At a primary school in Inverness this year, the Nativity has been cancelled after ‘racist and abusive messages’ were sent to staff. What could prompt such hate and vitriol? The story of Jesus’s birth in Bethlehem transcends political divides and has unified the masses for millennia. Right?

Well, therein lies the difference. This was not the Nativity. It was a ‘modern retelling’ of the story which featured Santa’s helpers at the North Pole, refugee children in the Syrian conflict, and even a musical number about the struggle of crossing the border.

It need hardly be said that abusing school staff is not an appropriate form of protest. Some messages were directed at children. Racism is never acceptable. The fault lies with the senders. Yet the source material is an issue we ought to examine more closely, because although enraged locals took the wrong route to voice their concerns, we must fight the secularisation of Christ’s holy birth.

Across the United Kingdom, well-intentioned headteachers quietly rebrand Christmas as a ‘winter celebration’. Some still allow a performance but rewrite the script. In recent years we have seen Mary retained but Joseph removed because fatherhood language might be a sensitive subject. We have seen shepherds become farm helpers, angels become winter messengers, and the baby in the crib described only as ‘a child’. One London school replaced the nativity play with a story about a lost reindeer because it was, in the words of the head, ‘safer for everyone’.

In another school, parents were told their children could still wear costumes, but would no longer speak religious lines. The reception class still paraded across the school hall in cardboard crowns and dressing gowns, although the reason those costumes existed at all had been removed, leaving pupils without a clue of the story’s holy origins.

What is offered as neutrality is erasure. The Nativity story is treated as a problem to be solved, not a tradition to be respected. Other religions’ tales and traditions are invited into schools as living cultures, while Chrisitanity is treated as softened heritage, stripped of claim and content.

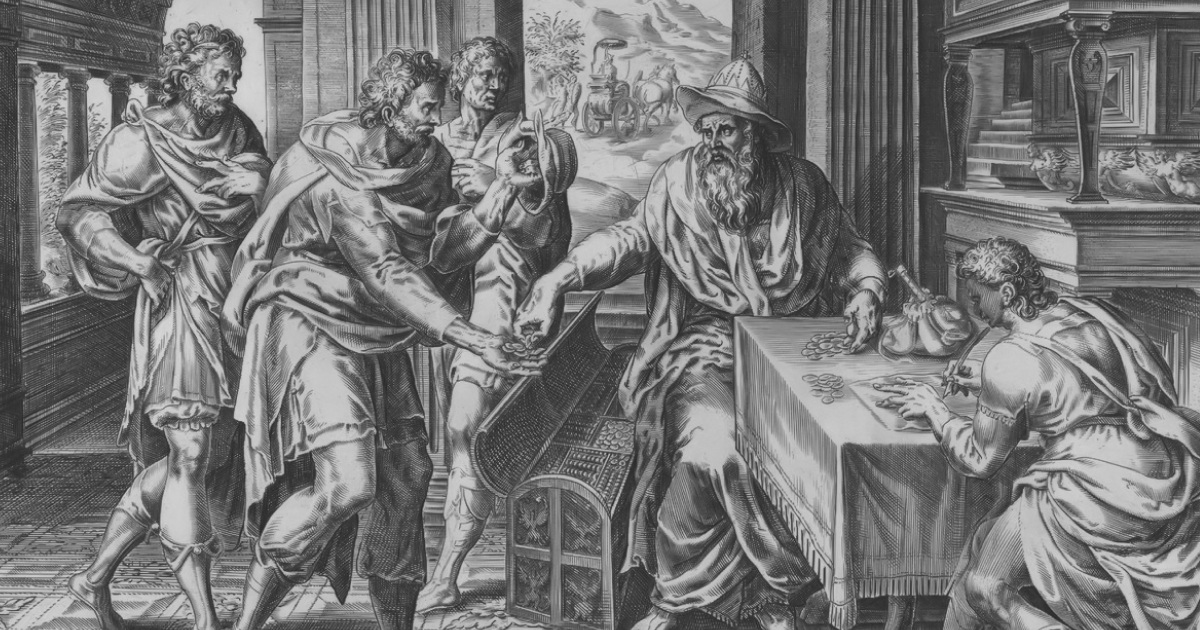

The odd thing is that the nativity itself remains a story which encapsulated the inclusive themes schools are purporting to uphold. It begins with a forced journey under government order, a birth far from home, a family without security. It ends in flight from political violence threatened by Herod. In the very year a school sought to support refugee children, it removed the one story in the calendar that most closely mirrors their experience.

The reasoning is always the same. Someone might be offended. Someone might feel excluded. But it is rarely made clear who this ‘someone’ is. Parents are rarely consulted. Children almost never object. Churches are not asked for advice or expertise, unlike other religions where synagogues, gurdwaras, and mosques are often consulted on educational efforts.

The result is the Nativity is diluted in advance. A story of God made man becomes a vague sketch of diversity and tolerance. Pupils are told to sing about light without being allowed to say what the light is. They rehearse a festival without being taught why it exists. The assumption is that children from non-Christian backgrounds cannot cope with Christianity in a public institution, while Christian children are expected to accept other religions’ festivals, and the disappearance of their own, without remark.

This is not equal treatment. It is a double standard so familiar it now passes without comment.

The deeper loss is not theatrical but formative. The Nativity once taught children that human worth does not come from status or strength. It taught that God enters the world without power, force, or display. Remove this and Christmas becomes a season of mood without a message. It becomes atmosphere without claim.

What schools now offer instead is usually well meant but thin: assemblies about being kind, songs about sparkle and winter, posters about sharing. In the case of the school in question, calm was sought by removing the festival, not by confronting the moral failure of doctoring a holy Christian story.

A society that cannot bear to let its children stand in a line and speak simple words about a birth in Bethlehem is not progressive but timid. The model set is not neutral. It quietly teaches children a dangerous lesson, whether adults intend it or not: that the oldest story in the room is the first to be discarded when things grow difficult, that disagreement is managed through subtraction, not explanation, and that peace must be preserved, even at the cost of sacred origin and tradition.

Britain remains a Christian nation and children do not need protecting from the Nativity. The Nativity needs protecting from adults embarrassed by its origin, and by Christianity itself.