Father Richard Thomas, the Jesuit who spent four decades serving the poor along the United States–Mexico border, has taken a significant step toward canonisation after the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops voted to advance his cause.

The decision, made at the bishops’ meeting in Baltimore, draws national attention to a priest whose radical simplicity, intense spirituality and tireless charity marked him out as a distinctive presence in one of the poorest regions of the continent.

The request was introduced by Bishop Peter Baldacchino of Las Cruces, who described Thomas as a man who lived the Gospel with disarming literalness. He quoted Christ’s exhortation: “When you hold a lunch or dinner, do not invite your brothers or your relatives or your wealthy neighbours … invite the poor. Blessed indeed will you be, for you will be repaid at the resurrection of the righteous.”

Thomas, he said, “gave witness to those words of the Lord through a life dedicated to serving persons in need”. His ministry reached across El Paso, Las Cruces and deep into Ciudad Juárez, where he became known simply as “Padre Thomas” among families surviving in the harshest conditions.

Born in Florida in 1928, Thomas entered the Jesuits at 17 and was ordained in San Francisco in 1958.

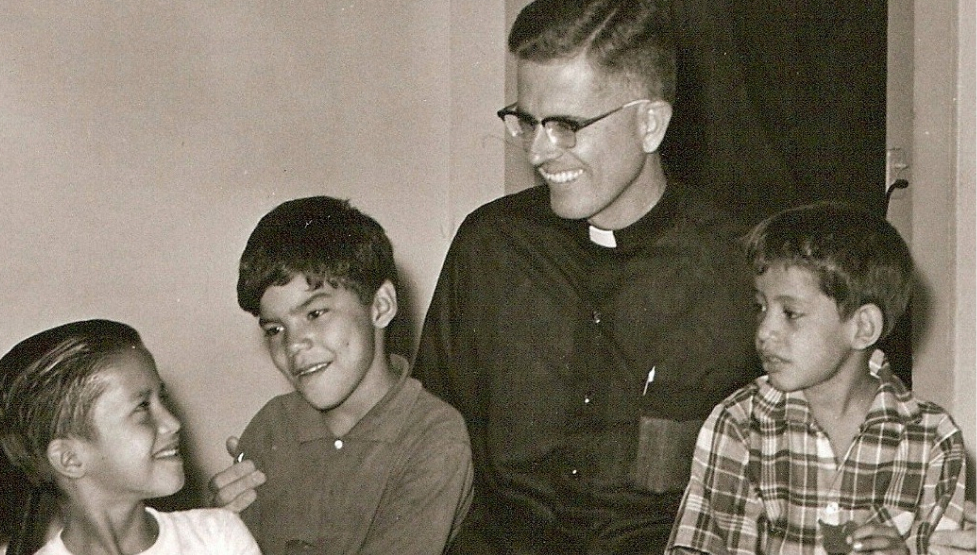

After arriving in El Paso in 1964, he took charge of Our Lady’s Youth Center and steadily expanded it into a wide network of charitable work: food banks, medical and dental clinics, schools for children with no access to education and pastoral outreach in prisons and psychiatric hospitals.

In 1975 he founded The Lord’s Ranch in New Mexico, which became both a refuge for troubled young people and a base for distributing food and supplies across the region.

Bishop Baldacchino noted that Thomas lived with the same stark poverty he saw every day. “He slept in a small room with very few furnishings that included a desk, a chair and an army bed,” he said. “There was no carpeting, no air conditioning and no heating.”

For Thomas, this simplicity was inseparable from faith. “When you minister to the poor, you minister to me,” he often said, convinced that Christ was encountered most directly in those who suffered.

One episode from Christmas Day 1972 has become central to local devotion. Thomas and a small group of lay Catholics prepared food for about 150 people living on a rubbish dump in Juárez, responding to the Gospel command to invite the poor.

Nearly twice that number arrived. “Much to their surprise, everyone had more than enough to eat,” Baldacchino recalled, “and in fact, when the meal was over, they donated leftovers to two orphanages.”

Only now, as his cause advances, are Catholics beyond the border region beginning to engage with the complexity of his legacy.

America Magazine observed that discussion of Thomas has often touched on tensions surrounding the pre-conciliar Church, noting that a major obstacle to his canonisation has been the perception that he was a pre-Vatican II figure whose views did not always align with later reforms.

Mr Dunstan captured the difficulty of categorising him. “Rick Thomas isn’t an easy man to get a handle on,” he wrote. “Was he an old-fashioned pre-Vatican II Catholic or a radical, a barrio politician in a Roman collar or a supernaturalist fanatic, a slave-driver or a clown?”

In the end, Dunstan suggested, one constant remained unmistakable: Thomas would “go to absolutely any lengths to do what he believed God wanted him to do”, and “he was convinced that God had zero concern about how crazy it looked.”