American public that if the Democrats keep control of the House and enlarge their majority in the Senate, his first action in the new Congress will be to “codify <em>Roe v. Wade</em>”. This would purport to prevent States from making any laws or regulations related to abortion, allowing abortion for any or no reason, at any time and without restriction.

Republicans, on the other hand, campaigned against the Democrats on the issue of the very fragile state of the economy, the worst inflation in more than 40 years, and a dramatic rise in violent crimes. They surmised that Americans are more interested in financial security and personal safety than the supposed right to abortion on demand.

The November 8 midterm election has illustrated that, broadly speaking, Americans seem highly ambivalent about which of these issues they find most compelling.

While final tallies for races in some States are days or weeks away, initial counts show that the Republican party is likely to win a narrow majority in the House of Representatives, while the Democrat Party will probably take a razor thin majority in the Senate. This is in stark contrast to the consensus of pre-election polling, which predicted a significant Republican majority in the House and a narrow Republican majority in the Senate. These probable results are both surprising and difficult to explain, but the difficulty itself illustrates the messy nature of the representative federal democracy of the United States.

Post-election analysis will take some time, especially as some results will not be known for days or even weeks. One State, Georgia, may need a second “run-off” election for its Senate seat, because neither major candidate appears to have garnered the requisite 50 per cent of the votes for an outright victory. And close races in other States will require recounts. What we know now, however, the morning after the polls closed, is that there is no consensus in the United States about what issues are the most compelling or which of the two political parties is the best to address them.

The just-completed midterm elections in the United States are a proxy for the deep ambivalence of American voters about what issues matter most and who is best able to address them.

In the United States, election day for federal legislators and the President is fixed by statute as the “Tuesday next after the first Monday in November”. For convenience, all the States have also established this day for the election of State officials and the choice of referenda (although many states have additional elections for issues and officials peculiar to their constitutions and laws).

While State elections are held every year, elections for federal offices are held in years ending in even numbers. These are the years that we elect (or re-elect) the President (in the years divisible by 4), and (every year divisible by 2) all 435 members of the U.S. House of Representatives and one-third of the 100 U.S. Senators. Elections in the even numbered years that are not Presidential election years are called “midterm” elections, as in the middle of the term of the last-elected President.

Going into the 8<sup>th</sup> November election, the House of Representatives was controlled by the Democrat Party, which held a majority of 221 seats to 212 for the Republicans, with two vacancies. The Senate was equally represented by both parties, each holding 50 seats. This effectively gives control of the Senate to the Democrat Party, because the Vice President, Democrat Kamala Harris, is the tie-breaking vote.

Midterm elections serve not only to choose representatives but also as an unofficial vote of the nation’s relative satisfaction with the occupant of the White House and his party. Midterm elections also reflect the nation’s collective judgment about what issues are more or less important at the time.

Very broadly speaking, President Biden tried to make this election about abortion. Repeatedly, and up to election day, he and his surrogates assured the American public that if the Democrats keep control of the House and enlarge their majority in the Senate, his first action in the new Congress will be to “codify <em>Roe v. Wade</em>”. This would purport to prevent States from making any laws or regulations related to abortion, allowing abortion for any or no reason, at any time and without restriction.

Republicans, on the other hand, campaigned against the Democrats on the issue of the very fragile state of the economy, the worst inflation in more than 40 years, and a dramatic rise in violent crimes. They surmised that Americans are more interested in financial security and personal safety than the supposed right to abortion on demand.

The November 8 midterm election has illustrated that, broadly speaking, Americans seem highly ambivalent about which of these issues they find most compelling.

While final tallies for races in some States are days or weeks away, initial counts show that the Republican party is likely to win a narrow majority in the House of Representatives, while the Democrat Party will probably take a razor thin majority in the Senate. This is in stark contrast to the consensus of pre-election polling, which predicted a significant Republican majority in the House and a narrow Republican majority in the Senate. These probable results are both surprising and difficult to explain, but the difficulty itself illustrates the messy nature of the representative federal democracy of the United States.

Post-election analysis will take some time, especially as some results will not be known for days or even weeks. One State, Georgia, may need a second “run-off” election for its Senate seat, because neither major candidate appears to have garnered the requisite 50 per cent of the votes for an outright victory. And close races in other States will require recounts. What we know now, however, the morning after the polls closed, is that there is no consensus in the United States about what issues are the most compelling or which of the two political parties is the best to address them.