The Mennonites of Canada are often imagined as a people apart: plain-dressed, humble and detached from the messy theatrics of modern politics. For centuries, they have cultivated an ethic of separation, a suspicion of worldly power and a desire to remain, in their own words, “the quiet in the land”.

Historically, Mennonites were recognised as conscientious objectors. It did not make sense to vote on state governance because they were “citizens of the Kingdom of God” and not of any individual country. They would not carry weapons, rarely cast a ballot and preferred tilling fields to stirring politics.

For rulers, this was seen not as a liability but as an asset. Catherine the Great welcomed them to Russia, and Canada in the late 19th century did the same, calculating that these industrious farmers would enrich the soil and never trouble the State with rebellion.

While one can still find Mennonite congregations in rural areas of Canada that abstain from civic life, among the great majority, voting is now not only accepted but expected. So much so that Mennonite convictions have seeped into the bloodstream of political discourse in Canada, shaping not only elections in prairie ridings but the tone of the Canadian conscience itself.

For Catholics, it is a reminder that faith is never purely private. As Gaudium et Spes insists: “The split between the faith which many profess and their daily lives deserves to be counted among the more serious errors of our age."

Mennonites have refused such a split. Their convictions on peace, community and conscience flow from their churches into their fields, their towns and finally into their votes. Their politics is not the politics of slogans or spectacle but the politics of witness.

In an age of shrill voices and ideological crusades, the Mennonite influence is profoundly countercultural. It shows that influence need not roar. It can whisper and still be heard. It can remain humble and still shape the common good.

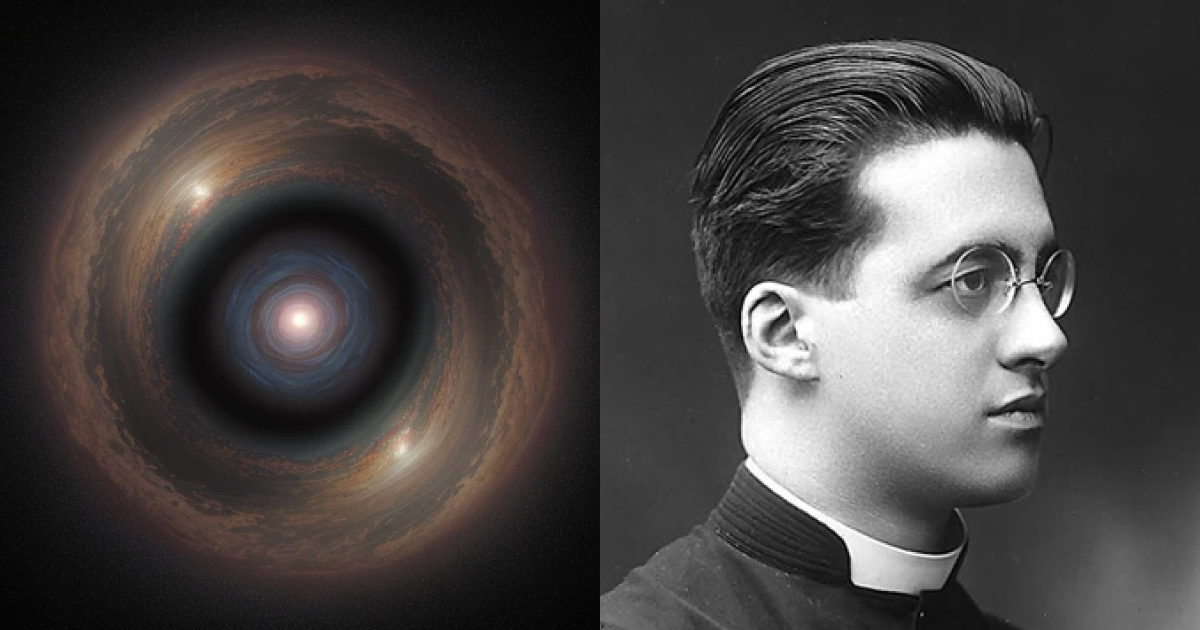

The story behind Mennonites and Canadian politics begins with Erhart Regier, elected in 1953 as the first Mennonite MP. In his maiden speech, he did not speak of partisan manoeuvres but of conscience: urging Parliament to redirect military budgets into humanitarian aid and peacekeeping.

His words were theological before they were political. They reflected Mennonite doctrine, drawn from the Sermon on the Mount, that violence is incompatible with discipleship. At the same time, in a moment which would foreshadow their eventual transformation, Regier challenged his own community not to retreat from civic duty.

His community obliged, increasing democratic participation tenfold within a couple of decades. In the 1970s, Jake Epp of Provencher carried this pattern forward. Serving more than two decades in Ottawa and rising to a cabinet position under Joe Clark, he embodied what his Mennonite upbringing had instilled: humility, fidelity and steadiness.

What strikes observers even now is how closely his political style mirrored the ethos of his Church. Constituents did not look for grandstanding or celebrity; they looked for integrity. Theology became politics, not through sermons from the pulpit, but through Epp’s demonstration of a life dedicated to public service and his consistent promotion of Mennonite teachings in the Canadian House of Commons.

The influence continues today in the region of Portage-Lisgar, home to Mennonite-majority towns such as Winkler and Morden. Long a bastion of conservative strength, the region returned politician after politician for the Conservative Party of Canada. And yet, the riding shifted in 2021 when many Mennonite voters turned toward the more right-leaning People’s Party of Canada, reacting against pandemic mandates they regarded as intrusions upon conscience and community.

To outsiders it would seem a quirk of populism. I would levy that it was something older and deeper: a conviction that conscience belongs first to God, and that the proverbial Caesar is limited in his authority.

Catholics can easily recognise this sentiment. Gaudium et Spes teaches: “Conscience is the most secret core and sanctuary of a man. There he is alone with God, whose voice echoes in his depths."

Mennonites, in their instinctive defence of conscience, find themselves remarkably aligned with this teaching, even if they would not phrase it in conciliar Latin.

Mennonite institutions reinforce the same witness. The Mennonite Central Committee has long pressed governments on peace, refugee resettlement and restorative justice. The Mennonite Church in Canada has spoken against nuclear weapons, capital punishment and State violence, always with reference to the Gospel.

These statements rarely make headlines, but they embody what Gaudium et Spes insists is the Church’s task: "[to] read the signs of the times and interpret them in the light of the Gospel."

The Mennonite contribution, though plain and unadorned, is precisely this – an attempt to live out discipleship in the realm of politics without succumbing to the pursuit of power.

Less vocal and outwardly bible-thumping than their evangelical counterparts in the deep South of America, one might presume modern Mennonites to still be detached from the world’s grubby disputes. But anyone who has spent time in southern Manitoba or rural Saskatchewan knows better.

Mennonite communities have been farming those provinces for generations; they are landowners, small businesspeople and taxpayers par excellence. Their interests are recurrently pragmatic – low taxes, restrained government and a certain suspicion of Ottawa’s latest bright idea. In that sense, one could say they form the backbone of prairie conservatism.

Admittedly, they do not determine election outcomes in Toronto or Vancouver, but in prairie ridings they have been decisive, and their ethos of modesty and conscience has tempered Canadian conservatism. This quiet influence points to a larger truth: that politics is healthiest when it is grounded in moral restraint rather than in ambition.

For Catholics, especially those in the UK now, confronted with a Parliament legislating for assisted suicide and abortion up to birth, it is a powerful reminder about how to balance faith and privacy versus public life.

And it demonstrates, for Catholics as much as for Mennonites, that when the Gospel is lived consistently, it will always be politically consequential.

Photo: A Mennonite choir sings in Dupont Circle. (Ben Schumin.)

%20(2).png)