For me and, I imagine, for my contemporaries, the story we learn of Jesus’s birth is the story related by the school nativity play.

The angel Gabriel appears to Mary and tells her she is to have a baby who will be Christ, the Lord. She and Joseph (who is lucky if he gets more than two lines in the whole thing) go to Bethlehem on a donkey, find no room at the inn but are permitted to bed down in a stable, where they have the baby and lay him in a manger. Shepherds and three kings visit in quick succession, and we all sing “Away in a Manger”. The end. It will not surprise the reader to learn that this story appears in none of the Gospels.

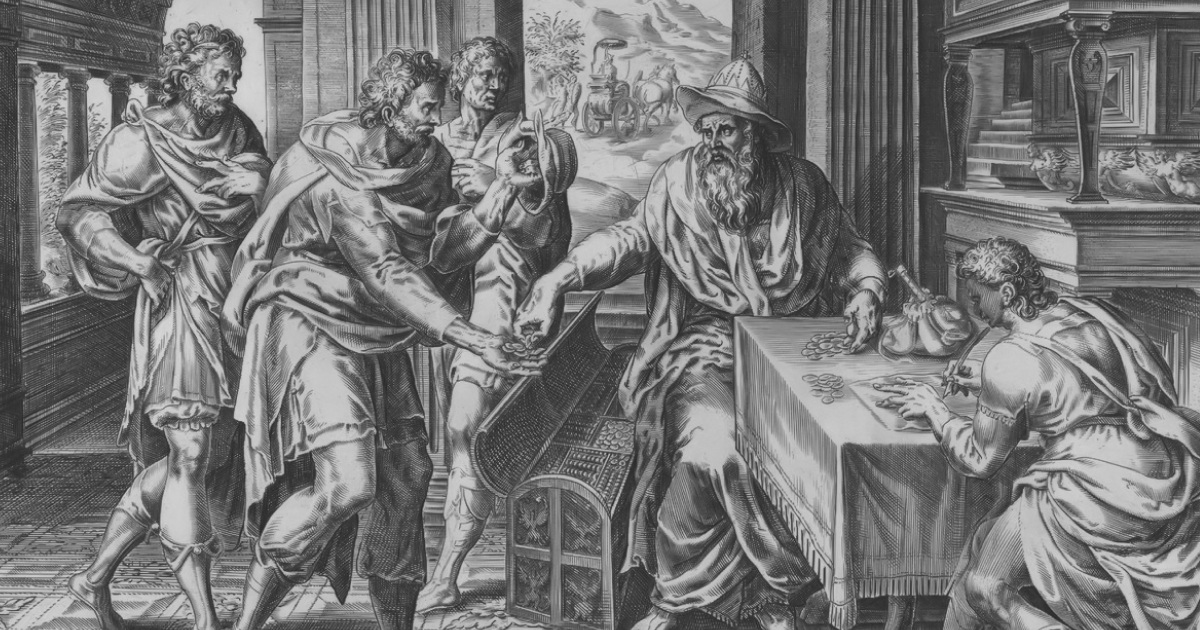

But it is perhaps less well known that while St Matthew does have an annunciation scene, it is to Joseph rather than to Mary. It is no exaggeration to say that Joseph is far more important than his betrothed in the first two chapters of Matthew: he is the one told of the coming birth by an angel (albeit in a dream), he is the one whose ancestry is given at the beginning of the Gospel, who names Jesus, and who orchestrates the flight into Egypt after the visit from the wise men. These, the reader will already know, are not kings and are not said to be three in number.

On the other hand, St Matthew has no shepherds, no presentation in the temple, nothing about the parallel birth of John the Baptist or the Visitation. St Luke has nothing about the wise men, their meeting with Herod and the subsequent massacre of the Holy Innocents. Now one of the key questions in the study of the Gospels is whether Matthew and Luke knew each other’s work. The majority view is that they did not: the substantial areas of overlap in their Gospels which they did not both get from Mark is often put down to a now-lost shared source that scholars label “Q”. If this is so, then obviously it is not a problem that they lack features of each other’s infancy narratives. Most would agree that Q was a collection of sayings of Jesus, and did not have anything about his childhood at all. But then we have the interesting question of why there is some overlap in their infancy stories: why do both agree that Jesus was born in Bethlehem, even though he was brought up in Nazareth?

Why do both agree that Jesus was not the natural son of Joseph? These are both points that sceptical historical-critical biblical scholars suspect are unhistorical, and yet on the mainstream scholarly view they have been fabricated independently by two different Gospel writers.

A view more prevalent in the UK than elsewhere, though, is that St Luke did have Matthew’s Gospel to work with as well as Mark’s. If this is so, then different problems emerge: firstly, what was the other source that he used for his non-Matthean material? To my mind, this is easily solved: he visited and questioned the mother of Jesus in her old age. He was, after all, a committed research historian, as he himself insists at the beginning of his Gospel. The more serious difficulty is why he omits the tale of the wise men, their visit to Herod and the subsequent massacre of the innocents. This last, in particular, is broadly doubted by historical critics since it is not mentioned in any other sources though as I have argued before, I don’t think this is such a serious problem — how many infants were there “in and around Bethlehem”? It’s a tiny place, so perhaps a dozen or so. Sadly, the killing of even a large handful of babies at that time and place might not have made much of an impact in the wider world.

The greatest difficulty, though, is that one would have thought St Luke would have liked

the story of the visit of the Magi. It would fit in well with his theme of Christ as the light for revelation to the Gentiles, to quote the prophet Simeon. However, when one examines it carefully, one sees that St Luke’s infancy narrative is a carefully structured one — historical, yes, but also stylised in its presentation, and perhaps this Matthean tale could not be neatly incorporated. Moreover, if he was writing not to replace but to supplement Matthew, then he was not obscuring a tale already known to his readers. The nativities of Christ certainly present some interesting and puzzling features, and will repay careful attention in this season.

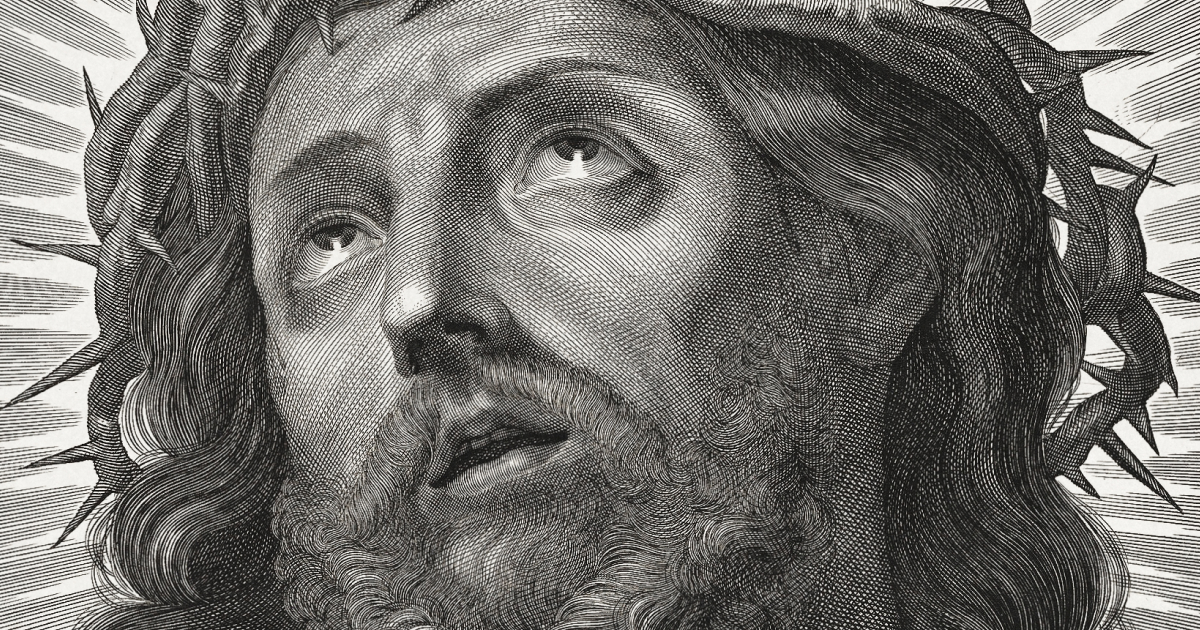

But this careful attention need not cause anyone — unless they have already decided not to believe in any of it — to doubt that the Christmas story is true.