Charles Dickens described the Christmas holidays as “a good time: a kind, forgiving, charitable, pleasant time; the only time I know of in the long calendar of the year, when men and women seem by one consent to open their shut-up hearts freely, and to think of other people below them as if they really were fellow-passengers to the grave, and not another race of creatures bound on other journeys” (A Christmas Carol). Without exaggeration or overstatement, then, it could be argued that Dickens has had more influence on how we traditionally celebrate Christmas today than any other individual in history – except one, that is, the central character of the seasonal narrative, Our Lord himself, the Christ whose Mass is fundamental to everything else that might take place.

Dickens wrote a number of Christmas stories and books, some of which have been plundered and part-excavated here. While not every story of his addresses Christmas specifically, the recurring theme of what has been referred to as his “carol philosophy” should be evident throughout, and can be detected between the lines: goodwill, spiritual reflection, our common humanity, and sometimes, reverence and worship. Those strands mingle and mix in the excerpts here.

A Christmas Carol

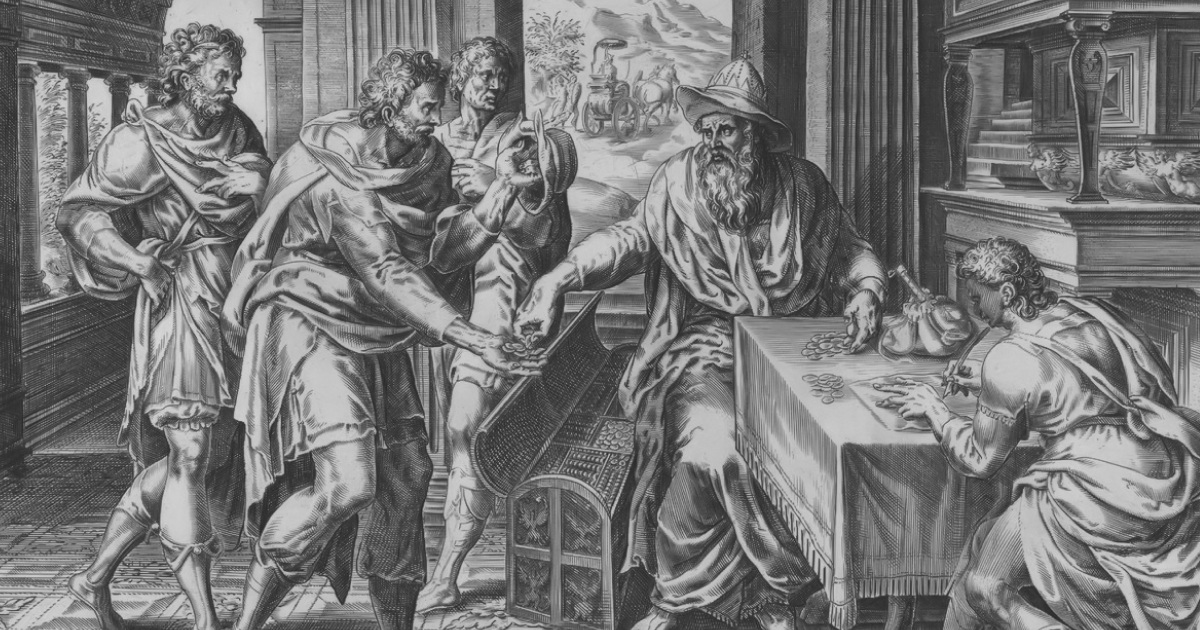

They were portly gentlemen, pleasant to behold, and now stood, with their hats off, in Scrooge’s office. They had books and papers in their hands, and bowed to him. “Scrooge and Marley’s, I believe,” said one of the gentlemen, referring to his list. “Have I the pleasure of addressing Mr Scrooge, or Mr Marley?”

“Mr Marley has been dead these seven years,” Scrooge replied. “He died seven years ago, this very night.” “We have no doubt his liberality is well represented by his surviving partner,” said the gentleman, presenting credentials. It certainly was; for they had been two kindred spirits. At the ominous word “liberality”, Scrooge frowned, and shook his head, and handed the credentials back. “At this festive season of the year, Mr Scrooge,” said the gentleman, “taking up a pen, it is more than usually desirable that we should make some slight provision for the poor and destitute, who suffer greatly at the present time. Many thousands are in want of common necessaries; hundreds of thousands are in want of common comforts, Sir”

“Are there no prisons?” asked Scrooge.

“Plenty of prisons,” said the gentleman, laying down the pen again.

“And the union workhouses?” demanded Scrooge. “Are they still in operation?” “They are. Still,” returned the gentleman, “I wish I could say they were not.” “The Treadmill and the Poor Law are in full vigour, then?” said Scrooge. “Both very busy, sir.” “Oh! I was afraid, from what you said at first, that something had occurred to stop them in their useful course,” said Scrooge. “I’m very glad to hear it.” “Under the impression that they scarcely furnish Christian cheer of mind or body to the multitude,” returned the gentleman, “a few of us are endeavouring to raise a fund to buy the poor some meat and drink, and means of warmth. We choose this time because it is a time, of all others, when want is keenly felt, and abundance rejoices. What shall I put you down for?” “Nothing!” Scrooge replied.

“You wish to be anonymous?”

“I wish to be left alone,” said Scrooge. “Since you ask me what I wish, gentlemen, that is my answer. I don’t make merry myself at Christmas and I can’t afford to make idle people merry. If I help to support the establishments I have mentioned – they cost enough; and those who are badly off must go there.”

A Christmas Tree

I come home at Christmas. We all do, or we all should. We all come home, or ought to come home, for a short holiday – the longer, the better – from the great boarding-school, where we are forever working at our arithmetical states, to take leave, and give a rest. As to going a visting, where can we not go…

On this low-lying, misty ground, through fens and fogs, up long hills, winding dark avenues between thick plantations, almost hidden from the sparkling stars, so out of broad light we go, until we stop at last, with suddenness, at an avenue. The gate-bell has a deep, half-awful sound in the frosty air; the gate swings open on its hinges; and, as we drive up to a great house, the glancing lights grow larger in the windows, and the opposing rows of trees seem to fall solemnly back on either side, to give us place.

At intervals, all day, a frightened hare has show across this whitened turf; or the distant clatter of a herd of deer trampling the hard frost, has, for the minute, crushed the silence too… and so, the lights growing larger, and the trees falling back before us, and closing up again behind, as if to forbid retreated, we come to the house.

There is probably a smell of roasted chestnuts and other good comfortable things all the time, for e are telling winder stories – ghost stories – or more shame for us – round the Christmas fire; and we have never stirred, except to draw a little nearer to it.

What Christmas Is as We Grow Older

Time was, with most of us, when Christmas Day, encircling all our limited world like a magic ring, left nothing out for us to miss or seek; bound together all our home enjoyments, affections, and hopes; grouped everything and everyone around the Christmas fire; and made the little picture, shining in our bright young eyes, complete.

Time came, and perhaps all so soon, when our thoughts overleaped that narrow boundary; when there was someone… wanting to the fulness of our happiness; when we were wanting too at the Christmas hearth by which that someone sat; and when we intertwined with every wreath and garland of our life that someone’s name.

That was the time for the bright visionary Christmases which have long arisen from us to show faintly, after summer rain, in the palest edges of the rainbow! That was the time for the beatified enjoyment of the things that were to be, and never were, and yet the things that were so real in our resolute hope that it would be hard to say, now, what realities achieved since have been stronger!

The Pickwick Papers

As brisk as bees, if not altogether as light as fairies, did the four Pickwickians assemble on the morning of the twenty-second day of December, in the year of grace in which these, their faithfully-recorded adventures, were undertaken and accomplished. Christmas was close at hand, in all its bluff and hearty honesty; it was the season of hospitality, merriment, and open-heartedness; the old year was preparing, like an ancient philosopher, to call his friends around him, and amidst the sound of feasting and revelry to pass gently and calmly away.

Gay and merry was the time; and right gay and merry were at least four of the numerous hearts that were gladdened by its coming. And numerous indeed are the hearts to which Christmas brings a brief season of happiness and enjoyment. How many families, whose members have been dispersed and scattered far and wide, in the restless struggles of life, are then reunited, and meet once again in that happy state of companionship and mutual goodwill, which is a source of such pure and unalloyed delight; and one so incompatible with the cares and sorrows of the world, that the religious belief of the most civilised nations, and the rude traditions of the roughest savages, alike number it among the first joys of a future condition of existence, provided for the blessed and happy!

How many old recollections, and how many dormant sympathies, does Christmas time awaken!

The Mystery of Edwin Drood

Seasonable tokens are about. Red berries shine here and there in the lattices of Minor Canon Corner; Mr and Mrs Tope are daintily sticking sprigs of holly into the carvings and sconces of the cathedral stalls, as if they were sticking them into the coat-buttonholes of the Dean and Chapter.

Lavish profusion is in the shops: particularly in the articles of currants, raisins, spices, candied peel, and moist sugar. An unusual air of gallantry and dissipation is abroad; evinced in an immense bunch of mistletoe hanging in the greengrocer’s shop doorway, and a poor little Twelfth Cake, culminating in the figure of a Harlequin, to be raffled for at the pastry cook’s.

Public amusements are not wanting. The waxwork which made so deep an impression on the reflective mind of the Emperor of China is to be seen by particular desire during Christmas Week only, on the premises of the bankrupt livery-stable-keeper up the lane; and a new grand comic Christmas pantomime is to be produced at the theatre… In short, Cloisterham is up and doing.

Great Expectations

Mrs Joe was prodigiously busy in getting the house ready for the festivities of the day, and Joe had been put upon the kitchen doorstep to keep him out of the dustpan, an article into which his destiny always led him sooner or later, when my sister was vigorously sweeping the floors of her establishment.

“And where the deuce ha’ you been?” was Mrs Joe’s Christmas salutation, when I and my conscience showed ourselves. I said I had been down to hear the carols.

“Ah! well!” observed Mrs Joe. “You might ha’ done worse.” Not a doubt of that, I thought.

“Perhaps if I warn’t a blacksmith’s wife, and a slave with her apron never off, I should have been to hear the carols,” said Mrs Joe. “I’m rather partial to carols, myself, and that’s the best of reasons for my never hearing any.”

A Christmas Carol

“I will live in the Past, the Present, and the Future!” Scrooge repeated, as he scrambled out of bed. “The Spirits of all Three shall strive within me. Oh Jacob Marley! Heaven, and the Christmas-Time be praised for this! I say it on my knees, old Jacob; on my knees!”

He was so fluttered and so glowing with his good intentions, that his broken voice would scarcely answer to his call. He had been sobbing violently in his conflict with the Spirit, and his face was wet with tears.

“They are not torn down,” cried Scrooge, folding one of his bed-curtains in his arms, “they are not torn down, rings and all. They are here, I am here, the shadows of the things that would have been may be dispelled. They will be. I know they will!”

His hands were busy with his garments all this time; turning them inside out, putting them on upside down, tearing them, mislaying them, making them parties to every kind of extravagance.

“I don’t know what to do!” cried Scrooge, laughing and crying in the same breath. “I am as light as a feather, I am as happy as an angel, I am as merry as a school-boy. I am as giddy as a drunken man. A merry Christmas to everybody! A happy New Year to all the world! Halloo here! Whoop! Halloo!”