On a training placement in a UK state school I found much to admire among the pupils and teachers. But compared to the Greek schools where I am usually employed, there was one area where I thought the British had got it wrong, and that was with school uniforms.

For the British teachers, it had resulted in a sort of mumbled corridor mantra: tuck in your shirt, tuck in your shirt. It was a losing battle and not even an honorable one, only making teachers look silly and ineffectual. Formal clothes work well when you want to look good and formal. When not, it’s worse than athleisure wear. Almost.

In Greece, schoolchildren are generally free to wear what they want. There is an irony here as the result is more uniform (in the adjectival use). The Hellenic Education Ministry could claim to have a dress code, at least for boys, as it is one they proudly wear outside of school as well. You likely know it already, as it appears to be ubiquitous across adolescent Europe: a black hoodie (with or without gilet), black shorts or tracksuit bottoms, black trainers.

Here it has less of a gang-related roadman aspiration and is attributed more to a Balkan influence, but it looks largely the same. Acceptable brands are Nike or Adidas or The North Face, the logos and letters the only intrusion of white. Combined with buzzcuts, the pallor of energy drinks and 3 a.m. Instagramming (or worse), the overall effect is to turn the wearer into a shambling eyesore, though given that they are teenagers, that’s probably the idea.

Morning assemblies are like a review of communist-block orphans forcibly apprenticed to a sporty undertaker. When I ask why this sartorial micro-aggression, the kids become awkward, citing comfort, ease of matching and nonsense about being less likely to be targeted at night. (Though in some ways this is indisputable: I have nearly run down several, who are practically invisible on the unlit streets in their after-dark prowlings.) The truth, from what I gather, is that they are ostracised and mocked if they dress in any other way.

But maybe the hive-mind has a good reason for enforcing this generational solidarity.

Since Genesis, how we cover our nakedness does matter. And since black has been an available colour to humans, it has carried the same connotations: death, misery, violence, secrecy and anonymity.

Along with this it claims an ersatz moral gravitas. The wearer is more serious than the world of colours. He or she is not flippant, not trivial – no, no, the black-wearer is on nodding terms with the abyss and in a state of impervious nihilism. From Hamlet to Kanye West, men in black have always been a spiritual buzzkill, a vibe-harsher, spoiling it for all around them.

It’s no coincidence that for jihadists, Nazis and any would-be dominator – physically or psychically – the best colour has always been no colour. Being miserable and forbidding stands in for genuine engagement with the world, and black is their go-to hue.

In the Bible, those who proclaim the kingdom of God – as we all should – wear happier duds. Angels appear in bright raiment, and The Book of Revelation describes the colours of the Heavenly City, showing the Church headed towards glorious polychromatism: “to her it was granted to be arrayed in fine linen, clean and bright, for the fine linen is the righteous acts of the saints” (Revelation 19:8).

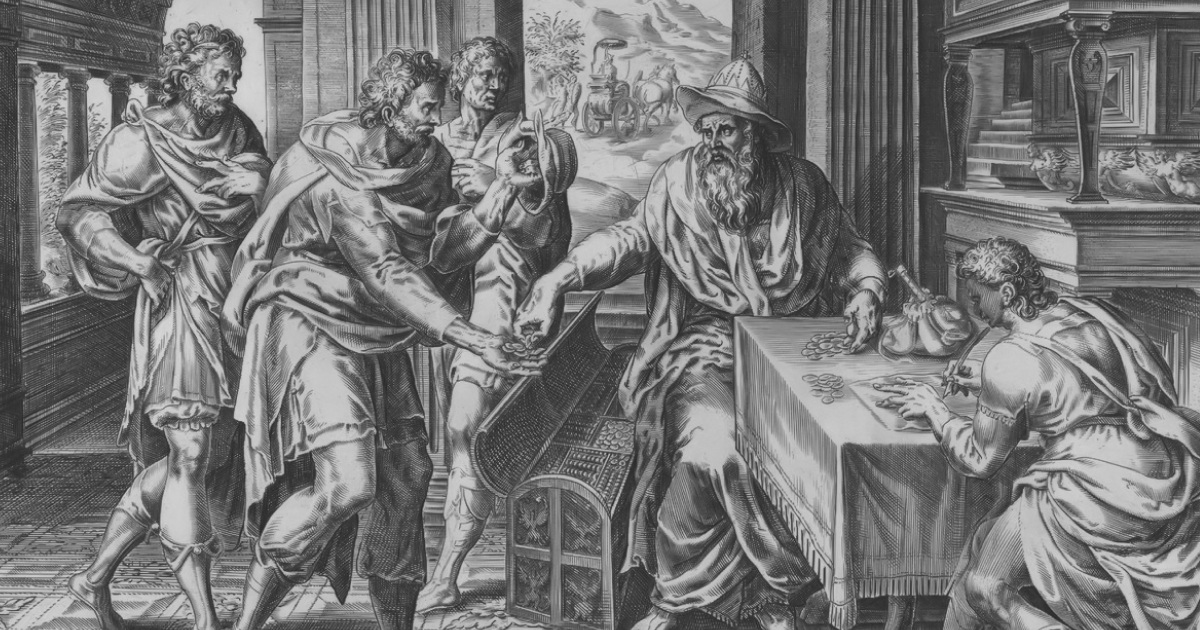

Joseph’s coat was of many colours, which Dolly Parton reframed as her own motif of loving poverty. Priests wear gorgeous stuff while celebrating Mass.

But lately, my maturer exasperation with the gloomy platoons of the Nike Youth has begun to feel unjust and inadequate. Despite the deliberate, depressing depersonalisation of their appearance, this does not seem to be an indication of an inner condition. The kids are actually pretty sweet and kind, which strikes me as remarkable, considering the catastrophe of the world within which they are coming of age.

Compared to my memory of being a teenager, which was far from a time of unallayed bliss, theirs looks unbearably sad. Ever more tested and graded, with less and less freedom and play; joy and authenticity sucked out of life by smartphones and AI; facing precarious employment and savage income inequality, with university both expensive and useless; their identities pushed towards a false dilemma of doltish reaction and scolding wokery – a pervading godlessness – it all makes me wonder if the dressing in black might be a collective, subliminal, inarticulate cry for help.

Or that it constitutes a kind of proleptic mourning for the death of their future, set to be a drab, digitised grind; or, it’s a choice of necessity, some kind of covert operation or hustle, avoiding surveillance or recognition.

All that nihilistic polyester constitutes a bleak, opaque mirror held up to their own generational prospects – and to us, their supposed elders and betters.

However much I would like them to cast off such nighted wear, and even if I refuse to have it in my own wardrobe, I am also prompted to think of Johnny Cash’s lament:

“But 'til we start to make a move to make a few things right / You'll never see me wear a suit of white.”