The fame of American Catholic poet Phyllis McGinley — a traditionalist homebody among avant-garde contemporaries — has faded under criticism from modernists. Yet McGinley, of Irish descent, cared little for her reputation after a lifetime balancing financial need with Catholic conviction.

Unlike many witty, though bitter, writers of buoyant verse, she was essentially an optimist on account of her religious convictions. She assured Time magazine in 1954 that the 20th century would provide a bumper crop of saints: “Saints always crop up in times of trouble and crisis and heresy, and this is a period of the greatest heresy the world has ever known.”

A typical meditation was on St Jerome, whom McGinley dubbed “The Thunderer” and “God’s angry man” as well as “the great name-caller”. She summed up the ascetic Jerome as:

“A born reformer, cross and gifted./ He scolded mankind/ Sterner than Swift did.”

While offering musings about leading lights of the Roman calendar, McGinley also celebrated some less remembered stalwarts, such as Madeleine Sophie Barat, RSCJ, who founded the Society of the Sacred Heart, or St Francis Borgia, who was, she noted, “Born both Borgia and God-struck Man.”

With a wry, even chaffing tone, she probed biographical anecdotes of the saints, such as the charity of Martin of Tours, who used his sword to cut his cloak in two, to give half to a beggar clad only in rags in wintertime. Struck by this odd benefaction, McGinley decided:

“Half-way warm/ Is better than freezing/ As half a love/ Is better than none.”

She also highlighted those she deemed “unordained saints” for their ardour and achievements: Florence Nightingale, Mahatma Gandhi, and John Wesley. In her book Saint-Watching (1969), McGinley noted that saints were “geniuses who brought to their works of virtue all the splendour, eccentricity, effort, and dedication that lesser talents bring to music or poetry or painting.”

Dismissed as a light versifier by more sombre US poets like Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton, McGinley was defended by Mary Stack McNiff, assistant to the librarian at St John’s Seminary, Boston. McNiff argued that while McGinley could be funny, “what is even better, she can be both serious and spiritual — and with a light touch.” This impression of ease was the product of what McGinley described as “cruel” labours, requiring sustained effort and application.

Her reward, apart from honours from Catholic organisations, was the spiritual company of Philip Neri, considered by her as “the merriest man alive”. Prolific in prose as well as verse, especially after an unexpected Pulitzer Prize abashed her into silence as a poet, McGinley shared her opinions on beatification issues.

Decades after St Frances Xavier Cabrini MSC’s canonisation, McGinley resented Rome’s failure to canonise a “truly native [American] candidate”. In 1969, she proposed Katharine Drexel, a Philadelphia heiress and founder of the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament, who combined “holiness with indigenous Yankee know-how … as unmistakably American as Catherine of Siena, say, was Italian.” She likewise revered Dorothy Day.

Equally forward-looking about literature, in 1957 McGinley praised the religious poetry of Daniel Berrigan SJ as unsentimental: “All is sinewy, strong, astringent. If anything, it is too lean for casual enjoyment.”

That same year, she lauded Mary McCarthy’s Memories of a Catholic Girlhood for having “come as near the truth as is rationally probable”. She also corresponded with Sister Mary Madeleva, president of Saint Mary’s College, Indiana, known as the “lady abbess of nun poets”, who wrote in defence of Geoffrey Chaucer’s Prioress from The Canterbury Tales.

Despite her reputation for wit, McGinley’s seriousness might be seen in her essay composition technique; she often prepared a po-faced version before inserting humorous glints as an afterthought.

The ever-abiding morality inherent in her reflections is seen in the suggestion that she may have inspired the philosopher Hannah Arendt to refer to the “banality of evil” when reporting on the trial of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann. In a 1961 article in The Ladies’ Home Journal, McGinley had opined about fiction: “To overstress evil is as banal as to overemphasise goodness.” According to her, authors who err in either respect find their works irrevocably dated.

On moral issues, her views could be quirkily individual. In 1968, New York governor Nelson Rockefeller chose her to serve on a committee to review the state abortion law. McGinley participated in hearings and filed a report recommending that each woman be permitted her own choice in the matter rather than abiding by state-level intervention.

For all her self-identification as a “housewife poet”, a 1965 Time magazine profile revealed that McGinley was a quasi-martyr to her own domestic obsessions, tormented by a spinal injury after falling on a freshly waxed kitchen floor. Different pains were implicit in the discipline needed to write, which she saw as “cruelly difficult”.

She would regale her family with a full hour of reading aloud nightly, sometimes of her newly written works, or silently in the family circle. She was introduced to her husband after meeting his sister at the St Francis health resort in New Jersey, run by the Sisters of the Sorrowful Mother.

A hectic early upbringing made the Oregon-born McGinley relish hearth and home, and the suburban lifestyle she favoured necessitated constant productivity, to the point where her husband retired to manage her complex professional career. She was regarded as the poet of suburban life, though she also diversified into children’s stories.

Financial obligations may have motivated one of McGinley’s only public missteps, when she allowed her name to be used in a notorious scam exposed by Jessica Mitford in 1970 in The Atlantic. The Famous Writers School, founded by publisher Bennett Cerf, duped American semi-literates into thinking they could win fame as professional writers by paying exorbitant correspondence-course fees. Flippantly replying when Mitford ventured a sum that figureheads supposedly received, McGinley quipped: “Well, I may have a price on my soul, but it’s not that low; we get a lot more than that!”

Although she routinely refused to read from or discuss her work in public (another possible reason for her decline in celebrity in an electronic age when recordings of even obscure poets are available online), McGinley was typically omitted from sober-sided general anthologies and collections of women’s writing — the latter because of her vocal anti-feminism, or at least what she saw as feminism.

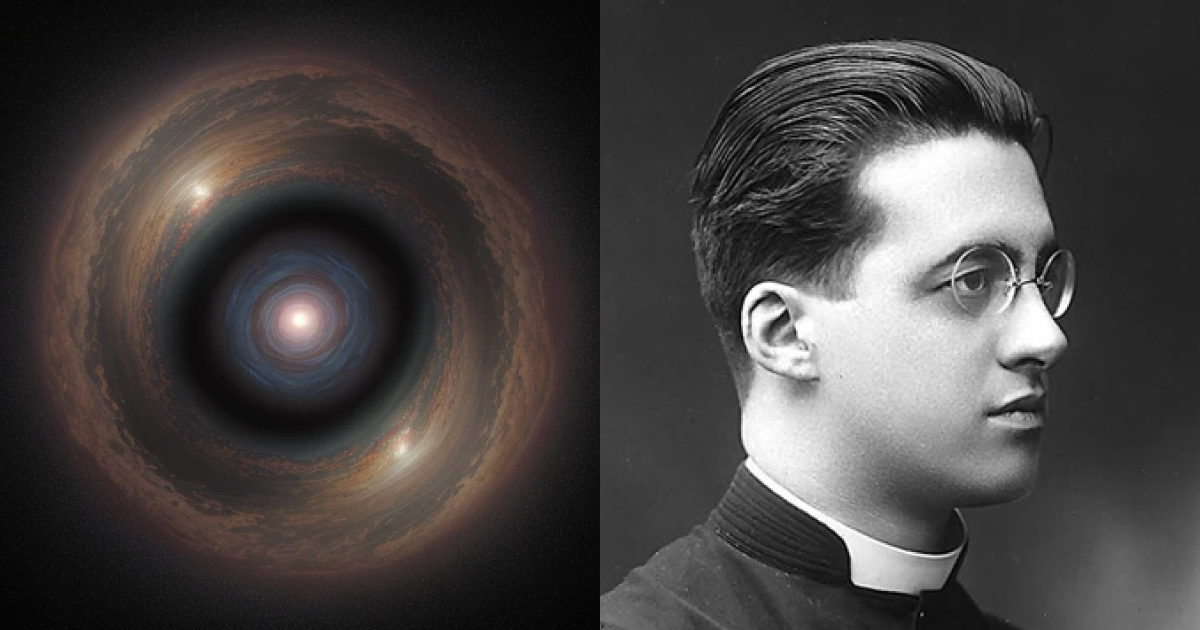

An aura of mystery surrounded her, despite the omnipresence of her work in best-selling magazines. So it was a tribute to her remoteness as well as intellectual acumen when reportage of the Second Vatican Council in The New Yorker, signed with the pen name Xavier Rynne, was once ascribed to McGinley. The real author was Francis X. Murphy, a Redemptorist priest.

Likewise, McGinley was cited by cognoscenti, as when Father Edward J. Romagosa SJ introduced the Catholic writer Flannery O’Connor in 1962 at a literary event. Father Romagosa mentioned a poem by McGinley warning children that learning the ABCs might one day lead to authorship and eventual presence at literary dinners.

McGinley, fond of her domestic comforts — as was Chaucer’s Prioress — merits rereading today.

.jpg)