The best Christmas films are in some way spiritually uplifting and my first choice is no exception. It’s a Wonderful Life, made in 1946 but not well known until the 1970s due to a quirk of copyright, stars James Stewart as George Bailey, a struggling local banker in the fictional township of Bedford Falls who, following in his father's footsteps, tries to help his customers rather than extort them, unlike his arch-rival in the town, Mr Potter.

As a boy and young man, George longs to escape from his roots and travel the world, but his self-sacrificing nature – taking over the bank after his father's unexpected death and allowing his pilot brother to follow his career elsewhere – means that he stays put. He marries the charming Mary (Donna Reed) and raises a family.

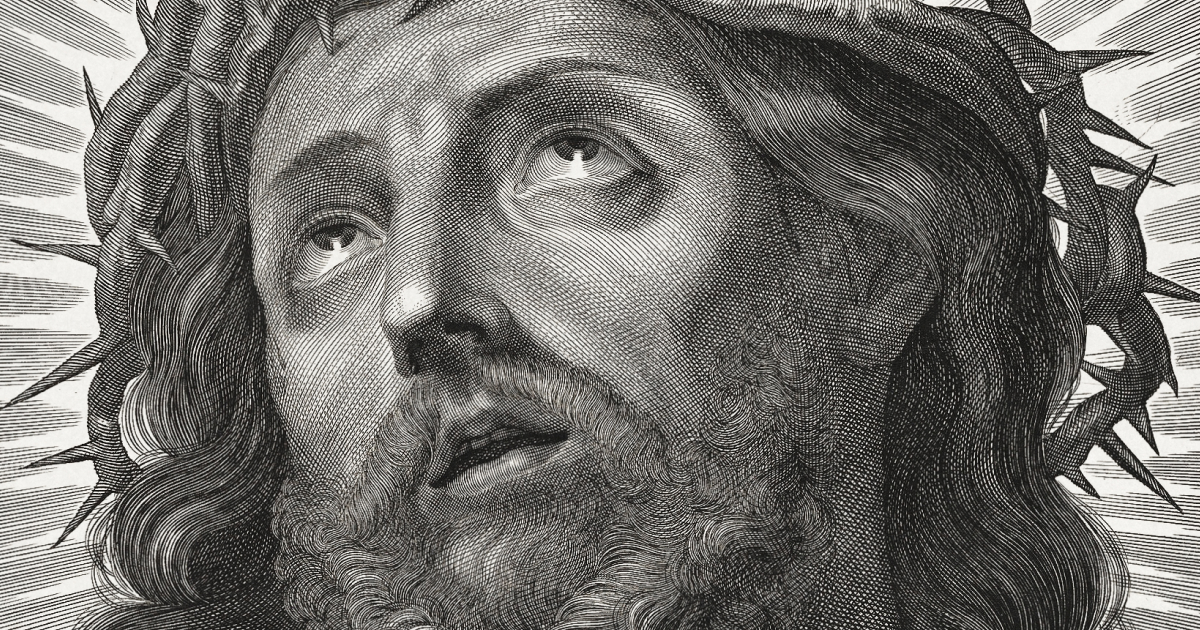

When a huge amount of money goes missing in an audit on the eve of Christmas, George panics and contemplates suicide, but not before he has implored God for help. Clarence (Henry Travers), a sort of B-rated angel who hasn't yet earned his wings, is accordingly despatched from on high to help. In his misery, George feels it would have been better if he'd never been born, but Clarence points out what a different place Bedford Falls would have been without George, reminding him of all the people he has helped and all the good he has done without expecting thanks.

Clarence then rallies the citizens of Bedford Falls, who chip in to cover the missing money. Directed by the great Frank Capra, It’s a Wonderful Life is a tale of almost Dickensian density: George, brilliantly played by Stewart, is an honest everyday person facing a corrupt system who also asks for help from God, not knowing what to expect.

Clarence is hardly the Angel Gabriel, but in a way that's part of the film's charm: his everyday-ness fits perfectly into a movie that brings a powerful sense of post-war America’s ideals and struggles to the screen, demonstrating the importance of faith in a fallen world.

A Charlie Brown Christmas (1965), written by Charles M. Schulz and directed by Bill Melendez, might seem an odd choice for a festive round-up, but Charlie Brown’s creator Schulz was a devout Christian determined that a half-hour-long Peanuts-based Christmas special should get the season’s true message across in an industry worried that religion was a controversial topic, especially on television. When Melendez mentioned this to Schulz, he replied: “If we don’t do it, who will?”

When the characters go to the tree lot to pick out a tree for their show, Charlie Brown picks the only real tree there, a small and rather hopeless-looking sapling. Linus wonders whether this is the right choice, but Charlie Brown believes that once decorated the tree will be perfect.

His friends, including Lucy, scorn him and walk away laughing. Charlie Brown then asks if anyone knows what Christmas is all about. Linus pipes up that he does, asks for a spotlight and, dropping his precious security blanket, proceeds to recite the King James Version of the annunciation to the shepherds, as described in verses 8–20 of the second chapter of the Gospel of Luke. When he has finished, he picks up his blanket and says, “That’s what Christmas is all about, Charlie Brown.”

This Christmas special was commissioned by the mighty Coca-Cola Company and produced on a relatively tiny budget in just six months. Everything about the production was a gamble, including the use of child actors’ voices and the unorthodox jazz score by pianist Vince Guaraldi.

They needn't have worried. The show was an immediate hit and has become, rightly, a seasonal classic.

The Bishop’s Wife (1947) is a Christmas fantasy rom-com with a supernatural element, supposedly set in New York. It has a stellar cast with David Niven as the Episcopal bishop Henry Brougham, Cary Grant as the very debonair angel, rather improbably named Dudley, Loretta Young as the bishop’s glamorous wife Julia, and Elsa Lanchester as the Broughams’ housekeeper.

Henry Brougham has been toiling for months on the plans for an elaborate new cathedral which he hopes will be paid for primarily by a rich but rather difficult widow, Agnes Hamilton, played by Gladys Cooper: Henry is losing sight of his family and of why he became a clergyman in the first place. Enter Dudley, whose mission is to help all of the characters find their way through their troubles, just not necessarily in the way they expect.

Henry wants funding from his parishioner and Agnes does eventually offer money – just not for the new building but instead for the poor and needy. Julia confides her marital problems to Dudley who in turn finds himself becoming attracted to her. When Henry realises this, he tells his atheistic friend Professor Wutheridge, who urges Henry to fight for the woman he loves.

On several occasions throughout the film, Dudley is shown to have special powers, but when he hints to Julia his desire to stay with her and not move on to his next assignment, Julia tells him it is time for him to leave. When Henry demands to know why his cathedral plans were derailed, Dudley reminds him that he had prayed for guidance, not for a specific thing.

Realising that Julia loves her husband, Dudley departs, and all memories of him are erased. Initially, the film performed poorly in theatres because movie-goers were put off by the film’s religious connotations, so the studio added a new strapline to the original poster: “Have you heard about Cary and the bishop’s wife?” Business duly soared by 25 per cent, such was Cary Grant’s box-office magnetism.

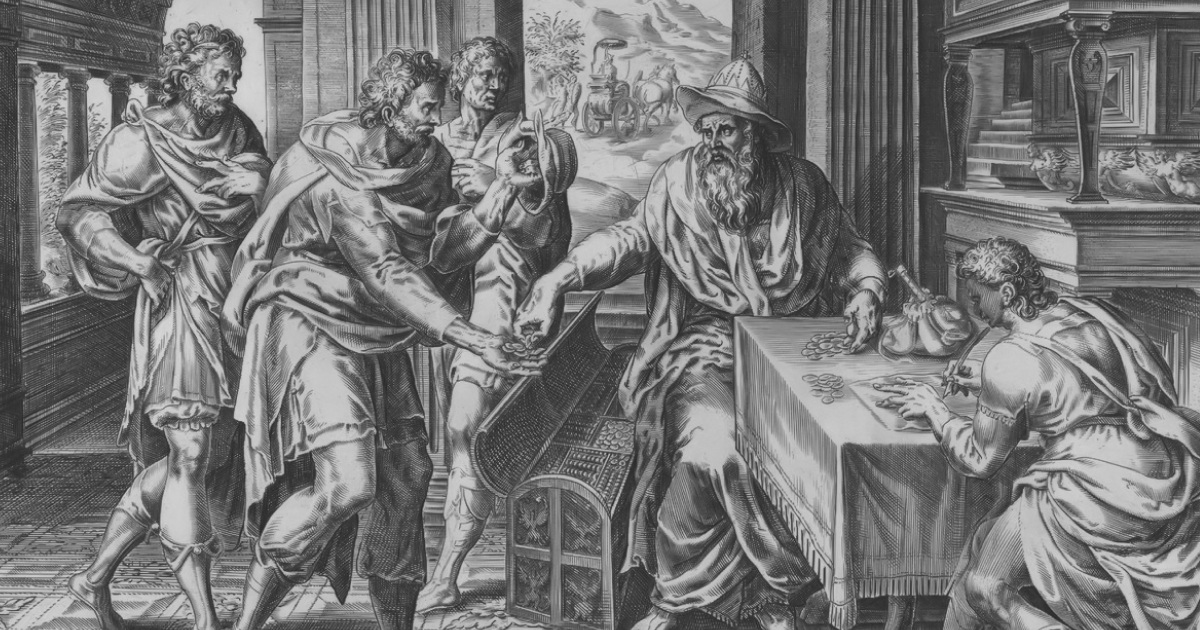

Finally, you can’t really have Christmas without mention of Scrooge in A Christmas Carol. One of the greatest Scrooges of all time has to be Alastair Sim in the 1951 adaptation of Dickens’ novel, directed by Brian Desmond Hurst and originally titled Scrooge.

There have been several excellent versions of this Dickens fable about a raging miser who becomes the embodiment of the spirit of Christmas following three spectral visions. But it’s this version that has become the classic, most of which is due to Sim’s unforgettable performance as Scrooge, with Jacob Marley, the ghost who changes Scrooge from sinner to saint, played by Michael Hordern. “Hard and sharp as flint he was,” says the narrator’s voice quoting from the text, as Scrooge berates Bob Cratchit (Mervyn Johns) when he asks Scrooge for more time to repay a debt at the beginning of the film. Mrs Cratchit is played by Hermione Baddeley, and pathetic but valiant Tiny Tim by Glyn Dearman.

Sim revisited the character of Ebenezer Scrooge in the 1971 Oscar-winning animation of A Christmas Carol, but for me it’s the 1951 version which has my heart and is the Christmas film I return to most often.