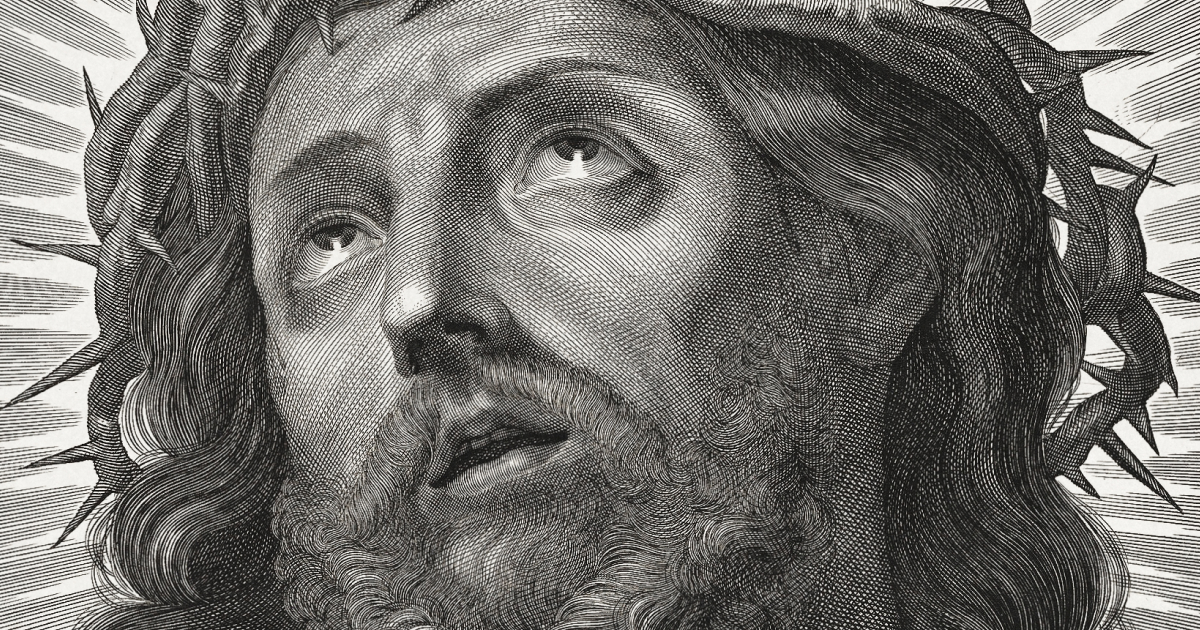

This year marks the 1,700th anniversary of the Nicene Creed. Week by week we recite: “He believes in Jesus Christ… who by the Holy Spirit was incarnate of the Virgin Mary, and became man.” Familiar words — but astonishing ones. That single clause bears a young woman’s voice, her agency, and a revolution sung into the world.

Tradition places Mary at perhaps fifteen: poor, Jewish, living under Roman occupation, unmarried and about to be pregnant in a culture where shame could kill. Into that world comes an angel and a call she cannot fully comprehend. Mary’s response is freely given: “Behold, the handmaid of the Lord: be it done unto me according to thy word.” We too easily hear this as passive submission. It is not. It is the first courageous fiat in Christian history — an act of consent, not capitulation. God does not impose; God invites. Salvation began not with conquest but with a conversation, and depended on the consent of one teenager.

Mary’s fiat was not a single moment; it was a life. It began at the Annunciation and continued through hidden years of ordinary faithfulness: at Cana, where she quietly nudged reluctant power into generous action; and most shatteringly, at the Cross. When many of the men fled, the women remained. Mary remained. If the Annunciation is the first yes of Christian faith, Calvary is Mary’s last and greatest — consent as endurance, as presence, as love that refuses to walk away. That is not meekness. That is moral strength.

Between angel and Cross, Mary sings. The Magnificat is not a lullaby; it is resistance poetry: “He has scattered the proud… brought down the powerful from their thrones… lifted up the lowly… filled the hungry with good things.” This is not private sentiment but public proclamation, spoken by a young woman whose very body becomes the place of God’s solidarity with the vulnerable.

For centuries the Church has often presented Mary chiefly as an emblem of purity and silence. The Gospels give us someone else: a woman who thinks and speaks, questions and commits, decides and directs. She is there at the birth of Christ and there again at the birth of the Church, gathered in prayer at Pentecost when courage comes to fearful men. If the Creed proclaims that divine life takes flesh in a woman, the narratives show her announcing divine reversal before Jesus preaches the Sermon on the Mount. In that sense, she is the first theologian of the New Testament, the prophet whose song sets the key for her Son’s ministry. The Incarnation is God taking sides — with the lowly — and asking a woman to voice it.

The Magnificat does not romanticise poverty; it promises reversal. It does not deny power; it redeems it — by bringing the high low and lifting the low high. If that embarrasses us, the problem is not with Mary. The problem is our preference for a faith that blesses the status quo.

There is tenderness here too. A feminist reading of Mary does not harden her into ideology. It honours her courage without denying her vulnerability. The risk she faced was real; the cost she bore was immense. Consent, in this story, is not a form to sign — it is a life laid open. Many women recognise themselves in Mary: not because they are asked to be quiet, but because they have learned to be brave; not because they carry burdens alone, but because they know the power of standing by those they love when others walk away.

And this has consequences for the Church. If the Creed centres Mary’s fiat, then our discipleship should centre consent, conscience and the dignity of the lowly. We should measure authority not by volume or status, but by the courage to serve. We should teach boys and girls alike that strength is not domination but fidelity; that keeping company with the suffering is the holiest power we know.

“Incarnate of the Virgin Mary” is a theological truth with ethical demands. It asks the Church to prize consent, to seek justice, to lift the lowly, to protect the vulnerable and to let Mary’s song tune our own. The most revolutionary words ever spoken were whispered by a teenage girl: “Be it done to me according to your word.” And perhaps the deeper revolution was not that God became human, but that God chose to begin by empowering a young woman — and then kept company with women who did not run.

If we listen again to Mary’s song, we may yet find our own courage: not only to speak of justice, but to stand beside it, to stay with it, and to keep saying yes.