Samantha Smith is a journalist whose work appears in The Spectator, The Daily Telegraph, and The Daily Mail, and she is a regular commentator on GB News. Despite being in the middle of completing a law degree at Durham University, she has already emerged as one of the leading conservative voices in Britain and one of its most promising young writers. Her success comes in spite of a past marked by severe abuse and institutional neglect. She was made homeless as a teenager and was groomed and sexually abused from the age of five to 14. She grew up in Telford, where the abuse of children was routinely ignored by police and local authorities in order to avoid stoking racial tensions.

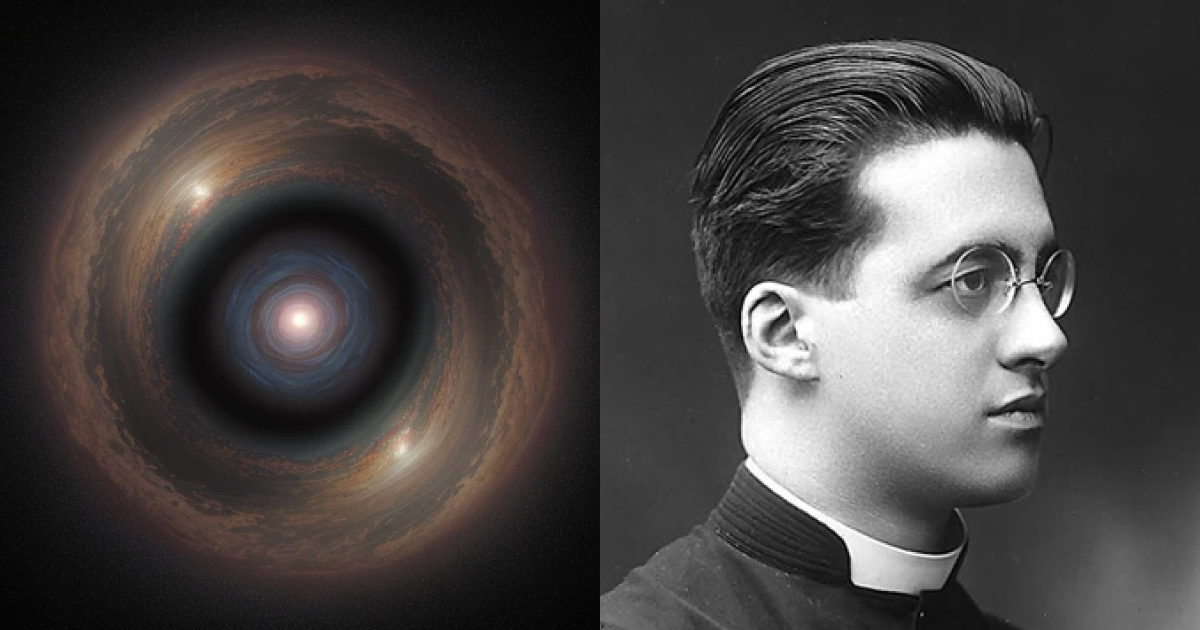

Samantha's experience is one of being systematically failed by the very institutions tasked with protecting children. Since being taken on by The Spectator in 2020, Samantha has used her platform to expose the scale of the grooming gang scandal and the culture of denial that surrounded it. Her writing has helped force the issue into the mainstream and bring attention to victims who are too often ignored. With child sexual abuse at the forefront of national debate, The Herald sat down with Samantha to hear her story, discuss the institutions and attitudes that allowed child sexual abuse to go unpunished, and explore how her Catholic faith has shaped her response.

Could you tell us how you came to be a leading voice fighting for the victims of abuse in the UK?

I was abused for well over a decade, from the age of five until I was a teenager. I was abused by a series of different men at different times throughout my life. I was in children's homes and on social services from the time I was a teenager, and I was homeless at times. I did lapse from Catholicism for a short period of time, just because I didn't understand how a faith that is meant to save and protect and absolve could allow for the abuse that I experienced. But I realised that evil and sin are not a product of Christianity or God or Catholicism, but a product of the human rejection of Christian ideals and Christian values.

I often get comments about why I speak up about Pakistani Muslim grooming gangs, but not about the Catholic Church, which also had this massive abuse scandal. However, the Catholic Church dealt with—and is dealing with—the evils within our own house at a far faster and more decisive rate than general British society is dealing with Pakistani Muslim grooming gangs.

Yes, the Catholic Church has failed in many ways historically to address abuse. But the difference is that we, at the very least, are willing to confront it as an evil that exists. While the attitude towards what I experienced—and what thousands of other girls have experienced across the UK—is that they're always seeking to discredit and disprove.

Despite the prevalence of this evil in British society, which is continuing to go on, with little girls continuing to be abused, the great and the good will do everything in their power to decry its existence and discredit those who speak out as racist or xenophobic or extremist.

The things that I experienced were, yes, a product of evil men doing evil things, but more so than that, it was a product of society and the structures that were supposed to protect me failing to do so and ignoring the existence of the evil that I fell victim to. I remember being asked if I consented to sexual activity at any point. Bear in mind, my abuse started when I was five years old. A child cannot consent to sexual activity.

Why do you think there is this different approach to the abuse that happened in the Catholic Church and the grooming gang scandal?

The difference with the abuse in the Catholic Church and the grooming scandal is that the Church is still widely seen as a white institution, despite the huge growth in Africa and Asia. It is still, from a Western lens, seen as a white Western juggernaut in the religious ecosystem.

Because of this, there is not the same level of cultural sensitivity as there is in the grooming gang scandal, because with Pakistani Muslim grooming gangs, these are Muslim men perpetrating this particular type of crime.

There is always the point made that sexual predators in Britain are white men, or that most grooming gangs are white men. Yes, most criminal exploitation gangs are composed of white men because we are a majority-white nation, and that’s what makes the Pakistani grooming gang scandal so unique and so difficult to address—because it is, I say this as a brown woman, a brown issue in a white world.

So while with the Catholic Church it is white people talking about a white problem in a white institution (even though that isn't necessarily true in reality), in the grooming gang scandal it’s white people in a white nation—white politicians—talking about crimes perpetrated by a brown subsection of a Muslim faith. And so there is this sort of deference that we have to a community which is not our own.

In the Telford report and the Rotherham report, it was said in no uncertain terms that CSC [children’s social care] failed to address the problem because of analysis about race. That is the crux of the issue: white people are afraid to talk about an issue that they don't see as coming from in their own house.

There's a national complicity. I did a great panel with Allison Pearson from The Telegraph recently, and she phrased it as “girls for votes.” That is absolutely what it was in Telford and Rotherham, in Rochdale, in Banbury, and in Oldham. Across the country, girls—predominantly white working-class girls—were seen as fodder, and their abuse as a necessary evil and an inherent by-product of diversity and multiculturalism.

It is seen as a necessary evil in allowing multiculturalism and in accepting diversity and in fostering a sense of inclusion in our society that we allow alien cultures and alien approaches to women. This line again is bandied about—that all cultures are equal—but from a Catholic standpoint and from a British standpoint, that is not true. In my opinion, no culture that allows or condones the marriage of six-year-old girls to men old enough to be their grandfathers, no culture which denies women access to the workplace, the ability to speak in public, the ability to attend school or university, the ability to have a driver's licence or leave the house without male accompaniment—no culture that has those beliefs is equal to ours or should be respected as such.

What do you think would actually have a significant impact in eradicating this evil?

It is still in its infancy, but I have started—and I am now one of the directors of—a limited liability company called Action for Accountability. We are working with a team of barristers and lawyers to identify key institutions and individuals who were the architects of creating the scenarios where this abuse was allowed to carry on. Not the perpetrators themselves, but the councillors, politicians, police and crime commissioners, social services workers.

Anyone who's in a position of authority whose duty it was to identify, support, and prevent the abuse of little girls who failed to do so—and are continuing to fail in their basic duties—we are looking to privately prosecute.

We are not going through the Crown Prosecution Service, because we've seen with rape and sexual abuse cases that 98.6 per cent of rape cases never make it to court, and an even lower percentage of child sexual exploitation and grooming cases are prosecuted.

Whilst those who fail to protect little girls are the same ones who are expected to implement the recommendations of inquiries and exposes and reports, nothing is going to change. If the perpetrators and the cover-up artists are marking their own homework on their failure in this scandal, then we can't expect any real meaningful change to be brought about, and no individual in a position of authority has ever faced consequences for their inaction.

That is what is going to have the most meaningful and immediate impact, because as soon as you see a politician, an MP, a council leader or a senior police officer being taken to court for their failings, others in a similar position who may have repeated those failings across different areas will look at that and think: “Oh, perhaps I'm not as infallible as I have been led to believe thus far.”

Over the past years, Labour has seen the white working class desert them, increasingly voting for other options. Do you think the grooming gang scandal is connected to this?

Labour's entire thesis for its creation—back when it was only the Liberal Party and the Conservatives—was “of the people, for the people.” They were seen as the antithesis of metropolitan elitism, and yet now they themselves are so ingrained in the system, they have become a part of the problem.

They are still trying to act and retain this image of being for the working class, but it is fundamentally incompatible with the fact that it is Labour councils and Labour-led areas and Labour politicians who have turned a blind eye to—and covered up—the systematic abuse, sexualisation, rape and murder of little white working-class girls in their areas. They can't cling on to this ideological image when the reality is laid bare in stark contrast.

For the Tories, conservative ideals and values come naturally to their politics. There isn't the same tolerance for anti-British cultures. For Labour, a big part of their voting base and their foundation has been built on encouraging multiculturalism and encouraging the very same structures that have led to the failure of working-class girls.

It is quite controversial to say that, but I have always thought that I'm able to say a lot of the things that I do because I am a mixed-race woman with a brown family. Jess Phillips, Keir Starmer, Angela Rayner and Yvette Cooper are not. They engage with a huge amount of pandering and deference to the Muslim community and to ethnic minority communities in general because there is this idea that other cultures are the experts on their own culture. That is logical, but that doesn't mean that British society has to defer to them on issues relating to justice or moral standards.

In the UK we are seeing an increase in Church attendance, particularly amongst young men and particularly in the Catholic Church. Why do you think that is?

I think that men—and white men in particular—have been stripped of their agency and identity for so many generations in a row. They are constantly told that there is no place for them in a modern progressive society, and that white men are the enemy. The hardest thing to be in modern Britain is a white working-class boy, because they have no agency. Anything that they hold dear, or have been taught to value or love or be proud of, is now something that they should carry with them as a burden of shame. Whether it's their love of football, or going into a trade, or whether it is traditional English values, whether it's the military—anything that traditionally white men have populated is mocked.

I think that young men are going to the Church, and particularly the Catholic Church, as a way to reclaim identity and agency. In every part of British society, white men have been muscled out, and young men of my generation are seeking some sort of identity, some sense of belonging, some agency—some way to feel as though they are accepted in British society. That is why they are turning to Catholicism.

On the other hand, the Anglican Church was built upon a foundation of changeability and social reform. You can't look at the Church of England and its foundations as anything but the product of changing social ideals and changing ideology.

While the Anglican Church exists as an institution that is changeable and fallible and subject to external influences, I think of the Catholic Church as its own Eden. The Catholic Church has become a spiritual home for many because it is the only institution in the Western world that is not influenced or affected by social ideals. There are parts of the Catholic Church that do not realise that is its unique selling point. There is this false narrative that to survive one must adapt and change, whereas the very thing that has ensured the survival of the Catholic Church and its permanence in modern society is its lack of changeability—and that it has not altered in the centuries of its existence.

.jpg)