***

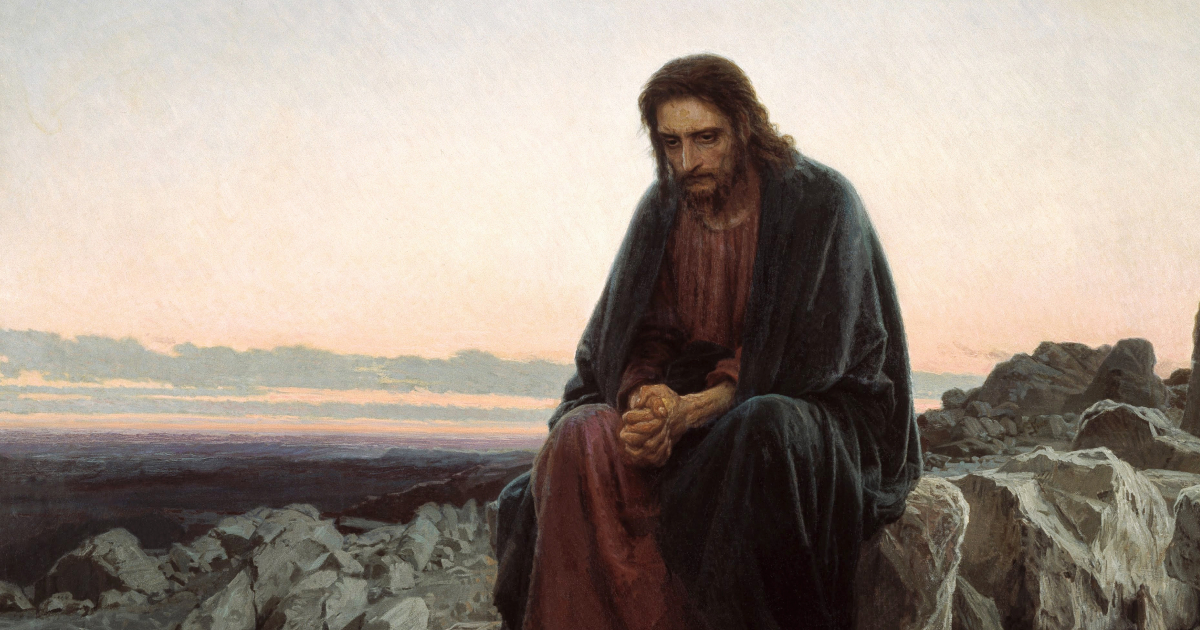

We shall see: there is money, the atom bomb, the cynicism of those who have nothing sacred. How often do we catch ourselves fearing that in the end world history only distinguishes between the stupid and the strong … There is a feeling that the dark powers are increasing, that the good is powerless – a similar feeling to what people once had when the sun was fighting its death throes in autumn and winter. Will it get through it? Will the meaning and power of the good prevail in the world? In the stable of Bethlehem there is placed the sign which joyfully answers us: yes, because this child – God’s only begotten Son – is set up as a sign and a guarantee for this. He is the sign that in the end God keeps the last word in world history, He, who is the truth and the love. That’s the true meaning of Christmas. It is the birthday of the undefeated Light, the winter solstice of world history, which gives us the certainty amid the rise and decline of this story that here, too, the light will not die, but has already achieved the final victory. Christmas drives out of us the second, greater fear that physics cannot dispel. This is the fear of humanity and before man himself. It is a divine certainty that the light has already conquered in the hidden depths of history, and that all the great progress of evil in the world in the end can do nothing more about it. The winter solstice of history has irrevocably taken place in the birth of the Child from Bethlehem. Something, of course, will be noticed on this birthday of the Light, on this entry of the good into the world, and might once again fill us with more anxious uncertainty: that is, whether the great thing about which we are talking actually happened in the stable of Bethlehem. The sun is great, glorious and powerful; nobody can overlook its annual triumphant march. Did not its creator have to be more powerful or even more recognisable when he arrived? Should not this real sunrise of history flood the face of the earth with unnamable splendour? Instead how poor is it all as we hear it presented in the Gospel. Or perhaps this poverty, the inner worldly insignificance, should be the sign of the Creator, with which he marks His presence? This seems to be an inconceivable idea for now. And yet, he who pursues the mystery of the governance of God, especially as it is known in the writings of the Old and New Covenant, sees more and more clearly that there is obviously a double sign of God. There is first the sign of creation, which, through its greatness and glory, lets us suspect that there is one still greater and more glorious. But next to this sign, the other sign, the sign of inner-worldly poverty, emerges more and more strongly with God as the very other to let us know in this way that he cannot be measured by the standards of this world, that he is beyond all such dimensions. It is impossible to better understand this peculiar contrast between the two signs to which God testifies, and the nature of the second sign, the sign of lowliness, than by considering the contrast between the messianic sermon of the baptist John and the messianic reality of Jesus himself. John had described the one who was to come in an Old Testament style as he who would place the axe to the roots of humanity, as a judge full of holy wrath and divine power. How different he looked when he came! He is the Messiah who does not cry out and make a noise in the streets, who does not break the bruised reed and does not extinguish the smouldering wick (Isaiah 42:2f). John had known that he would be greater than he but he had not known the new kind of his greatness: It consists in humility, in love, in the Cross, in the value of hiddenness, in the silence which Jesus, as the one who is even greater, is lifted up as the greatest in the world. In the end, the truly great does not lie in the size of the physical dimensions but in what is no longer measurable through them. In truth, what is great by physical quantities is only a preliminary form of magnitude. The real and the highest values occur in this world precisely under the sign of lowliness, hiddenness, silence. The great thing about which the destiny and the history of the world hangs is that which appears small in our eyes. In Bethlehem, God, who had chosen the small, forgotten people of Israel as His people, finally made the sign of littleness the decisive sign of His presence in this world. It is the decision of the holy night – the faith – that we accept it in this sign and trust it without grumbling; accept him – that is: to subject ourselves to these signs, the truth and the love, which are the highest, godlike values and the most forgotten and geräuschlosesten at the same time.***

Finally, let me tell you a story from Indian mythology, which has surprisingly anticipated this mystery of the divine littleness. In one of the myths surrounding the figure of Vishnu, it is reported that the gods had been overpowered by the demons and had to watch them distribute the world among themselves. Then they see a way out: they requested only as much land from the demons as the tiny dwarf–like body of Vishnu could cover. The fiends agreed with that. But they had not known one thing: Vishnu, the dwarf, was the sacrifice that penetrates the whole world, and so the world was redeemed through him to the gods. When one hears this, it sounds like a dream in which, through the confused perspective of the dream, one senses the form of the real. As a matter of fact, it is the tiny reality of the sacrifice, of vicarious love, that turns out to be stronger than all the might of the strong, and that with its littleness in the end pervades and transforms the entire world. In the Child of Bethlehem, this invincible power of divine love is drawn into this world. This Child is the only true hope of the world. But we are called to take the risk with him; to entrust ourselves to the God who made the small and the lowly as His sign. Our heart, however, is said to be filled with great joy that night, for despite its appearance it remains true: Christ the Saviour is here.