The exposures of the Epstein scandal have provided another strong reminder that we cannot always take the authorities at their word. That so many of the world’s political and financial elite were embroiled in compromising associations with a child sex trafficker (and possible intelligence operative) urges us to be more vigilant than ever in scrutinising the actions and inactions of the powers that be.

When papal encyclicals, high-ranking clerics and international business leaders all sing from the same hymn sheet at the World Economic Forum, it does not necessarily mean they are wrong, but it is right for us to engage critically with what is being said – and what is not being said. Loud statements regarding climate catastrophes are matched with silence on grave environmental threats that undermine the very future of human life. Nowhere is this mismatch clearer than when it comes to microplastics and their impact on human fertility.

The scale of this industrial pollution, which appears in our daily food and drink and even in the clothes we wear, should be as scandalous as it is threatening. The mainstream press, however, has largely faced this subject with a concerning and conspicuous silence. And while France and the European Union have attempted to ban the hormone-damaging chemical bisphenol A, action from legislators has also fallen short. Peer-reviewed scientific research has confirmed that we are hurtling towards infertility, physiological weakness and chemical emasculation. Catholics should be raising their voices to offset this silence.

There are those who argue that the Church should simply keep its nose out of politics and who object to it addressing topics such as the environment at all. These critics are understandable, but they are wrong. It is not the Church’s primary goal to be political. If a parish homily on a Sunday contains as much about legislation as it does about Christ, grace, sin, salvation and judgement, there is a severe problem. Nonetheless, religion and politics intersect. For incarnate human beings, composed of both body and soul, what affects the one affects the other. Besides, there are legislative, societal and political phenomena that are contiguous with the Church’s teaching, and those that contradict it.

The problem is that Church authorities, particularly under Pope Francis, have ramped up talk about climate change. Wading into environmental issues is legitimate, but if they seek to be in service of mankind, why do they emphasise something that is so distantly relevant and impactful to people’s lives, and the scale and speed of which are so highly disputed? In 2009, Al Gore stated that there was a 75 per cent chance “the entire polar ice cap will melt in summer” by 2016. In 2004, the Pentagon told President Bush that Britain would have a “Siberian” climate and that global warming would terminate civilisation by 2025. None of this has come to pass.

What has happened is that testosterone in men – and consequently human fertility – has been nosediving. As the GQ article “Sperm Count Zero” points out, the decline in fertility shows no sign of relenting. If it continues, we will soon be unable to reproduce at all. The millennia of human civilisation will have come to a slow, then sudden, halt. Inside and outside the Church, the friends of humanity have no excuse for remaining silent. It is high time voices were raised in demanding action to counter this scandalous industrial crime.

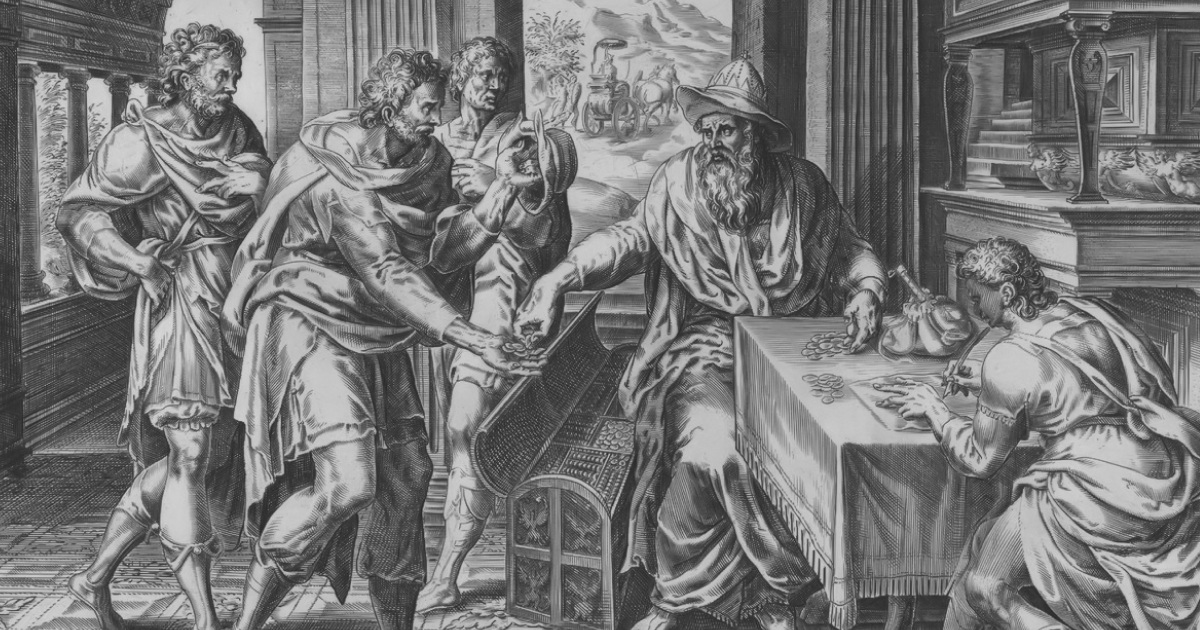

Business is a notoriously predatorial world, and perhaps we should not be too surprised when merchant sharks look for ways to make lucrative profits – even if it swindles or harms the customer – if they think they can get away with it. But the Church has no excuse.

For the ordinary man or woman sitting in a pew, buying groceries, filling a kettle and dressing their children, he or she can no longer trust that the modern world is fundamentally safe. Dangerous substances designed primarily for profit and convenience are now inside our bloodstream, our children’s developing bodies and our homes – chemically, that is, not metaphorically. They wreak havoc in hormonal production, the body’s command system. When that system is disrupted, everything from fertility and energy levels to brain development and cancer risk can be affected. This is a subtle invasion of the body itself.

The collapse in fertility is the most widely recognisable warning sign, but it is still under-reported. A large international analysis of nearly 43,000 men concluded that sperm counts in the West fell by more than half between the early 1970s and 2011 – from about 99 million sperm per millilitre of semen to roughly 47 million. Total sperm counts fell by almost 60 per cent. These numbers are drawn from mainstream epidemiological research. Even scientists initially sceptical have admitted that the downward trend is real. One endocrinologist cited by GQ reportedly looked at the data and said aloud, “No, it cannot be true,” before confirming it repeatedly.

Why should the average man care? Because sperm count is not only about babies. Doctors increasingly treat it as a barometer of overall health. Men with poor semen quality are more likely to suffer heart disease, diabetes and certain cancers. Low testosterone – which has been declining alongside sperm counts – is associated with fatigue, depression, loss of muscle mass and reduced motivation. In simple terms, men are not only becoming less fertile; many are becoming physically weaker and less resilient. For women, endocrine disruption is linked to earlier puberty, fertility problems and an increased risk of certain reproductive cancers. These are showing up in clinics today.

The question is why. Lifestyle factors do, of course, play a role. Obesity, inactivity and delayed parenthood matter. But a growing body of research points to something far more influential: industrial chemicals, often cheap waste by-products of oil refining or chemical processes, that interfere with hormones. Many of these chemicals are found in plastics, food packaging, cosmetics, cleaning products and, especially, processed foods. They are known as endocrine disruptors because they mimic or block the body’s natural hormones – particularly oestrogen. Imagine the body’s internal messaging system receiving thousands of false signals every day. Young boys are ingesting litres of substances each week that load their blood with chemicals behaving like oestrogen. Over time, development is altered, fertility drops and disease risk rises.

Take phthalates, used to make plastics flexible. They are present in food packaging, cosmetics, detergents and even medical tubing. Studies have found that pregnant women with higher phthalate exposure are more likely to give birth to boys with shorter anogenital distance – a marker linked to reduced testosterone and lower fertility later in life. Bisphenol compounds such as BPA, used in plastic containers and can linings, also mimic oestrogen in the body. They have been associated with altered reproductive development, metabolic disorders and potential cancer risks.

Yet when regulators banned BPA in some products, manufacturers often replaced it with similar compounds such as BPS, which early research suggests is no better and behaves almost identically. While public, ecclesial, journalistic and political attention to this matter remains lax, a cycle repeats: remove one harmful compound, introduce another, reassure the public and move on.

Microplastics are an even more unsettling development. These tiny fragments come from the breakdown of plastic waste and the shedding of synthetic fabrics. They are now found in oceans, soil, tap water and the food chain. Daniel Noah Halpern at GQ has shown how the rise in global plastic production has strongly negatively correlated with average sperm counts since 1970. Meanwhile, scientists have detected microplastics in significant quantities in human blood, lungs and placental tissue. More recently, a study publicised by The Guardian showed that 100 per cent – every single test subject – had microplastics accumulated in their testes, a finding that should stop any complacency dead in its tracks.

Early laboratory studies suggest that microplastic exposure can trigger inflammation and oxidative stress, potentially damaging cells and altering hormone production. Lower fertility, lower testosterone. For the ordinary person, this means that every time one drinks from certain plastic bottles, microwaves food in plastic containers or wears synthetic clothing, these artificial materials – which humanity survived perfectly well without a century ago – leach microscopic particles that invade the body through the mouth, stomach, gut and skin.

“Plastic never goes away — it just breaks down into finer and finer particles,” said one disease physician at Harvard. Some reports claim that certain populations, such as those in America, particularly people with fish-heavy diets, may be ingesting a credit card’s weight of microplastics every week (though this has been disputed in other studies as not being widely applicable).

The shift from glass and paper packaging to plastics deserves far more scrutiny than it receives. Glass jars and paper wrapping were heavier and less convenient, but they did not leach synthetic hormone-mimicking compounds into food at anything like the same scale. And glass was reusable; paper was biodegradable. Plastics transformed global commerce by reducing costs and increasing shelf life, but they were also conveniently industrial waste products from the oil industry, looking to offload their excess. Their biological safety was rarely tested thoroughly before mass adoption. The result is a vast, uncontrolled experiment on human physiology. Now that the evidence is emerging, are authorities looking the other way?

Processed foods compound the problem. Many contain additives designed to improve texture, colour and shelf life artificially, and they are often packaged or manufactured using plastic equipment that sheds chemical residues. Ultra-processed diets have been associated with higher levels of phthalates in the body. Seed oils, widely used in processed foods because they are cheap, remain controversial. These oils – soybean, rapeseed, sunflower, vegetable and the like – are high in linoleic acid, an omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid.

Mainstream nutrition often deems them safe in moderation, but excessive intake promotes chronic inflammation and oxidative stress, both of which play a part in declining fertility. High omega-6 to omega-3 ratios are linked to male infertility, with studies showing infertile men have elevated ratios in blood and spermatozoa, correlating negatively with sperm count, motility and morphology. Animal research adds to this and indicates that diets rich in sunflower oil reduce sperm concentration, while some plant-derived oils show oestrogenic effects, potentially contributing to ovarian atrophy, congestion and cysts in experimental models.

Ultra-processed foods heavy in these oils – in Britain and the United States they are found in virtually everything that is not pure fruit, vegetables or meat – amplify metabolic stress, worsening hormonal health and fertility. Regardless of one’s view on seed oils, there is no serious debate that highly processed diets correlate with obesity and metabolic disease. The average consumer is not only eating more processed food than previous generations, but ingesting a cocktail of synthetic compounds alongside it.

Another rarely discussed source of endocrine disruption is the presence of synthetic hormones in water supplies. The contraceptive pill – the use of which the Church rightly opposes on other grounds – and hormone therapies release oestrogenic compounds that pass through wastewater treatment largely unchanged. These compounds have been detected in rivers and municipal water sources. Fish exposed to such water have been feminised, and those that were not have shown reduced fertility, a clear demonstration that biologically active hormones persist in the environment.

Human exposure levels are lower and research continues, but the mere presence of hormone-active substances in drinking water raises legitimate questions. It is not unreasonable for ordinary families to ask whether their tap water contains chemicals capable of interfering with development or fertility, and why authorities have been silent. Is it ignorance, or something more troubling?

Clothing is not spared from this nightmare of modern industrial pollution. Polyester and other synthetic fabrics shed microscopic fibres during washing and wear. These fibres contribute significantly to microplastic pollution and can carry chemical dyes and treatments. One study found that among dogs forced to wear polyester underwear for a year, half were chemically castrated. Only a quarter were able to recover any reproductive capacity. The fast-fashion industry’s shift towards cheap synthetic textiles has flooded the environment with materials whose fibres can be absorbed through human skin. Cotton, linen and wool are comparatively safe. Which begs the question: why not stick to them? Wool is so abundant and cheap that it is often not even profitable for farmers to sell it.

None of this means that every plastic container or synthetic garment will make someone ill tomorrow. Not everything that harms us causes immediate death. The danger lies in cumulative exposure: small doses from thousands of sources over decades, beginning even before birth. Scientists studying reproductive decline describe foetal development as a critical window. Hormonal disruptions during pregnancy can permanently alter how a child’s reproductive system develops. Other changes may not become obvious until adulthood, when fertility problems emerge. Some research suggests that chemical exposure can even affect gene expression across generations, meaning that today’s industrial habits could influence the health of our grandchildren.

For the layman wondering what practical difference this makes, the answer is direct. It affects the food we eat, the water we drink, the containers we use, the clothes we wear and the health of our children. It affects whether sons struggle with fertility decades from now or whether daughters experience hormonal disorders at increasingly young ages. It affects healthcare costs, demographic stability and the future viability of ordinary family life. These are real issues with concrete human costs playing out in hospitals, fertility clinics and classrooms today.

Regulatory responses have been slow and fragmented. The European Union has restricted certain chemicals, including some uses of BPA, yet thousands of industrial compounds remain insufficiently tested. Corporate lobbying has historically delayed regulation and even obscured truth, as happened with sugar, tobacco, and asbestos. The ordinary consumer is left navigating supermarket aisles filled with products whose long-term health effects remain uncertain.

Industrial civilisation has always produced unintended consequences. Leaded petrol once seemed a miracle; asbestos was once celebrated as a fireproof marvel. Only later did societies recognise the devastating health costs. The current chemical era may represent a similar turning point. If declining fertility, hormonal disorders and chronic disease continue to rise alongside widespread chemical exposure, future generations may look back on this period with astonishment that the warnings were ignored.

In the spirit of discerning truth from error, Catholics must confront this reality without the intellectual laziness that accepts corporate or bureaucratic assurances at face value. Just as we reject clerical overreach when it misrepresents Tradition, we must scrutinise an environmentalism that fixates on distant and contested climate projections while ignoring the immediate and documented chemical pollution of our bodies and those of our children. The Church teaches that man is steward of creation, not its exploiter for short-term gain. When industrial practices poison the wells of life itself, fidelity demands that we call it what it is: a grave moral failing.

Gavin Ashenden once argued in the Catholic Herald that man needs saving before the environment, and that abuse of the environment is downstream from human sinfulness. This is true: the Church’s primary enemy is sin. But the body and nature play into this picture. A man saturated with narcotic or stimulant chemicals will have altered behaviour, just as a drunk man may be more violent or profane. Nature and supernature work best in harmony. What affects our bodies affects our decisions, and our decisions affect our relationship with God and our salvation. This is the Church’s remit. Industrial pollution shapes the everyday lives of the faithful, and the evidence suggests it does so adversely.

Recently I wrote against lazy Catholicism. I also interviewed Cardinal Gerhard Ludwig Müller, who warned orthodox and faithful Catholics against interpreting every word or opinion of the Pope as automatically true and infallible. In the wake of the Epstein scandal, we cannot lazily assume that governmental authorities are diligently protecting us from toxic substances in our food, drink and clothing. They are not, or not sufficiently.

It is only right to ask why. Colloquially online, this slurry of industrial poisons is sometimes referred to as “slop”. But whatever the label, it must stop. It represents a far greater and more immediate assault on mankind than anything Greta Thunberg or the World Economic Forum have decried. The Church – ever on the side of man when all else betrays him – must speak out and make its voice heard.