Imagine a large house in London, home to three generations of Catholics, each of them poets, novelists, critics, publishers, artists. The drawing room is the scene of regular salons, where writers from across Britain and the world gather to read and discuss their work. Together they are shaping modern literature, seeking to express their vision of God in the most startling and beautiful forms.

That house was 47 Palace Court in Bayswater; the family were called Meynell. Presiding in the drawing room was Alice, a tall, large-eyed beauty, the subject of many drawings and paintings: she embodied all the aesthetic ideals of the early 20th century.

Alice Meynell was born in 1847, the daughter of painter and pianist Christiana Thompson. The family were devout Anglicans until Alice began to read Newman and, aged 21, converted to Catholicism. Soon her entire family followed.

Meynell was already a recognised literary talent: when she described the interior change of conversion she inverted the usual image of the Church calling her soul. Instead, she wrote that it was "I who received the Church so that whatever she could unfold with time she would unfold it there where I had enclosed her, in my heart."

In 1876, Alice married writer, publisher and convert Wilfrid Meynell. The couple settled in Bayswater where they had eight children, edited and printed numerous periodicals (Merry England, The Pen, Weekly Register), and opened their house to writers both Catholic and non-Catholic: Francis Thompson, DH Lawrence, Aubrey de Vere, Coventry Patmore, George Meredith, GK Chesterton and Harriet Munroe.

They gathered to read aloud, edit each other's work, argue about style. Among them sat artists John Singer Sargeant, Sherril Schell and early photographers Walter Ernest Stoneman and EO Hoppé – all busy capturing portraits in order to record their historical moment, the fierce re-emergence of a British Catholic literary world after centuries of suppression.

Meynell herself was a celebrated poet (collections included The Flower of the Mind and A Father of Women). She also wrote volumes of short, elegant essays (The Spirit of Place, London Impressions, Hearts of Controversy) on topics both literary and common to daily life: rain, composure, solitude.

The essays widely read at the time emerged from Meynell's experience of foreign travel, her analysis of Greek myth, her observations of nature; they directed a lightly philosophical eye to the ordinary and particular. The essays are rarely bitter or argumentative, except for one, written after Guy Fawkes Day, in which she criticises the angry carnival of British idolatry: "mockery is the only animating impulse, and a loud incredulity the only intelligence".

Meynell's prodigious literary output did not diminish her commitment to social action. She campaigned against the Boer War and the First World War and, while other prominent Catholic women (such as Josephine Ward) remained critical of the suffrage movement, Meynell was a founding member of the Catholic Women's Suffrage Society.

She established and edited The Catholic Suffragist, in which she wrote "of all the crying evils in the depraved earth the greatest, judged by all the laws of God and humanity, is the miserable selfishness of men that keeps women from work".

Meynell's literary reputation in the early 20th century was well established: why has her work been forgotten? It could be argued that her main genre, the essay, fell from favour after the wars and yet the essays of Virginia Woolf remain widely in print.

Meynell's essays are as taut and observant as Woolf's, and in many ways more expressive of the period in which she lived: their literary and historical value is as important today as it was during her own life. And why has her poetry been neglected when that of Christina Rossetti is routinely taught in English literature courses?

Did she disappear from the literary canon because she was a Catholic woman? This explanation seems too easy. Even in the early 20th century, when the same prejudices existed, Meynell was sufficiently well regarded to be twice considered for Poet Laureate, once at the death of Tennyson in 1892 and again in 1913. She would have been the first woman and the first Catholic ever to take the role.

The Bayswater house still stands. A blue plaque bearing Meynell's name marks the front porch. Go there and listen closely: you might hear the distant echo of those raucous arguments, the drinking and reading aloud, the leafing through new volumes, and behind it all the clanking of the printing press.

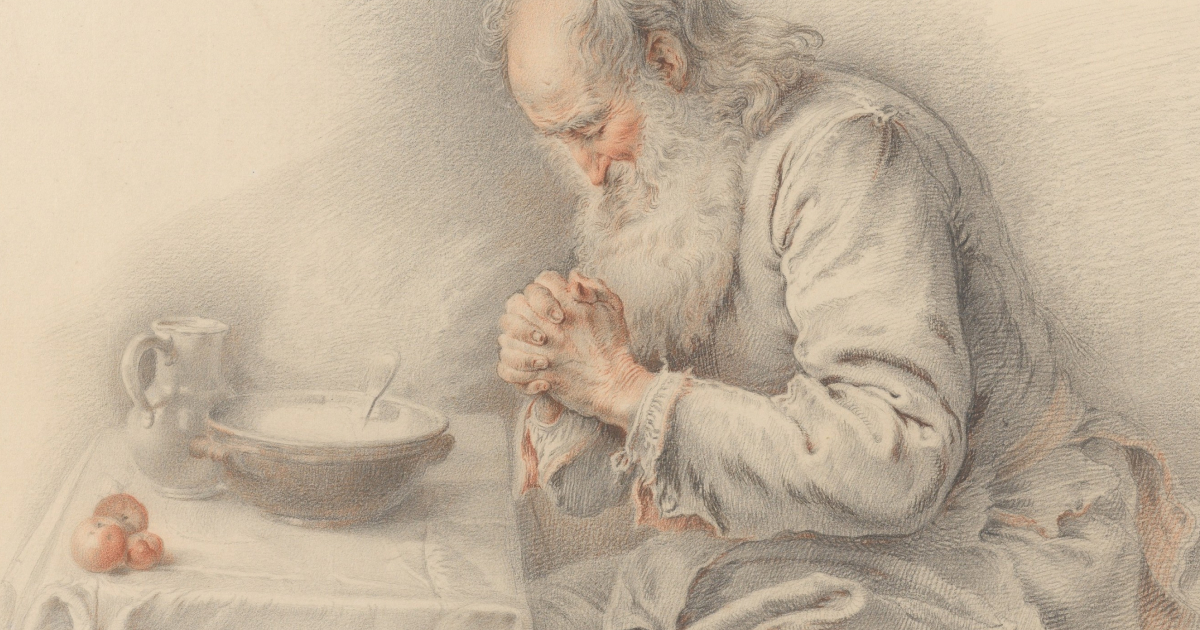

At night, after their guests had dispersed, Wilfrid and Alice Meynell would gather their thoughts and talk through everything they had heard, planning the next week's work. The couple valued especially these more intimate, after-party conversations in which Alice, the socialite, became listener and the more pensive Wilfrid could offer his reflections on the day. Alice would later write of their more quiet, gathering-in discussions, in her poem "At Night":

Home, home from the horizon far and clear, / Hither the soft wings sweep; Flocks of the memories of the day draw near / The dovecote doors of sleep. Oh, which are they that come through sweetest light / Of all these homing birds? Which with the straightest and the swiftest flight? / Your words to me, your words!

Will there ever be another such house for British Catholics to gather?

Photo: graphic with Alice Meynell (by Arcadia)

Bonnie Lander Johnson is a fellow in English at Downing College, Cambridge University

This article appears in the October/November 2025 edition of the Catholic Herald. To subscribe to our thought-provoking magazine and have independent, high-calibre and counter-cultural Catholic journalism delivered to your door any where in the world click HERE.