If you draw the history of Catholic–Orthodox relations as a family tree, you end up with a rather tangled shrub: shared roots, several dramatic quarrels, and an awkward silence that lasted, in some cases, for a millennium and a half. Yet in that thicket there are also clearings of real friendship. One of the most instructive is the relationship enjoyed between Pope Benedict XVI and Pope Shenouda III of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, a case study in how old wounds can be named, healed and, at least partially, transformed into a common witness.

What follows is a Catholic reading of that story: why we were divided, how modern dialogue has changed the landscape, and what Benedict and Shenouda managed to achieve together, especially for relations with the wider family of Orthodox Churches.

But first, how did we get here? When Catholics say “Orthodox”, we usually mean two overlapping but distinct families. First, the Eastern Orthodox Churches (Constantinople, Moscow, etc.), whose formal break with Rome is usually dated to 1054, though the estrangement was a long, slow burn. Second, the Oriental Orthodox Churches (Coptic, Syriac, Armenian, Ethiopian, Eritrean, Malankara), who separated much earlier, after the Council of Chalcedon in 451.

The Coptic Orthodox Church belongs to this second group. For centuries Latin and Greek theologians labelled them “Monophysites”, accusing them of collapsing Christ’s humanity into His divinity. The Copts, for their part, saw Chalcedon as a betrayal of the Cyrilline insistence on the unity of Christ’s person.

It is now one of the quiet triumphs of twentieth century theology that both sides gradually realised they had been talking past each other. Careful historical work showed that the Copts’ miaphysite formula (“one incarnate nature of the Word of God”) was not Eutyches’ heresy but a different way of safeguarding the same mystery: Christ is fully God and fully man, united in one Person.

That recognition paved the way for what may be one of the most important, and least read, ecumenical texts of the last century: the Common Declaration signed in Rome on 10 May 1973 by Pope Paul VI and Pope Shenouda III. There, the Bishop of Rome and the Pope of Alexandria jointly confessed Christ as “perfect God with respect to his divinity, perfect man with respect to his humanity”, explicitly condemned both Nestorius and Eutyches, and acknowledged that many of their historical quarrels were due more to “differences of terminology and of culture” than to faith itself.

The 1973 declaration also established a joint commission. That little seed would later grow into the International Joint Commission for Theological Dialogue between the Catholic Church and the Oriental Orthodox Churches, formally launched in 2003.

So, by the time Joseph Ratzinger became Benedict XVI in 2005, he inherited not a blank slate but an ongoing theological conversation, one that had already cleared the central Christological hurdle which had divided Rome and Alexandria since the fifth century.

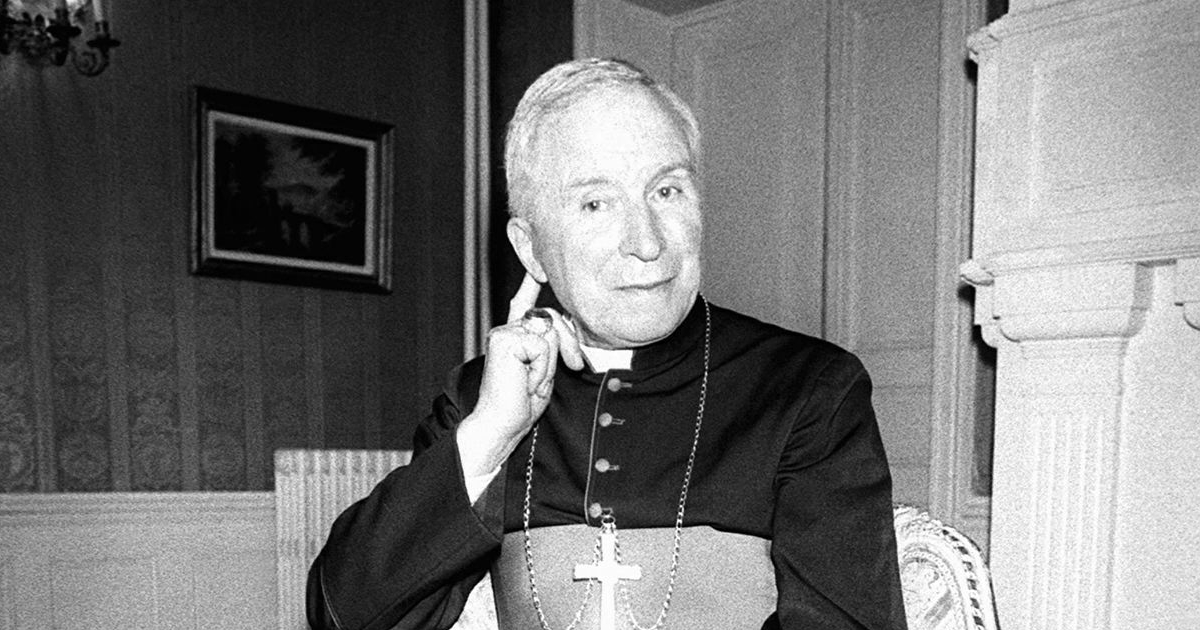

Benedict XVI is often pigeon holed as an “internal” theologian, more interested in shoring up Catholic identity than in ecumenical experiments. The historical record is less convenient. As Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, he had already helped shape the Catholic Church’s approach to Eastern Christianity after Vatican II, insisting that unity could not be bought at the price of truth, but also that many ancient anathemas no longer applied once terms were clarified.

As Pope, he pursued what he himself called an “ecumenism of truth and charity”: patient doctrinal work combined with very concrete gestures. With the Eastern Orthodox Churches, this meant, among other things, the 2007 Ravenna document on primacy and synodality, the first joint text in which Catholic and Orthodox theologians together affirmed that a universal primacy existed in the undivided Church, even if they still disagreed on how it should function today.

With the Oriental Orthodox, and the Copts in particular, Benedict built directly on the Paul VI–Shenouda foundation. He repeatedly praised the 1973 Common Declaration as a model of how ancient Christological disputes could be resolved without anyone denying their own tradition. He encouraged the Joint Commission to move from Christology to ecclesiology, the thornier question of how authority, synods and primacy should work if communion is to be restored. The Commission’s 2009 document, “Nature, Constitution and Mission of the Church”, is one fruit of that effort.

Benedict also understood that ecumenism does not float above history, as he had also demonstrated with the Anglicans and Anglicanorum Coetibus. Egypt during his pontificate was facing rising Islamist pressure on Christian communities. Copts were living, quite literally, under fire. Benedict used his addresses and messages to Coptic delegations to link theological dialogue with the shared task of witnessing to Christ under persecution. When Shenouda III died in 2012, Benedict’s telegram saluted him as a “courageous witness of Christian faith” and recalled with gratitude the 1973 declaration as a “milestone” on the common path.

In other words, Benedict’s approach to the Copts was neither romantic nor merely diplomatic. It was a classic Ratzinger synthesis: dogmatic clarity, historical realism, and a quiet personal esteem for a fellow patriarch who had held his Church together through difficult decades.

If Benedict brought the Bavarian theological encyclopaedia to the table, Shenouda III brought something equally formidable: the desert.

Formed by the Coptic monastic tradition, Shenouda was at once a scholar, a preacher, a prison chaplain and, not least, a survivor of repeated confrontations with Egyptian governments. Under President Sadat he was even confined to a monastery for several years. His long patriarchate (1971–2012) saw both a dramatic growth of the Coptic diaspora and an escalation of local violence against Christians.

It is not hard to see why Rome valued a partner like this. Shenouda represented a Church that had never been part of the Byzantine Empire, never undergone the Reformation, and never accepted Chalcedon, and yet whose faith in Christ was recognisably, robustly orthodox in the small o sense. When Paul VI embraced him in 1973, it was not a public relations stunt; it was a recognition that the Church’s ancient Alexandrian memory could not simply be written off as a fifth century mistake.

The joint Catholic–Coptic commission that grew out of that meeting met intermittently over the following decades, producing agreed statements on Christology and sacraments and exploring practical questions such as mixed marriages and pastoral collaboration in the diaspora. During Benedict’s pontificate, those conversations were folded into the wider Joint Commission with all the Oriental Orthodox Churches. That move both broadened the dialogue and, in a sense, vindicated Shenouda’s persistent insistence that the Copts were not a marginal sect but an integral part of the wider Eastern Christian story.

For Catholics, the Benedict–Shenouda relationship offers an important lesson in style as well as substance. Neither man was given to sentimental ecumenical photo opportunities. Both had reputations for intellectual rigour, occasionally even stubbornness. Yet precisely these two managed to consolidate a relationship of trust that now serves as a reference point for their successors.

It would be comforting to end the story with a steady upward line: the 1973 declaration, the joint commission, Benedict’s encouragement, and then happily ever after. Reality, of course, is messier. Ecumenical progress is not a straight line but a sort of theological ECG: advances, pauses, and the occasional alarming dip.

Recent years have brought new tensions. The very Joint Commission Benedict supported has had to navigate disagreements over proselytism, ecclesial identity and, more recently, responses to contemporary moral questions. Matters came to a head in 2024, when the Holy Synod of the Coptic Orthodox Church announced the suspension of its participation in official dialogue with the Catholic Church. The reason, stated openly, was the publication of Fiducia Supplicans, a document authorising certain forms of non liturgical pastoral blessings, including for persons in same sex unions. Publicly, Fiducia Supplicans was presented by the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith as a pastoral, non doctrinal clarification meant to distinguish between liturgical rites (which remain unchanged) and spontaneous blessings offered to individuals seeking God’s help. For Pope Francis, the document expresses a signature theme of his pontificate: that the Church’s first gesture must be one of mercy, and that pastoral closeness need not imply doctrinal change.

For many in the Coptic Orthodox Church, however, the document was interpreted as a de facto shift in moral teaching, or at least as an ambiguity too great to ignore. Their response does not cancel 1973, nor does it erase the profound respect Benedict XVI and Shenouda III showed one another. But it is a sobering reminder that trust, once gained, must be continually tended. Ecumenism is not only about theology; it is also about the perception of stability, clarity and mutual reliability.

What, then, might a Catholic future for Catholic–Orthodox, and specifically Catholic–Coptic, dialogue look like? A few elements suggest themselves.

First, guard the Christological gains. The clarity reached about Christ’s person and natures in the 1973 Common Declaration, and in subsequent joint statements, is not a negotiable “nice to have”. It is the dogmatic foundation on which everything else rests. Whatever new controversies arise, Catholics and Copts now officially recognise that they confess the same Lord, not different Christs in rival metaphysical outfits. That achievement should be taught in seminaries, catechesis and popular apologetics more widely than it is.

Second, let ecclesiology mature slowly. Questions of primacy, synodality and the concrete exercise of authority are both crucial and delicate. Benedict was under no illusions here. His own writings on papal primacy are frank about both the need for the Petrine ministry and the ways in which it can be lived more “synodally” in the future. With the Oriental Orthodox, the challenge is slightly different from that with Constantinople and Moscow, but the logic is the same: communion cannot mean absorption. If unity is ever restored, it will have to be a unity that honours the real, apostolic traditions of Alexandria and the other Oriental sees.

Third, bind doctrine to martyrdom. Benedict often linked ecumenism with the “ecumenism of the martyrs”: the fact that persecutors do not care whether a Christian is Catholic, Coptic or Protestant before they burn a church or bomb a bus. The blood of contemporary martyrs, he argued, has its own quiet voice calling for unity. Egypt’s Copts, who have buried more than enough martyrs in recent decades, know this in their bones. A Catholic ecumenism that forgets this lived witness in favour of purely academic conferences would be badly disordered.

Fourth, keep a sense of humour and proportion. Compared with the mysteries at stake, many of the cultural irritations between East and West are surprisingly small: calendars, beards, liturgical choreography, and the question of whether the Holy Spirit prefers to proceed “from the Father” or “from the Father and the Son” when Greeks and Latins are arguing. None of this is trivial. Doctrine and worship matter deeply. But Benedict and Shenouda, each in his own way, managed to distinguish between what is of the esse of the faith and what is of the bene esse, between what is non negotiable and what is simply a beloved habit.

Catholic–Orthodox dialogue, especially with the ancient Coptic Church, may be healed by exactly the virtues that Benedict XVI and Shenouda III displayed: theological seriousness, historical honesty, personal friendship, and a willingness to let God work more slowly than our press releases would like.

The good news is that the most difficult theological work, at least on Christology, has already been done, and done together. The challenge now is to live as though that were true, on both sides of the Mediterranean, and to let that shared confession gradually seep into the structures, habits and instincts of ecclesial life.