The resignation of Cardinal Timothy M. Dolan as Archbishop of New York and the appointment of Bishop Ronald A. Hicks of Joliet as his successor is more than a routine episcopal transition. It marks the close of a highly distinctive chapter in American Catholic leadership and opens a period of recalibration for one of the Church’s most influential sees.

Today's announcement brings to an end Cardinal Dolan’s nearly 17-year tenure in New York and more than two decades at the forefront of U.S. Catholic public life. At the same time, it elevates a comparatively low-profile Midwestern bishop into a role that carries disproportionate symbolic, pastoral, and political weight within the American Church.

Cardinal Dolan’s retirement at age 75 follows canon law, but its significance goes well beyond procedural norms. Few American bishops of the past quarter-century have been as publicly visible or as influential across ecclesial and civic spheres. His tenure coincided with some of the most turbulent years in modern Catholic history: the intensification of the clergy abuse crisis, mounting legal and financial pressures on dioceses, and escalating conflicts over religious liberty and moral teaching in the public square.

Dolan’s leadership style was unmistakable. Jovial, rhetorically confident, and media-fluent, he became a familiar presence not only in Catholic institutions but in American political and cultural life. As president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops from 2010 to 2013, he led the episcopate during a period of heightened confrontation with federal authorities, particularly over mandates touching on contraception and conscience protections. His insistence on framing these disputes as questions of religious freedom rather than partisan politics helped shape the bishops’ public strategy for a decade.

At the same time, Dolan resisted being boxed into ideological categories. His insistence on engaging both major political parties, exemplified by his participation in both Republican and Democratic national conventions, reflected an effort to preserve the Church’s independence in an increasingly polarised environment. Under his stewardship, New York’s Al Smith Dinner retained its role as a rare civic forum where political leaders from across the spectrum gathered under explicitly Catholic auspices.

Yet Dolan’s legacy is also inseparable from unresolved institutional challenges. Like many American bishops, he governed during a period when historical abuse cases continued to surface, leading to massive financial liabilities and ongoing scrutiny of past episcopal decision-making. As he departs, the Archdiocese of New York faces mediation with approximately 1,300 abuse claimants and the daunting task of raising hundreds of millions of dollars to fund settlements.

Into this complex landscape steps Archbishop-designate Ronald A. Hicks, whose pastoral and administrative formation differs markedly from that of his predecessor. Hicks brings with him a reputation shaped less by national prominence than by close, consultative diocesan leadership.

Since 2020, Hicks has led the Diocese of Joliet, a suburban and semi-rural diocese far smaller than New York but not without its own challenges. There, he oversaw parish restructurings driven by declining attendance, aging infrastructure, and clergy shortages — familiar pressures across much of the U.S. Church. His tenure has also unfolded in the shadow of past abuse cases, though the major settlements in Joliet predate his arrival.

Those who have worked closely with Hicks describe a prayerful leadership style and a man of personal presence and attentiveness to consultation. Rather than projecting authority primarily through public platforms, he has cultivated a reputation for listening, asking questions, and remaining visibly available to clergy and laity alike. His pastoral letter on discipleship, issued in Joliet, emphasised conversion, sacramental life, and missionary engagement — themes closely aligned with Pope Leo XIV’s broader ecclesial priorities.

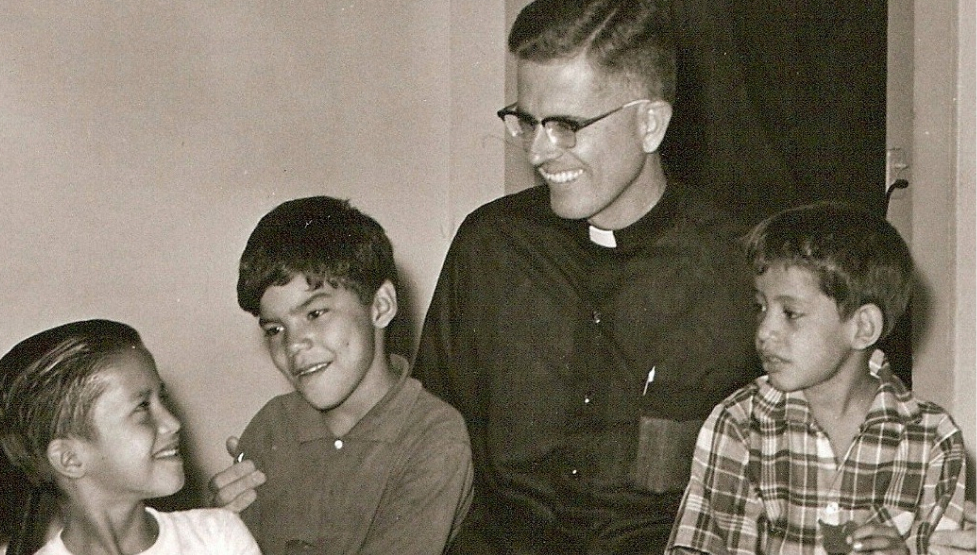

Hicks’ background also includes significant international experience, notably his years in Central America with Nuestros Pequeños Hermanos, a Catholic organisation caring for orphaned and abandoned children. That experience, along with his work in priestly formation at Mundelein Seminary and service as vicar general in Chicago, suggests a bishop shaped more by internal Church formation and pastoral administration than by national political confrontation.

In his statement to the faithful, Cardinal Dolan struck a characteristically warm and conciliatory tone, pledging cooperation with his successor and continuity rather than rupture. His decision to remain in New York as apostolic administrator until Hicks’ installation in February 2026 further signals an orderly transition.

Yet the contrast between the two figures is difficult to miss. Where Dolan embodied a generation of bishops formed during the St John Paul II era — confident in public confrontation and comfortable in national media — Hicks appears representative of a newer cohort: more reticent in public posture, more focused on internal affairs, and perhaps less inclined to dominate the cultural conversation.

Whether this represents a strategic shift by Pope Leo XIV remains to be seen. What is clear is that New York’s next archbishop will inherit an archdiocese facing serious financial, legal, and pastoral pressures, alongside the ongoing challenge of evangelisation in a deeply secularised urban environment.

The transition thus raises broader questions about the future direction of U.S. Catholic leadership. As figures like Dolan step back, the Church may be moving towards a more inwardly focused style of governance — one that prioritises rebuilding trust, fostering discipleship, and managing institutional complexity over high-profile engagement in national and cultural issues.

For now, the Church in New York, and across the United States, stands at a moment of generational change. The success of that transition will depend not only on personalities, but on whether the Church can integrate moral clarity and institutional accountability in a landscape that has grown less forgiving and more fragmented with each passing year.