In the pantheon of improbable historical figures, Nicholas Breakspear, later known as Pope Adrian IV, stands as a quirk of providence. The only Englishman ever to ascend the Chair of St Peter was not a Norman nobleman or Plantagenet prince but the son of a lowly Hertfordshire clerk.

His election was not merely an ink blot on the parchment of Catholic history, but a subtle acknowledgement that the papacy was no longer the preserve of the Mediterranean dynasties; that Christendom could reach beyond the predictable confines of Rome, France or Spain. In drawing leadership from the misty moors of England, the Church acknowledged for the first time that its half-barbarian outposts, once reduced to missionary territories, were gaining purchase and influence.

Adrian’s reign itself was brief and fiery. He inherited a Church embattled with the Roman commune, led by reformist Arnold of Brescia, who had dared to denounce clerical luxury and stir citizens to consider a senate sans pope. Determined not to be reduced to a powerless figurehead bishop in a toga republic, the Englishman did what popes of the age did best: he excommunicated his enemy. Arnold was soon captured, handed over to imperial forces, and publicly burned in a spectacular (if brutal) assertion of papal authority — a neat reminder that “cancel culture” existed long before the bitter battlegrounds of social media.

Adrian’s ambitions were not confined to central Europe. In 1155 he issued the Laudabiliter, granting Henry II dominion over Ireland. Whether the document was genuine, interpolated or a later forgery remains disputed, but its political impact was immense. With a few strokes of the papal pen, Adrian entangled the papacy in the birth pangs of English imperialism and laid the foundation for centuries of Irish grievance.

Pope Adrian’s impact on his home turf was especially transformative: England’s only pope effectively wrote the recipe for its future colonial crusades. His was the twelfth-century papacy in its rawest form — part spiritual monarchy, part geopolitical broker, part meddlesome land agent. Adrian IV was no visionary reformer like Gregory VII, nor a philosopher pope in the mould of Innocent III, but a pragmatist who wielded power as circumstance demanded.

But what does a common-stock clergyman from Abbots Langley have to do with twenty-first-century North America? Namely, that Rome’s gaze has once again wandered west to its English-speaking corners.

Pope Leo was as unlikely a papal candidate as Breakspear: neither the bookies’ favourite nor blessed with the kind of reputational stature to compete in the court of public opinion — least of all when names like the Philippines’ Luis Antonio Tagle, the conservative warhorse Robert Sarah, or Italy’s Zuppi and Parolin were being confidently muttered by Vatican watchers from the outset.

But this is where the parallel ends. Adrian IV was a curiosity, a foreign pontiff chosen precisely because his homeland posed no threat to Rome. England in the twelfth century was a damp provincial outlier, not yet a hegemon bestriding the globe. We were still licking our wounds from civil war; our kings were more concerned with corralling barons than commanding emperors.

America, by contrast, has been a global juggernaut since its inception. A papacy stamped with “Made in the USA” was long seen as a non-starter, not because the United States lacked political relevance, but because the scales were already so unbalanced in Uncle Sam’s favour. Its reach is measured not only in armies but in the soft power of Hollywood, Silicon Valley and Wall Street. To add the papacy to that arsenal would look less like providence and more like annexation — Christendom absorbed into the Pax Americana.

Yet here we are: a Westerner on the throne of St Peter, and the future of Catholicism preached with a decidedly Midwestern twang. For all the anxieties about American hegemony, it feels as if a Pope Leo might be precisely what we need.

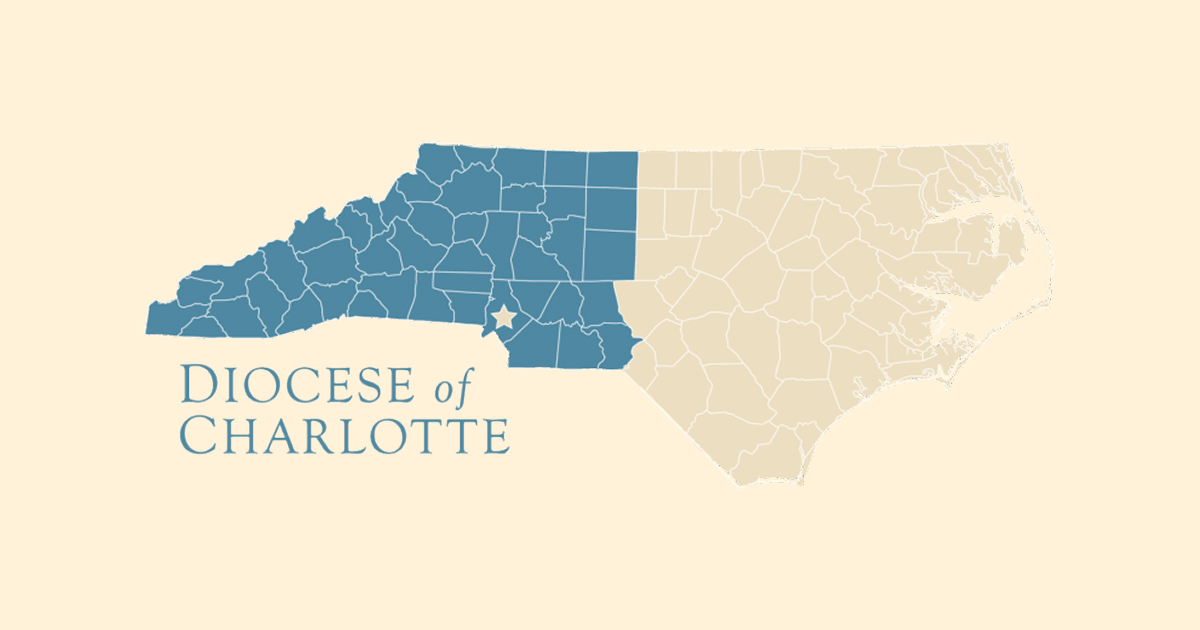

His obscurity, which made him an unlikely candidate in the first place, might prove an advantage: he is not entangled in the rivalries of the Italian curia, nor burdened with the celebrity expectations that dogged Francis. Moreover, Leo’s pastoral record in North America is appealing to a Church still wrestling with its fractured history and scandals. He governed a diocese bruised by abuse allegations, financial crises and emptying pews — and did not shirk the mess as many of his colleagues did.

He slimmed bloated chancery offices, published the accounts, and even won the tentative respect of secular journalists in his home turf. A global celebrity he isn’t, but his credentials stand him in better stead than a million Instagram followers or a flashy résumé in Rome.

Theologically, Leo has been more schoolman than showman, emphasising the importance of social teaching and the need to live by doctrine rather than merely preaching it. The duty of the modern Catholic is to stand against the winds of moral decay, and it is refreshing to hear a religious leader speak of the dangers of following trends. He is not a culture warrior like Robert Sarah, but neither is he inclined to dilute doctrine for applause like certain Anglican leaders (I’m looking at you, Justin Welby).

He cannot escape being read by conspiracy theorists as an extension of American power, just as John Paul II was viewed through the prism of Cold War Poland. But the Church has benefited from such gambles before.

John Paul’s Polish origins were a Cold War masterstroke, destabilising the Soviet bloc in ways the CIA could only dream of. His presence in Rome emboldened the Allied powers, and his sermons did more to crack the veneer of communism than any Washington war room.

Now America finds itself in a similar internal crisis. Biden’s twilight presidency was marked less by grand strategy than by managing civil disorder and questions of competence. The Trump years, meanwhile, introduced a style of politics that seems in permanent campaign mode. Add a tinderbox of social arguments: abortion re-litigated in the Supreme Court, gay marriage and gender ideology contested at all levels, and race relations reduced to a game of victimhood monopoly.

Despite its wealth and power, America is spiritually impoverished — a Goliath stumbling through moral darkness with its pockets full of gold. And it is in solving this problem that having an American pope will matter most.

Adrian IV was the unlikely Englishman who laid the Church’s global roadmap, and it follows that Leo may well be the unassuming North American who steers Western Catholicism back on course.

.jpg)