Every October, the Catholic Church pays homage to two Carmelite saints: Saint Teresa of Avila, the bold sixteenth-century Spanish reformer honoured on October 15, and Saint Thérèse of Lisieux, the humble French cloistered Carmelite known as the Little Flower, remembered on October 1.

Though they lived centuries apart, in different countries and embodied contrasting temperaments and experiences, these two women became spiritual titans and Doctors of the Church, living their lives in divine love and humility.

Feisty, strong-willed, and brimming with courage, Saint Teresa of Avila (1515–1582) was born during a period of political and religious turmoil. Defying her father’s wishes, she entered the convent at 20 and went on to transform the Carmelite order through the Discalced Reform in 1562. Her restless spirit took her across Spain, where, accompanied by Saint John of the Cross, she founded 17 monasteries for women to restore religious life to its former state.

The nickname “the Roving Nun” fitted Teresa perfectly: she was a woman of action, a reformer and a born leader who worked tirelessly for the renewal of a more rigorous Carmelite order. Teresa was not only practical but also intellectual. With conviction and great insight, she wrote her most famous work, El Castillo Interior (The Interior Castle), in which she describes the soul as a castle with seven dwelling places. Each, she explains, represents a stage of prayer leading to the soul’s union with God. The first woman to be declared a Doctor of the Church said: “It is foolish to think that we will enter heaven without entering into ourselves.”

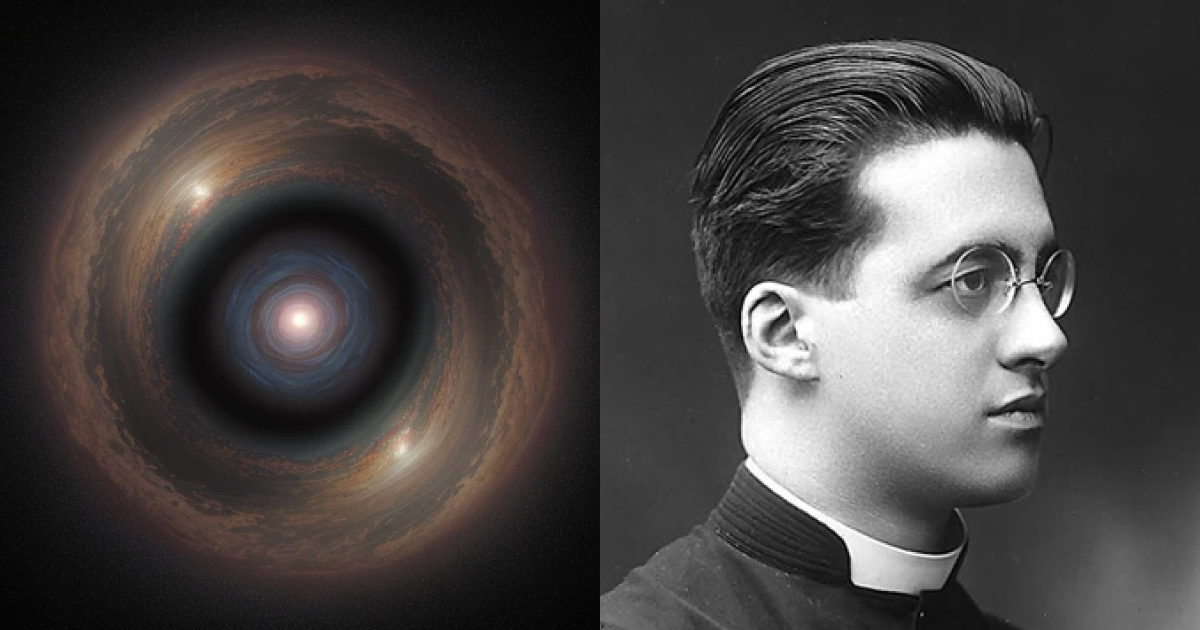

Saint Thérèse of Lisieux (1873–1897), by contrast, lived a quieter life. Born in Normandy to Saints Louis and Zélie Guérin Martin, who were canonised by Pope Francis in 2015, her short life was marked by an earnest desire to become a bride of Christ. She entered the Carmelite monastery in Lisieux at the age of 15, after petitions to her local bishop and Pope Leo XIII himself, and made her lifelong vows at 17. She remained there until her death at 24.

The Little Flower, during her short life, showed that we can love God not through grand gestures but by simple acts of love. Her autobiography, Story of a Soul, written at her superior’s request towards the end of her life, became one of the most spiritually inspiring works of modern times. With humility and tenderness, Saint Thérèse affirmed her total trust in God’s love. When asked about her “little way,” she explained: “It is the way of spiritual childhood, the way of trust and absolute surrender.”

Both women knew pain and suffering. Saint Teresa endured malaria and paralysis, along with fierce opposition from those who resisted her reforms. Saint Thérèse suffered the loss of her mother at a tender age and later the slow agony of tuberculosis. Amid illness and hardship, each in her own way lived with resilience, turning pain into a deeper union with God.

Today, we remember their legacies and how harmoniously they are intertwined. Teresa’s reforming energy and mystical talents complement the simplicity of Saint Thérèse. In Avila, pilgrims will celebrate the “Doctor of Prayer” with solemn processions and joyful feasts. Meanwhile, in Lisieux, this year marks the 100th anniversary of Thérèse’s canonisation, commemorated with spiritual and cultural events honouring her enduring message that holiness can bloom even in the smallest acts of love.

Both Saint Teresa and Saint Thérèse shared the same goal — perfect unity with God through prayer. These two pillars of strength reveal different but radiant paths of spirituality. Saint Teresa is audacious and idealistic, determined to renew spiritual and monastic life in the Church despite opposition. Saint Thérèse is quiet and trusting, her little life of holiness, charity, and sacrifice drawing countless souls to God. Both paths lead to the same destination — the heart of God. As Saint Thérèse wrote, “Holiness consists simply in doing God's will, and being just what God wants us to be.”