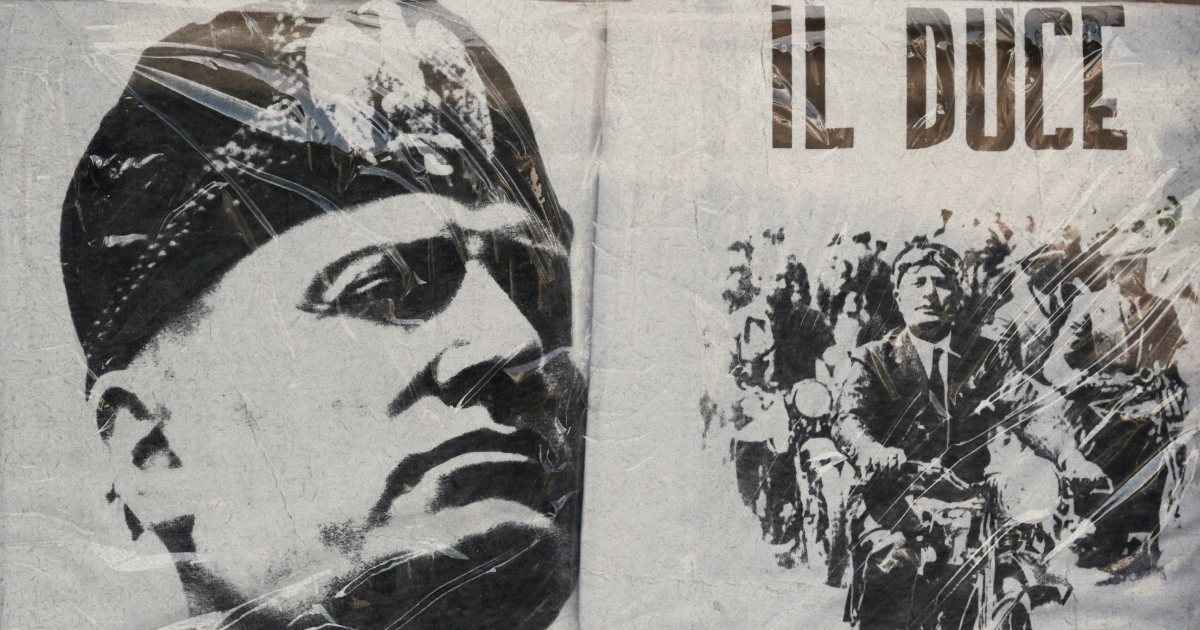

Eighty years ago this year, on 29 April 1945, the body of Benito Mussolini was hung upside down in Piazzale Loreto, Milan. Having been shot dead the day before by Italian partisans near Lake Como, he would not have been alert to his surroundings. But had he been, he would have heard the bells of the Chiesa del Santissimo Redentore in Milan, the Church of the Most Holy Redeemer, ringing out just a few hundred metres from the square, calling the residents of the city to Holy Mass.

Given the option, whether Mussolini would have attended church that day is difficult to know for certain. The Nazi controlled north of Italy had fallen, with the Allied controlled south victorious. Perhaps the former dictator would have finally felt inclined to repent for a rule that plunged Italy into civil war, or perhaps to offer prayers of thanksgiving that he was still alive to tell the tale despite being on the losing side. In any case, no such option was afforded to him. He did not receive a Church funeral, instead being buried in an unmarked grave in Milan’s Musocco cemetery.

Had he gone to Mass, it would have marked a bizarre break with the pattern of his life, having never been a Mass attender. The dictator, who died as a Nazi dependent, lived in a manner that was often marked by hostility to the Catholic Church.

Born to a practising Catholic mother and a devoutly atheist father, the young Benito followed, as many children do, the beliefs of his father. He rejected the spirituality of the Salesian run boarding school he attended, and a fierce anti clerical streak ran through his life as a young man. He was violently opposed to the influence of religion on Italian society and viewed Catholicism as a form of subservient cowardice.

As a young man, Mussolini made blasphemous comments about the Eucharist and disavowed the historical Jesus as “ignorant”. He wrote for the socialist newspaper Avanti!, becoming its editor in 1912 and using it as an outlet to peddle anti Catholic propaganda. Dismissed from the role in 1914 for supporting Italian intervention in the First World War, he embarked on an ideological journey that led him to Fascism before the end of the decade.

Through a mixture of intimidation, violence, and persistence, Mussolini found himself asked by King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy to become prime minister. By 1925, Italy had become a one party Fascist state.

The Church had not fared well since Italian unification in 1861 and in 1870, the Kingdom of Italy seized Rome from the Papacy and brought an end to the Papal States. What followed was a series of liberal parliamentary coalitions that were antagonistic to the faith. The government restricted Church involvement in society, encouraged civil marriage and secular education, and was widely perceived as a hostile force towards the cradle of Christianity.

Wary of Mussolini’s Blackshirts, but also conscious of the existential threat posed by the anti Catholic Italian Socialist Party and the hostility of the liberal political order, the Church maintained a cautious neutrality during the Fascist takeover and while in power, Mussolini’s relationship with the Church was marked by uneasy coexistence. Exhausted by decades of political marginalisation, the Church welcomed the reintroduction of religious education in public schools, the return of religious symbols to public life, and a renewed emphasis on Italy’s Catholic identity. This tentative amiability reached its height with the Lateran Pacts of 1929.

The Lateran Pacts resolved the so-called Roman Question, a political dilemma that had dominated Church–state relations since 1870. Italian unification had placed the pope’s spiritual authority under the sovereignty of the Italian state, a situation Pius IX considered entirely unacceptable. The Church insisted that its centre required independence from all political power. The treaty recognised Vatican City as an independent sovereign state, required the Italian government to pay compensation for the seizure of the Papal States, and made Catholicism the state religion of Italy.

The relationship, however, soon deteriorated. Mussolini sought a Church subordinated to the Fascist state and easily manipulated. He took particular issue with Catholic Action, a lay Catholic movement promoted by the Church to organise the faithful for religious, educational, and social apostolate under episcopal authority. Directly answerable to the bishops, the movement had, by the early 1930s, as many as two million members, dwarfing Mussolini’s Blackshirts, whose numbers remained under one million. In 1931, Mussolini moved against Catholic Action, accusing it of political activity and ordering the closure of its youth clubs and meeting halls.

Pius XI, midway through his sixteen year pontificate, responded decisively. On 29 June 1931, he issued the encyclical Non abbiamo bisogno, condemning Fascist attempts to monopolise youth education, denouncing the pagan worship of the state, and asserting the Church’s right to organise the faithful independently of political power. The pope’s intervention forced Mussolini to retreat and allowed Catholic Action to resume its work, though state surveillance continued.

In 1932, during an audience with Pius XI marking the anniversary of the Lateran settlement, Mussolini appeared to gesture towards reconciliation. As a young socialist agitator, he had once publicly dared God to strike him dead. During the audience he declared: “Today I no longer deny God by according him five minutes in which to strike me dead as proof that he exists. I now know why I was not struck by lightning: the Church needed me.”

But a further rupture followed in 1938, when Mussolini introduced racial laws modelled on those of Nazi Germany. Pius XI condemned racism and antisemitism in speeches and addresses, criticising doctrines that placed race or nation above God.

Even amid these tensions with the Church, Mussolini’s understanding of religion shaped his political worldview, particularly in foreign affairs. In the early 1930s, his hostility towards National Socialism, which he viewed not merely as a rival authoritarian movement but as a threat to Catholic civilisation, came to the fore over neighbouring Austria. Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss’s Austrofascist government, corporatist and explicitly Catholic, was regarded in Rome as a natural ally and as a necessary barrier against German expansion.

Austria’s Catholic identity mattered greatly to Mussolini, who saw Anschluss as the destruction of a Christian political order in favour of what he perceived as a racially pagan and ideologically radical German Reich. When Dollfuss was assassinated by Austrian Nazis in July 1934, Mussolini reacted with fury, ordering Italian troops to the Brenner Pass and signalling his readiness to go to war in defence of Austrian independence. G. K. Chesterton remarked that with Dollfuss’s death “the last remains of the Holy Roman Empire” had perished.

Domestically, the strained relationship endured until Mussolini’s death in 1945. In his final days, he sought the counsel of the Bavarian Cardinal Ildefonso Schuster, later Blessed Ildefonso Schuster. On 25 April 1945, the cardinal urged him to make peace with God and with men. Mussolini refused. He was killed three days later.

Thus ended the life not only of a man, but of a political leader who, like many others, did not have an entirely straightforward relationship with religion.

After his death, Italy underwent profound transformation. The collapse of Fascism, followed by the fall of the Monarchy, paved the way for the establishment of the Italian Republic in 1946. As Italian institutions sought to distance themselves from their past, some within the Church offered a strikingly different perspective. The Sardinian mystic Blessed Edvige Carboni is reported to have said that Mussolini, after a period of purification in Purgatory, had ultimately been admitted to Heaven, declaring in 1951: “This morning the soul of Benito Mussolini has entered into Heaven.”

Whilst Carboni’s words are far from dogma, and the Church holds no position on the salvation of individuals beyond the canonised saints, Mussolini’s complicated relationship with Catholicism is not beyond redemption, even if it was far from innocent.