The Fourth Sunday of Advent invites us to inhabit a place where we learn to practise a greater degree of trust. This deepens with each cycle of the liturgical year as annually we make this preparation for the feast of the Incarnation.

The reading from the Old Testament takes us to the prophet Isaiah, who places before us a perennial dilemma that never goes away. In the face of a crisis, do we try to fight our way out using the resources of pragmatism and the politics of power and persistence, or do we explore the promises of God and learn to exercise courage and faithfulness in the spiritual dimension?

As king of Judah, Ahaz faced perennial threats in Middle Eastern politics. He was surrounded by an alliance of nations that wished him harm, and in the middle of this crisis he turned to the prophet and asked for help. The prophet told him he could trust in God to deliver him and his kingdom, and that God would in fact give him a sign.

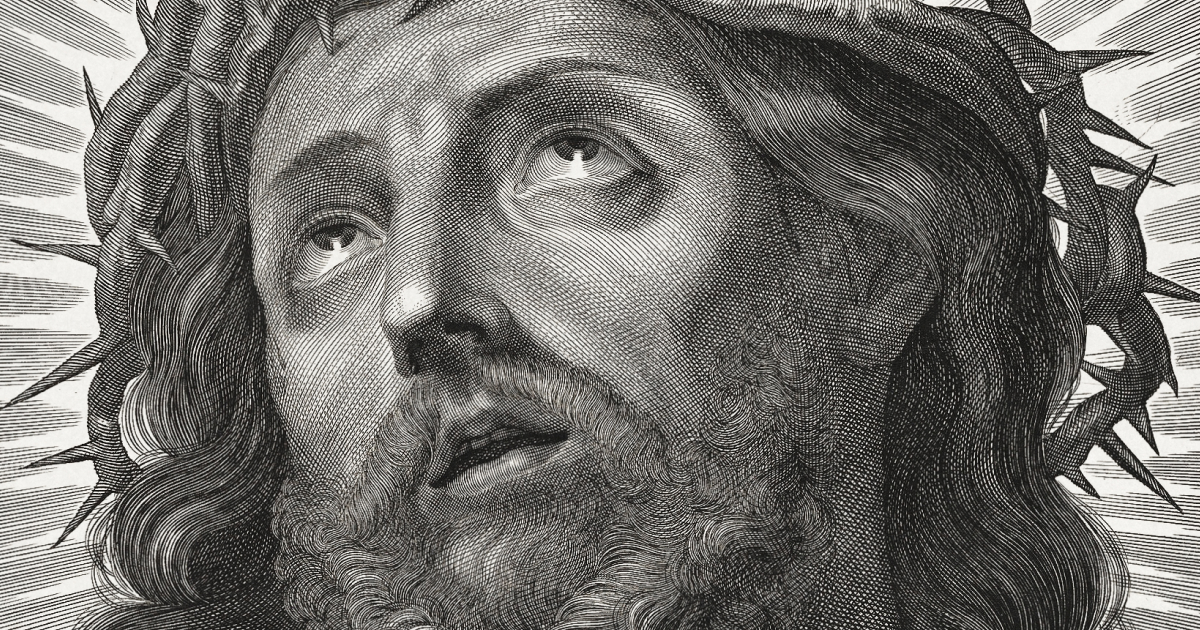

Isaiah told Ahaz that a young woman would conceive and bear a son, and his name would be Emmanuel.

We do not have any records of the infant born under Ahaz, of who his parents were, or how he was named. But we do know that this crisis in the 7th century embedded a prophecy in the wisdom and consciousness of Israel: that God would intervene on some greater scale, with a mother and a child named Emmanuel.

The prophecy, however, was wasted on Ahaz. He replied with the impatient petulance of a man who wanted a solution, not a prophecy.

Ahaz, of course, is not just a 7th-century king of Judah. He represents more than that. He stands for each one of us. Each of us faces the question of whether, confronted with the many crises that threaten us, we orientate ourselves in prayer and trust towards God, or whether we try to fix the disunity, disorder and dangers on our own terms, using our own resources.

The Epistle for the Fourth Sunday of Advent takes us to the opening lines of one of the most astonishing and revolutionary letters Paul wrote to the Church.

As a prelude to what he is setting out to do, Paul explains that the whole purpose of his writing is to help us grow into our calling to be saints: to distinguish between the world of the flesh and the world of the Spirit; between the world of self-sufficiency and the Kingdom of Heaven.

He traces his calling – and ours – to the Resurrection. It is the Resurrection that provides a dynamic power to move us from one place of perception to another: from the world of our own limitations to the limitless potentiality of the Kingdom of Heaven.

The Gospel for this Sunday is framed by Saint Matthew rather than by Saint Luke. Each writes an infancy narrative, but with a different purpose. Saint Luke tells us the story from Mary’s perspective, giving us the narrative of overwhelming events from the point of view of the Mother of God, who stood at the centre of time and history.

Saint Matthew, by contrast, is the evangelist to the Jewish Christian community, and he frames his narrative in terms of the Jewish legitimacy of the line of David. He uses the guardianship of Joseph, descended from David, to root the Incarnation into the structural coherence of the Jewish historical narrative. He reads the event through the eyes of the man given pragmatic responsibility for the protection of the Mother of God and the Christ.

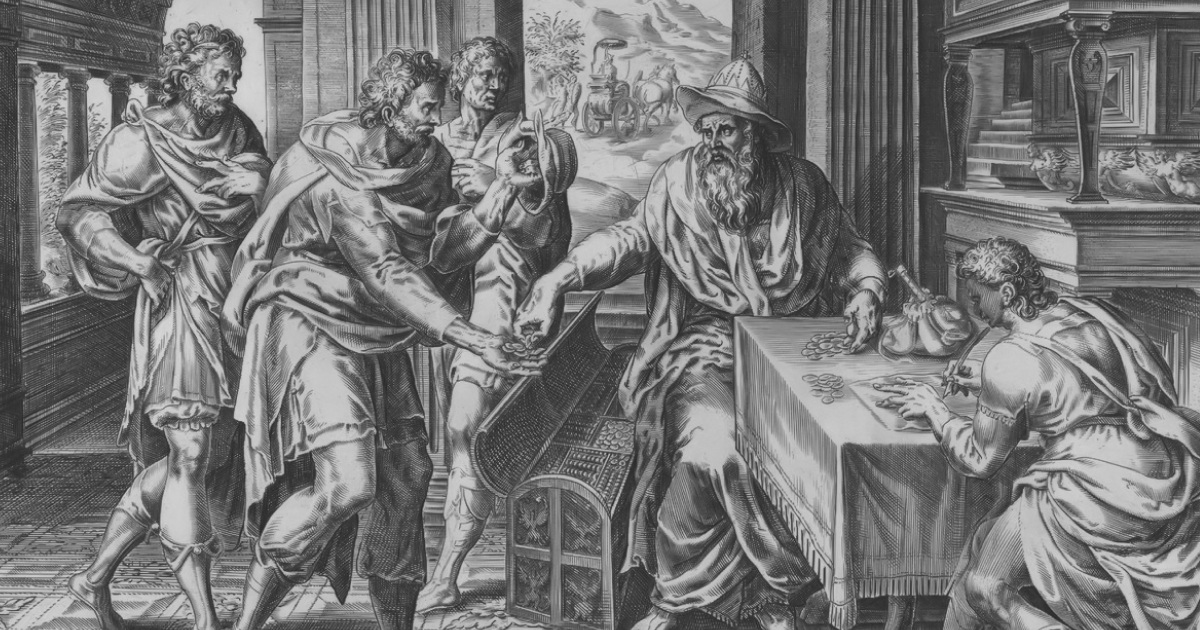

Saint Matthew invites us into the arena of shame into which Joseph was unwillingly drawn by the invitation to trust what he had been told about Mary – only to apparently discover, as he had feared, that the wool had been pulled over his eyes. He had been tricked. The girl to whom he had been betrothed on the basis of her purity and his need to offer protection was, it seemed, the worst and not the best kind of young woman.

So he set out to wash his hands of the situation, to ensure his own moral safety, and to distance himself as swiftly and as hygienically as he could.

God, however, invaded his sleep with an angel. And the integrity of Joseph’s relationship with the living God was sufficiently deeply rooted to allow him to trust the authenticity of his dream, and to risk everything on the promise of that encounter and the command of his Creator.

The dilemma that Joseph faced reminds us that faith never comes without risk. Each of us has to agree to an obedience that costs us more than our public reputation and our private pride. Each of us, like Joseph, faces an invitation to exercise responsibility for God’s purposes by being willing to sacrifice other, more immediate and more attractive options.

The vocation of Joseph had little glamour to it, but a great deal of responsibility. What was asked of him was a masculine trust: responsibility, courage and determination, through which God could accomplish his purposes – not just for Joseph’s family, or for the nation of the Jews, but for all people and for the whole of creation.

The Fourth Sunday of Advent invites us to reflect on the way in which God uses the trust of his disciples and on how no moment of uncertainty, no place of darkness, no apprehension of threat has the power to withstand his promise and his protection.