“Beauty is a manifestation of secret natural laws, which otherwise would have been hidden from us forever,” wrote Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, reminding us that the human heart longs not merely to understand but to behold.

Beauty, truth, and goodness – those classical transcendentals – have always needed a home, a place where the intellect and imagination can meet, where art is more than ornament and theology more than theory.

Oxford has long been such a place. From the medieval Schoolmen to the Inklings gathered at the Eagle and Child (soon to be re-opened), the city has been a crossroads of faith, learning and artistic creativity. Today, a new initiative seeks to continue that living tradition: the Centre for Theology and the Arts at Blackfriars Hall, University of Oxford.

Founded under the guidance of Fr Dominic White OP, prior of the Dominican Community in Oxford, the centre aims to restore dialogue between art and faith at a time when beauty has been politicised, thinned or misunderstood. Rather than reducing art to ideology or mere decoration, Fr Dominic hopes to re-open the space where the arts can draw the soul toward transcendence – gently, silently and yet with great force.

The centre is emerging at a providential moment: Oxford’s new Schwarzman Centre for the Humanities has broadened space for interdisciplinary dialogue, and the hunger among young people for spiritual meaning has become increasingly visible.

For Fr Dominic, this is not simply a cultural project but an apostolate: a way of welcoming the seeker through the doorway of beauty long before explicit theology begins.

What follows is a conversation about the vision behind the centre – why beauty matters, how art can open us to the divine, and why the Church must remain an active patron of the imagination if she is to speak convincingly to the modern world.

Catholic Herald: Oxford has long been a meeting place for faith and imagination – one thinks of the medieval scholastics, then of Lewis and Tolkien. Will the new Centre for Theology and the Arts continue or perhaps re-enchant this tradition today?

Fr Dominic White: I think it comes at a moment of real opportunity. Just this September, the Schwarzman Centre for the Humanities opened its doors. Both the building and its first years of programming have been funded by an American donor. It is, architecturally, a very fine building – an elegant meeting of the modern and the traditional. It doesn’t look like one of those generic university blocks that could have been taken from an airport design; it has character.

People are already using it – the café, the public spaces. Several humanities faculties are based there, and later this year there will be performances and exhibitions. So the cultural life of Oxford is not diminishing; if anything, it is expanding.

St John Henry Newman would approve of this, because he always insisted that the university should avoid the dangers of over-specialisation. The descent into silos has only been amplified by our algorithmic culture. But now, we again have theology in dialogue with philosophy, literature, the arts – a genuinely interdisciplinary environment.

The aim of the Schwarzman Centre is to create an interface between the university and society through the arts, with real performances by real artists. Even before the launch of our own centre, I was already in conversations about this.

And at a deeper level – whatever people believe – no one can live solely on the basis of scientific materialism. We need more. We need beauty. The German word Geist is helpful here: it means “spirit”, but also the whole non-material dimension of reality – those things we cannot live without.

Politics, for example, isn’t material, yet without it we cannot have a society. Although I would be critical of Hegel or Kant in many respects, that insight into Geist is important.

CH: Another exciting thing about the arts is simply that they start conversations?

DW: If I put up a poster – “Does God Exist? Lecture Tonight” – some people would come, certainly. And I can attest to that, because at Blackfriars we have that kind of discussion. And maybe more interestingly, many young people are thoroughly fed up with liberal secularism.

In a strange way, Catholicism has actually benefited from secular liberalism: we are no longer the tolerated minority while Anglicanism is the dominant establishment. Now we are more or less on equal footing, and the Anglicans are very nice to us [laughs].

By the same token, this rampant secularism has created a moral desert. It is parasitic on Christian values in order to function. So we are at a time of crisis, but also of opportunity. Many young people are returning to the faith; others are simply curious. They may not come to a lecture on the existence of God – but put on an event with Shakespeare, with art, with music, and they will come.

For our first seminar at the centre, “War, Peace, and Shakespeare” – which followed the launching event on the Aesthetics of Jacques and Raïssa Maritain – people came whose religious views I simply do not know. Michael Scott gave a marvelous contextual introduction to Shakespeare’s world – medieval mystery plays and morality plays, the liturgy, the echoes of the Mass in his dramatic form. I did not know parts of this myself, and it was thrilling.

Three volunteers – one of our students and two members of the public – perform a scene from Henry IV, where in the Wars of the Roses a father realises he has killed his son, and a son realises he has killed his father, while the king stands between them. It was astonishingly powerful and touching.

This is the sort of thing that can begin a conversation – rigorous yet hospitable, intellectually serious yet unthreatening.

Two of our great models are the French Catholic intellectuals Jacques and Raïssa Maritain, who excelled in hospitality. Many who crossed their threshold later became Catholics. So yes – it is a great opportunity.

CH: What about beauty: Is beauty not a debated concept?

DW: I am not pushing the word “beauty” too hard at the moment because it has become contested. If I marketed the Centre explicitly as a centre for beauty, some might think we are doing cosmetic surgery! Beauty has also become contested because some say it is mere prettiness avoiding ugliness. That is to say: Beauty will emerge naturally. It is one of the transcendentals – along with truth and goodness. We cannot avoid it.

And then you get questions: “What is beauty?” Then Photoshop culture – the “Instagram face” phenomenon. My second book was actually on theology and the selfie. Some people become mentally unwell because they doctor their images to match an artificial ideal, which garners likes, and yet internally they know it is false.

There is a lot of work to be done on recovering real beauty, which ultimately is the radiance of God.

CH: Would you agree that contemporary art risks being too “cerebral” at large, that it touches on the mind only – if that – leaving the whole person out?

DW: A lot of modern art speaks only to the mind – or claims to. But, we are not only intellect; we are whole persons.

Good art should speak for itself. People sometimes say religious art is “kitsch”, just illustration. But there is much contemporary art that surprises me, touches me, makes me think – because it has real artistic content.

I always try to visit the Berlin Biennale. 2022 was really disappointing, but this year one piece – a sound collage – was remarkable. The artists made poems from things overheard on buses and trams, in pubs and cafés.

It made you think about society – the words people repeat, what they reveal. Very moving. That is art doing what Maritain described: the artist is the intellectual who makes. Thought embodied.

Often contemporary works are overshadowed by an expository text full of fashionable vocabulary – “interrogate”, “ironic”, etc. But occasionally one finds something genuinely arresting.

CH: Does the centre address the loss of transcendence in modern society?

DW: We have certainly reached a crisis point. Some humanities departments have begun asking theology faculties if their students may attend Bible courses in order to get to know the texts and stories of which the biblical frescoes or sacred art speak, because they have no idea.

They don’t know why someone has a halo – or what that even is! This is an opportunity. But rather than lecturing about transcendence, the better way is to let the art speak, in my experience. Give people an artwork that moves them – that draws them into the deeper reality.

French philosophy, much of it indirectly shaped by Christianity, speaks of “excess”: that every phenomenon contains more than we can define. You can look at your favourite tree and always see more. Some philosophers now avoid the word “transcendence” – too religious – and say “excess” but the instinct is similar. So yes – give people the artwork; then begin the conversation.

This echoes the mystical way – think of the Cloud of Unknowing, or John of the Cross: You are to go by a way that you do not know.

I pray for the work of the centre. Others pray for it. I am excited to see how God will surprise people who are hungry for beauty, even if they cannot articulate that hunger.

CH: Was there a moment, earlier in your life, when art opened the door to another reality?

DW: Absolutely. As a teenager, thanks to my music teachers, I discovered 20tht-century French organ music – especially Olivier Messiaen. It blew my mind. His music did not sound like anything else: utterly contemporary, yet deeply Catholic.

Much of his work meditates on the Resurrection, on heaven. Messiaen famously said he could not wait to get to heaven and see what it was really like – and God granted him that in the early 1990s.

As more of his life has been studied, his holiness has become increasingly clear. That profoundly influenced my own work as a composer.

I have just finished a nocturne based on one of the Advent antiphons from the English Dominican Vesperale. I will premiere it shortly at Newman’s College in Littlemore, at an event hosted by the Sisters of the Work of God, marking the launch of the English translation of Fr Helmut Geisler’s short biography of Newman.

CH: How do you find artists and participants for the centre?

DW: Mostly through personal connection and recommendation. Above all, they must be able to work collaboratively. The Romantic idea of the tortured, isolated genius starving in a garret – I think that is ending.

In the Middle Ages, the artist was a craftsperson with a respected role in society. Most worked on commission, often for churches. Originality was not the primary value; yet each had a personal style. Anyone can distinguish Fra Angelico from Duccio.

Today many artists are lonely; that’s why increasingly they work in collectives. That can be an opportunity. Most of our contributors this year are Christian, and most of those are Catholic. Many are connected to Blackfriars, or part of our wider community.

We are also blessed to know Sir James MacMillan, who gave the keynote at the Maritain conference. He is a world-renowned composer and public intellectual, and exemplary.

CH: The Church has historically always taken the place of a great “patron of the arts but this seems to be largely forgotten. Why do you think this is so?

DW: Historically, the Church has been a patron of the arts – music, painting, architecture. In the twentieth century, there was a growing divergence between artists and the Church. Popes such as Paul VI and John Paul II – himself an actor – recognised this.

In France, Dominican Fr Marie-Alain Couturier befriended major modern artists – Picasso, Brancusi, Matisse, Le Corbusier. He and Sr Jeanne-Marie commissioned extraordinary works, like Matisse’s chapel at Vence. Controversial, yes – some of these artists were not believers, and some did not fully understand the purpose of a church – but some of the works were remarkable.

Elsewhere, the effort to commission contemporary artists continues. Some of these artists are drawn to mysticism or non-religious spiritualities; some drift toward the occult; there have been naïve choices and serious mistakes. One must accompany artists carefully.

If we want Catholic artists of the highest calibre, we must form them. There are excellent examples today – Aidan Hart, Martin Earle, Sir James MacMillan – but art costs money, and many parishes are poor. One must pay artists properly if one wants good work.

CH: Which art speaks today?

DW: People say we live in a visual age – but upon closer inspection places like YouTube are not purely visual; it is image, language and motion. We are multi-sensory beings.

Therefore, I would not place all our hopes on one medium. The Church should be present in every art form. If we withdraw, we effectively surrender territory to the devil: “Here, have it – Happy Christmas.”

When I served as chaplain to artists in Newcastle, we worked across all art forms. One Catholic choreographer created a piece called "Missa", inspired by the gestures of the Mass and the processions. One of his dancers was the last Catholic in her family. She said the work brought her back to the Church – she had never connected her love of dance with her faith. Now the two were reconciling.

That is the power of art.

CH: Thank you for your time, Fr. Dominic.

DW: You’re welcome. It is an exciting time!

RELATED: A haven of faith and literacy: St Philip’s Books in the heart of Oxford

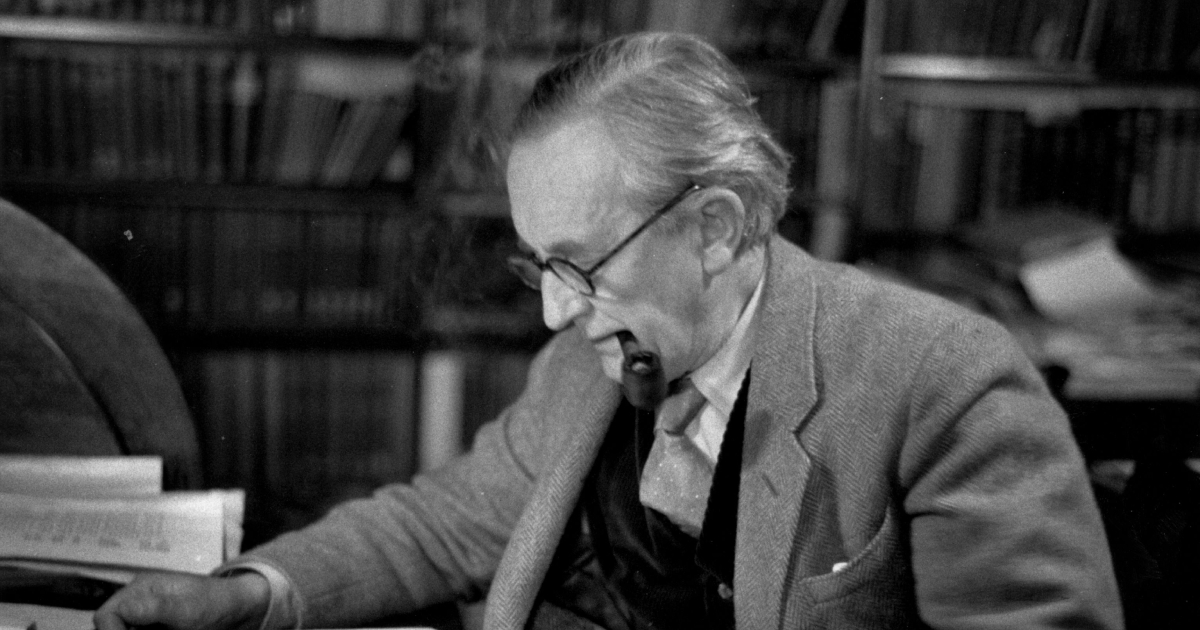

Photo: Fr Dominic White OP (credit: Richard Brown)

More information on the new Centre for Theology and the Arts, Blackfriars, can be found here